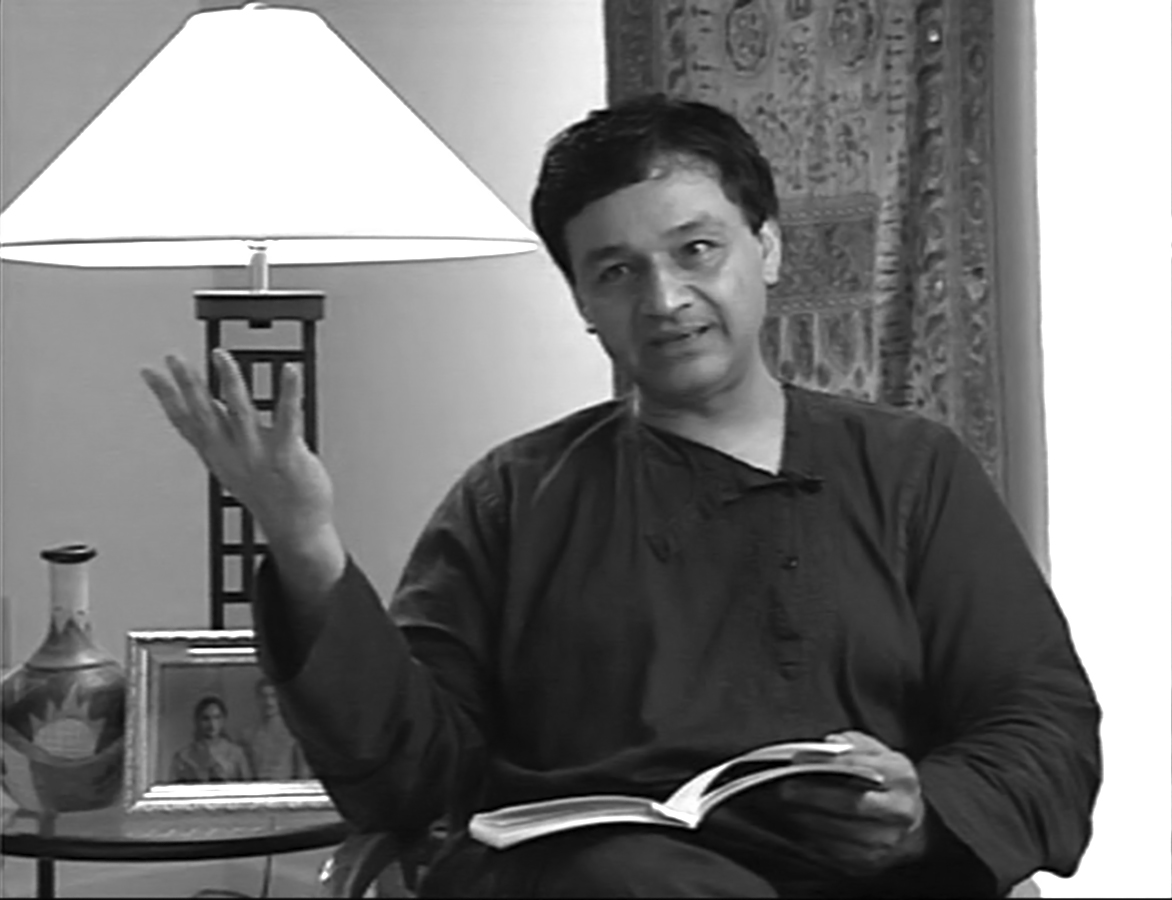

From once lively literary meetings where he rubbed shoulders with the who-is-who of his times to a small dark room in Srinagar, 90-year-old Ghulam Nabi Baba wants to relive his life. Sehar Qazi meets the writer and gets him talking about his life and times

For 90-year-old Ghulam Nabi Baba, author of Sathseder (Seven Seas) and Yate Na Bakaya Haba (Nothing in this world will last forever), being bedridden is like a curse. But what irks him more is his falling memory. His weak lean body has lost its strength, his ears have lost their hearing ability, his eyes have lost their vision, yet he believes immortality of a person or a place lies in its language and literature.

