With the re-opening of a 520-seat theatre in Srinagar, Kashmir has revived an entertainment window that existed since 1932. The closure of the cinemas was a major infrastructure deficit. While the screen was in hibernation, the people, not only created their own means to watch Bollywood and Hollywood even at the peak of turmoil but also made acting a career choice, reports Masood Hussain

The re-opening of the erstwhile Broadway Cinema has been a major event in recent days. Almost every media outlet of any significance across the globe ensured the event is adequately covered.

Jammu and Kashmir administration encouraged Inox Leisure, India’s premiere movie theatre chain to open cinemas in Kashmir. While in the districts, it would spend Rs 30 lakh to set up small careens, the major one was thrown open in Srinagar by Lt Governor, Manoj Sinha last week. It has 520 seats and three screens. The premises owner, Vijay Dhar, tied up with Inox and the cinema will operate normally in early October.

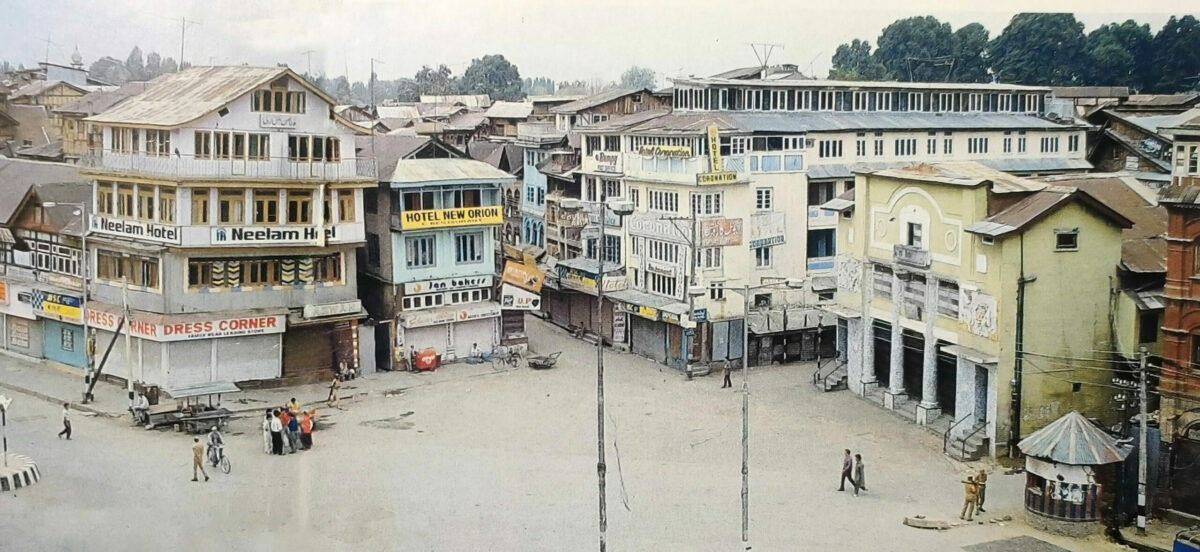

Cinema is a key infrastructure that was impacted by the turmoil of 1989 summer. A group of insurgents banned the operations of the cinemas – along with liquor, by the yearend. Almost locked for a year, these huge premises quickly got converted into garrisons or were abandoned to rot. Srinagar city alone had eight cinemas. Khayam was converted into Khyber, a major super-speciality hospital in Srinagar. Regal, one of the oldest, is an emerging mall. Shah Cinema, Firdous, Naaz, and Shiraz are housing the paramilitary forces. Neelam is closed but intact and the oldest one, the Palladium is in ruins and also is partly housing the CRPF. It is Broadway which is now operational and run by Inox.

There were two cinemas hall each in Anantnag (Heewan and Nishaat), in Sopore (Kapra and Samad Talkies) and one each in Baramulla (Regina), Handwara (Heemal) and Kupwara (Marazi) as Army was running a cinema hall each in Srinagar, Baramulla (Thamaya) and Pattan (Zorawar). Barring the ones operated by the armed forces, all others were either abandoned or simply witnessed a change in the use of the space. The shutting of the doors was quickly felt as the people manning these huge facilities were literally on the roads. Many families broke and a few died under debts and uncertainty.

