Bilal Handoo

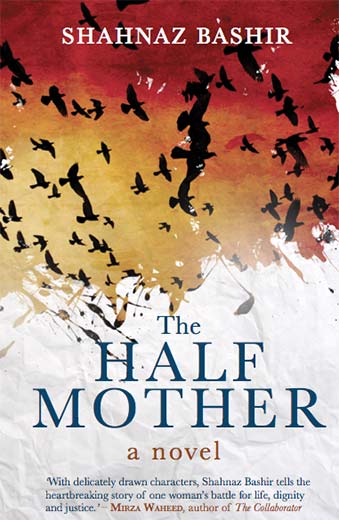

Storytelling, says Zadie Smith (a British novelist), is a magical, ruthless discipline. If Smith’s words are any parameters, then Shahnaz Bashir’s The Half Mother indeed appears a disciplined piece of literature, though, it is poignancy which works magic for the academic’s debut novel. And, much of the credit for it goes to the subject of the novel: enforced disappearances—one of the ugliest realities of Kashmir conflict.

The Half Mother tells a tale of a mother who toils hard till her death to seek the whereabouts of her son. Her search takes her to police stations, army camps, torture centres, courts and NGOs. She faces disappointment everywhere, but exhibits a strange hope to continue her struggle.

Shahnaz mainly focuses on the events which were order of the day during 1990s, and some, even today. The plot of the novel reflects larger dilemma of the relatives of disappeared persons. And through the protagonist (Haleema), the novel attempts to picture the plight of all those mothers who are craving for the company of their disappeared sons.

The author has named his characters very intelligently. The name Haleema implies the motherly affection aptly demonstrated by her struggle and hope. Her son, Imran symbolises budding flower, badly plucked out from Haleema’s garden. Ab Jaan, Haleema’s father symbolises patience and maturity. Shafiqa, Haleema’s neighbour reflects compassion. But the name of Army Major Aman Lal Kushwaha, who enforced Imran into disappearance, contradicts with his actions. He symbolises the larger reality of army in Kashmir—who in spite of being involved in human rights violations in Kashmir, attempts to win hearts and minds of people through its ‘Goodwill Mission’. And the character played by Dr Aiyaash Mir as chief minister of state aptly syncs with the popular unionist leader of the state.

The novel is mostly written in third person which provides narrative freedom to characters. Shahnaz might not have Dickinson’s ability of storytelling, but his prose is nothing short of lyrics. His style of writing is pregnant with pain. And towards the end, the writer uses first person narrative to describe the plight of the journalist while covering the conflict and its offshoots.

At certain places, Shahnaz’s description of events and situations reminds you of Khaled Hosseini’s A Thousand Splendid Suns. But on the whole, Shahnaz has maintained his own voice of narration while weaving the mellifluous prose. And like Hosseini, Shahnaz grips you with his straight crafted sentences.

But perhaps, the essence of The Half Mother is usage of Kashmiri words to describe the heart-wrenching feelings of the protagonist. At certain places, the words like: Kuni kahn chhu na, Gaed ha kaertham patro, Lag’ya balay’i and other Kashmiri sentences readily strike a chord of awe. And given the nature of subject, such sentences only invoke a sense of empathy for the characters.

WG Sebald, a German writer and academic has already blurred the line between academic and writer. One can be best in both. Being an academic, Shahnaz has exercised the writer inside him to the best of his abilities. Only great writers can portray the essence of the story by delving deep into the plight and psyche of the characters. By mapping mother’s pain for her disappeared son, Shahnaz has created a niche for himself in the list of the emerging conflict writers of the world.

The author’s belief that Haleema exists somewhere among the relatives of 8000 disappeared persons in Kashmir has helped him to paint her struggle in a realistic manner. And yes, while spinning the tale, Shahnaz doesn’t leave behind a trail of ambiguity—otherwise, a big problem with academics.

There are already two recent books on Kashmir Conflict: Basharat Peer’s Curfewed Nights and Mirza Waheed’s The Collaborator. Now, The Half Mother. So, as a reader, one expects from Shahnaz’s much-awaited book to offer: departure from the usual. But hang on a second. This is where some of the readers might be turned off—because The Half Mother is the reflection of Kashmiri society rather than a fiction with twisted and turned plot.

And especially towards the end, the novel reflects the reality of relatives of disappeared persons: their endless struggle with the system. While narrating the usual, it seems, the writer hasn’t let his protagonist to take larger than life step—something, which could have provided an alternative to the victims for fighting against the frigid system in a much better way. But, while fictionalising the facts, the writer creates a sense of empathy for the relatives of enforced disappearance among a larger audience outside Himalayan conflict zone.

And yes, Shahnaz will take you back to nineties and will recreate the era for you. His focus on small details makes his work readily acceptable and invigorates bygone memories. For instance, he draws our attention towards the absence of Kashmiri history in our school texts. But overall, his fiction (extension of reality), written at the backdrop of conflict, makes it a good read.