Evolution of Cinema

“The cinema in Kashmir is essentially the story of the Palladium Talkies started in 1932 by Bhai Anant Singh Gauri,” author and former officer, Khalid Bashir Ahmad wrote in his long piece on the evolution of Kashmir’s entertainment sector. It was the same family that donated over 50 kanals of land to the Sher-i-Kashmir Institute of Medical Sciences (SKIMS) Srinagar in 1978mna that is the reason why the Institute’s Ward No 4 (urology) is named after him. “Bhai Anant Singh’s grandson, Manmohan Singh Gauri claims that the Palladium Cinema was the oldest movie hall in north India and would screen Hollywood movies before these were released in Delhi which did not have a good market for English films then.”

It was the great-grandfather of fashion designer, Rohit Bal, that set up the Regal. The family also owned a screen each at Gulmarg and Lahore. Khalid has referred to the yearly administrative report of the Maharaja government of 1940–41 that mentions “one (cinema) caters chiefly for Europeans and educated Indians and the other provides amusement chiefly to Indian audiences.” It had the pre-partition tradition of running Hollywood films. Watching the success of the two cinema halls, another Punjabi family applied for permission but it was resisted by people. On November 30, 1935, the newspaper Martand commented: “a third cinema hall will reduce to extremity a people already depleted of their resources by the existing cinema halls”.

In the next decade, Bal’s added another cinema hall to Regal and called it Amresh Talkies. Post-partition, both halls were taken over by Bakhshi Rashid, the powerful brother of Bakhshi Ghulam Mohammad. Later, a cinema was opened in Anatnatng, Baramulla and Sopore. Gradually the numbers improved. By 1990 all were locked. Given the popularity, these cinemas continue are still landmarks – Regal and Palladium but Kashmir still has Regal Chowk and Palladium Gali.

Kashmir’s Screen Story

1932: Capitalist Bhai Anant Singh Gauri started Palladium Talkies by showing Alam Ara. The cinema premises became a public space in 1947-48 and most of the speeches Pandit Nehru made were there. It was destroyed in a major fire incident in 1993. It could not be rebuilt owing to a dispute over the lease.

1933: Influential Bal family started Regal. They later had a cinema each in Gulmarg and Lahore. Mostly showing Hollywood films, its dilapidated wooden building collapsed in the 1970s.

1940: Bal family was permitted to start Amresh near the Regal. In 1950, the ownership of two Bal-owned theatres was taken over by Bakhshi Abdul Majid. During the Holy Relic agitation, people set afire to both the cinemas on December 28, 1963. Later, the government permitted the reconstruction of only Regal with 1340 seats and it re-opened in 1967.

1945: Influential Bhai Anant Singh Gauri, a Punjabi-speaking family of Srinagar, started Regina Cinema, on Maulana Azad Road. A year later, they launched Jai Hind Talkies in 1946. It operated in Suthra Shahi. Post-partition, the government acquired Jai Hind Talkies and converted it into coal storage. Later, it was auctioned and purchased by Khawaja Saifuddin, who started it as Neelam Cinema in 1966. The government also took over Regina and converted it into the SRTC office.

1955: Samad Talkies in Sopore was started by the richest man in the town, Khawaja Samad Pandith.

1956: Regina Cinema in Baramulla and Nishat Talkies in Anantnag start operations.

1964: Shiraz Cinema was inaugurated at Khanyar, in the interior of the city. It is a garrison now.

1965: Tirath Ambla and Dhar’s family started the Broadway Theatre in May, then the modern one. After closure in 1990, it was re-opened twice.

1968: Khayyam, the second cinema in the old city started on December 2, 1968. It was the first hall to have a 70 mm screen. It is now called Khyber Hospital.

1969: Two more cinemas come up – Naz Cinema near Iqbal Park and Firdous Cinema at Hawal. Both are garrisons.

1983: Shah Cinema was inaugurated at Qamarwari in October. It is with CRPF.

1985: A brand new Heevan Cinema started in Anantnag. The town had no such facility since 1982 when the Nisaht Talkies was destroyed in a major fire while screening the Hindi movie Surakhsha.

(Compiled on basis of the research of Khalid Bashir Ahmad)

Multiple Relations

Cinema being a powerful tool of communication, Kashmir took its own time to establish the relationship as it exists in slivers. For most of the time, the cinema was the only window of “amusement”, as an official report of 1940 suggests. It took a bit of time for the audience to understand the message. “When Khana-e-Khuda, a film based on the annual Islamic pilgrimage of Haj, was screened in the Shiraz in 1968 the entire cinema hall was first washed to give it a holy ambience,” Khalid wrote. “Many people who came to watch the movie removed their footwear in reverence before entering the cinema hall.” It reached the next level when Regal showcased the Lion of Desert in 1985 summer, a film on the life of Omar al-Mokhtar. It changed Kashmir forever.

Though the entertainment sector in Kashmir once hosted the biggies from 20th Century Fox, a major Hollywood entrainment company, but Kashmir started discovering another facet of cinema soon after the partition. Within days after the tribal raiders were pushed back, Bhagwan Das Garga (1924-2011) was one of the many writers and filmmakers who responded to the call of Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah to visit Kashmir.

Balwant Gargi, his Lahore friend, accompanied Garga to Srinagar and approached Sheikh for help to make a documentary, Dileep Padgoankar wrote in the forward of The Art of Cinema: An Insider’s Journey Through 50 Years of Film History. “The Kashmiri leader told them bluntly that he had no funds for the project. All he could do was to place a houseboat at their disposal and look after the transportation,” he wrote. “With great difficulty, they managed to get a camera and raw stock which was still in short supply.”

Rajinder Singh Bedi suggested the plot envisaging a woman, Shabbo, who survived raped, her house destroyed and her husband killed. Achala Sachdev, a Delhi girl, who had never faced the camera, was given the role. The documentary, named The Storm over Kashmir by Khawaja Ahmad Abbas, was shot in real life setting in Baramulla.

Watched and appreciated by all including Pandit Nehru, Padgoankar wrote India’s Censor Board refused to pass it till it does not “show the Indian army defending Kashmir”. It also “depicted Sheikh Abdullah in a flattering light”, the censors pointed out. Even though General Thimayya helped Garga to shoot the action on frontiers, and the Censors passed it, it was never released in India formally.

However, Khalid Bashir has written that it was in 1944 when the Taj Mahal Film Company shot its film, Begum, featuring Ashok Kumar as a shepherd and Naseem alias Pari Chehra, around a short story by Sadat Hassan Mantoo. It was shot extensively in Kashmir. What was interesting was that an ‘educated Kashmiri girl’ at Weir, Chattabal showed her crossing the Jhelum with a wicker basket as a man was chasing her. Identified later as Misra, she was offered to permanently join the film line. It remains unknown if she actually accepted the offer.

It, however, marked a new relationship between Bollywood and Kashmir. Most of the Bollywood would operate from Srinagar for most of the summer. They would hire bungalows in population and take rest and make merry. Almost 100 Bollywood films were shot in Kashmir. Richard Attenborough shot part of his A Passage to India in Kashmir. It is based on EM Forster’s book that he wrote in 1912. However, the turmoil froze this relationship.

A Reluctant Return

Kashmir militancy dominated the public discourse. India’s film industry also felt a requirement to tell the story, in its own way. It was big money. Various filmmakers started getting cosy with the security grid. Mani Ratnam wanted to shoot his Roja but nobody could help. Though the story is around Kashmir, it is not shot in the Valley. It is true with all the flicks that were set in Kashmir or told a story linked with Kashmir – Kohram was shot in Kargil and Rajouri; Hero-Love Story of a Spy was shot in Himachal and Europe; Pukar was shot in Alska. Even LOC-Kargil, perhaps the longest film ever made in India, was shot in Leh and not in Kargil. It lost two of its crew members dying in high altitude sickness while shooting in Ladakh. Parts of Bjrangi Baijan were shot in Jammu and Kashmir.

It was Rattan Irani’s Mere Apne, Inder Kumar’s Mann (1999), and VV Chopra’s Mission Kashmir in 2000 that had some sequences shot in Kashmir. These films, however, set the tone. It was followed by Sheen and later by Lamhaa. After Haider was shot mostly in Kashmir including at Lal Chowk, Bollywood attempted to restore its ‘lost’ links with Kashmir. The film crews started getting more visible in Kashmir. Post-Haider, almost every war or romantic flick has something linked to Kashmir’s scenic spots.

In the last three years, there is a lot of emphasis on making Kashmir revive its age-old linkage. Now, almost every other day, the administration in Jammu and Kashmir receives an application for permission. With the administration offering more than what the filmmakers cannot even imagine in Europe in terms of hospitality and costs, almost every filmmaker is keen to be in Kashmir. Under the Film Policy, the administration intends to create a complete eco-system that suits the entertainment sector.

Not A First

With the re-opening of a major theatre in Srinagar and two smaller ones in Shopian and Pulwama, the impression generated in the media was suggested as if it was done for the first time. That may not be a complete picture.

The fact is that in 1998, the government invited the cinema owners for a long discussion following which at least three of them agreed to resume their operations if they are getting funds to revive the halls. Broadway, Regal and Neelam formally applied and were given Rs 32.50 lakh to resume their operations. For political reasons, the government wished to convey that the writ of militants has been challenged and the normality restored.

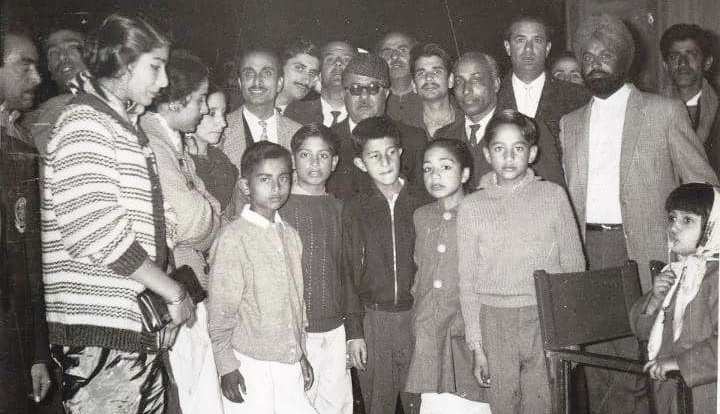

On August 6, 1998, the then Chief Minister, Dr Farooq Abdullah, joined Kashmir-born Director, Vidhu Vinod Chopra to watch Kareeb in the same cinema hall which was thrown open by Lt Governor Manoj Sinha on September 20, 2022. The fact is that small groups started going to watch movies. It did not, however, trigger the same rush as these halls used to have.

Militants were waiting for an opportunity. On September 4, 1999, a grenade was lobbed into the Regal cinema premises in the Lal Chowk area leading to the killing of one person as 20 survived with splinter injuries. The cinema was locked that very day. It was later demolished and now a tower is reconstructed on the site.

Neelam cinema reopened on April 4, 1999. Built originally in 1946 as Jai Hind Talkies by Bhai Anant Singh Gauri, the cinema was taken over by the government and converted into a coal store, according to Khalid Bashir. Later, it was auctioned and purchased by Khawaja Saifuddin Baba, a business magnate (Saifco) who re-launched it as Neelam Cinema in 1966. Post-1990s, after its re-opening, the cinema, operating under the shadow of the police and CRPF was open with a minimal audience – sometimes as less as eight – till in September 2005, an encounter broke out outside it. It led to the killing of a militant and the security grid had to make serious efforts to ensure the 70-odd people watching Aamir Khan-starrer Mangal Pandey are rescued. The curtains fell on the revival process.

Efforts to revive the screen were started in November 2019 by the CRPF when in Anantnag; they decided to revive the 525-seat Heaven Cinema wherefrom their battalion headquarters operated. They went up to Delhi and purchased a 70mm screen, speakers, and projectors, and after cleaning up the hall, put on the lights and started the show. It is known if it operates currently.

This, however, never meant that the people in Kashmir were literally Talibanised enough that they did not watch the movies, especially Bollywood. The fact is that for the worst of the turmoil decade – 1990-2002, Kashmir was watching the movies. At one point of time, the VCR was one of the major money earners in Kashmir. It would fetch a rent of Rs 200-400, per 24 hours plus Rs 25 for every film cassette. Every lane in Srinagar had at least one shop. Then cable TV took over and now satellite TV has literally converted every third home into a mini-theatre. The cell phone is actually a theatre in the pocket.

Acting as Career

The frozen cinema halls in Kashmir did not prevent the youngsters from choosing acting as a career. Kashmir right now has more actors of different status in Bollywood than there were thirty years back when the theatres were forced to shut.

Before the militancy broke out in Kashmir, Bollywood had score-odd artists from Jammu and Kashmir and most of them were Kashmiri Pandits. These included Vidhu Vinod Chopra, Anupam Kher, D K Sapru, Omkar Nath Dhar (Jeevan), and MK Raina. Post-migration, a number of new entrants to the dream city felt the tinsel town was accommodative, supportive and encouraging. This helped many of them make it big.

For Muslims in Kashmir, it had been a Himalayan battle to choose acting as a career. Part of the problem was the conservatism that acts like a gravitational force. Off late, however, the situation is changing. Actors from Jammu and Kashmir are a crowd now. Some of them are getting very good roles and are being appreciated for their skills. The contact between the artist’s fraternity has reached such a level that now marriages are being solemnised.

Not Many Films

While Bollywood did more than 20 films on Kashmir post-1990 and a lot of Kashmiri actors figured in their cast, there was not a serious effort of filmmaking within Kashmir. While the Kashmir story has already become so touchy and sensitive, there were not many efforts to even tackle the non-controversial aspects of life in Kashmir.

This, however, has been a historic deficit. Jammu and Kashmir has historically lacked a filmmaking culture and there are no funding agencies either. It may be linked to the limitation of the audience. There were, however, a few efforts in the last half a century. Soon after the partition, Ezra Mir directed Pamposh (Lotus) in 1952. Though it fetched her president’s medal and the film was screened at the Cannes Film Festival, it was not liked by people when it was screened in the cinema halls.

In 1964, when Manziraat (the wedding henna ceremony) was screened in Kashmir cinema halls, it was very well appreciated.

In 1972, Jammu and Kashmir’s Information and PR department entered into a joint venture with filmmaker Prabhat Mukherjee for making a film on the life and contributions of Shayar-e-Kashmir Mehjoor. It was a dual-language film and was screened in cinemas and projectors in the villages.

There were some efforts by established TV producers to make films on a diversity of subjects. These included Jyoti Suroo’s Babaji (father), Bashir Budgami’s Rasool Mir and Habba Khatoon and Siraj Qureshi’s Arinmaal. These low-budget products were meant for the TV and that was it.

In the last 15 years, a number of youngsters attempted filmmaking but exposure and budgets were the main limitations. In 2006, however, theatre director and playwright Aarshad Mushtaq made Kashmir’s first digital feature film, Akh Daleel Looluch (A story of love). Set in the early nineteenth century, the film told the tragedy and travails of the 101 years of Kashmir misrule. A few shows were huge successes but the filmmaker could hardly recover part of the costs that had gone into the making of this film.

With cinema reopening and new talent getting into the acting, Kashmir will have to work hard to get into filmmaking. The new generation has started already. They are, however, focused on YouTube. However, it remains to be seen how the cinema re-opening will entice them to go for the big screen.