Born at his ancestral house in Nowhatta in Srinagar’s downtown area Baba Sir, as he is fondly known by people, has just one last wish – good health so that he can walk through the lanes of Nowhatta area, the place where he is born and where he spent his childhood.

Most of the events related to Baba’s life are lost to old age. But he still recalls one major event that changed his life to a great extent: divorce from his wife after one year of their marriage. Since then he lived mostly alone in his small house. Presently he lives with his niece and Danish, his adopted son.

He also recalls his childhood days spent at his ancestral house in Nowhatta. “I had four siblings, one of my sisters and the two brothers died long back. I was the only son left. Khaneh Majar Osum (was the pampered one),” Baba says.

Sitting morosely contemplating in a corner of his small house Baba tries to piece together his fragmented memory. Finally, after a long pause, he recalls Ghulam Ali Baba, his father, who was well versed with languages like Farsi (Persian), Urdu, Kashmiri. “My father is my inspiration. He used to narrate us the stories in wintery nights. I also wanted to be a story-teller and I started writing. He would gather all the children in the family and tell us stories,” says Baba. “I and my cousins would often fall asleep while listening to his stories. Nun chai (salt tea) in the Samavor with katlam and bikerkheni were relished by all,” recalls Baba.

In 1949, after completing his honours in Urdu, Baba joined Radio Kashmir. “I had heard that Radio Kashmir was appointing people who were related with art and literature. I was interviewed and appointed there. I was selected by Sanaullah Kalandar as an artist,” Baba remembers.

In between the conversation Baba abruptly asks, “Did you write about my school and about my house at Nowhatta? Have you seen the government school at Nowhatta? My house was exactly in the same place.”

After 11 years, in 1960, Baba left Radio Kashmir. “During that time there was no pension scheme. I joined the Department of Information (J&K). Because of my hard work, I was promoted as a producer within a few months of my service. I was told by Bakaya Sahab, who was the director at that time to go to Kargil and join as an Assistant Information Officer. I refused because of my sister’s health conditions,” Baba says. “Later she died after her prolonged illness,” he adds with a change of voice.

The memories that Baba could recall without much effort are from his days at the Radio Kashmir. “Initially I was a newsreader and later I started writing. I was the part of gaomi program (program that is written about the life and issue in the rural areas). I wrote plays. I often would act in those plays. My name was Jaffar Bhat in one of the plays. My father was…I don’t remember his name. He was a Pandit,” he says with a smile.

“From 1949 onwards, we used to have meeting, literary meetings. In those meetings takreer (speech), nazam (poem), short stories, plays and the parts of drama (plays) were discussed. As dramas were long in their format, so only a small portion was narrated by the writer,” says Baba. “The topics that were discussed in the meetings were called literary topics. Ghulam Nabi Feraq, Late Ghulam Ahamd Abid, Ghulam Ahmad Ghash, Late Nazir Ahmad Mir, Late Abdul Gani Qazi and some more poets, short story writers used to be part of those literary meets. Writers from the city as well as from the other part of Kashmir used to participate. There was an exchange of thoughts and ideas. On Sundays, we used to have these meetings”.

Trying to recall more about the meetings he says, “We used to discuss the language and the literature written in our own language. I started writing since 1949, and from there, onwards my literary period started. I have read Haqani, Mehjoor, Azad, Prem Chand, Momin Khan Momin, Mirza Ghalib and Allama Iqbal and many others. Among all I often read Allama Iqbal,” says Baba in an effortless tone that defies his age. “We had daily programmes in Radio Kashmir. I wrote for programmes like Kath Bath and Zoneh Dab. I was Zeneh Kak in one of the programmes of Zoneh Dab,” he recalls.

Being a writer Baba is concerned about the changes that took place over the years in language and literature of Kashmir. “Our society got developed in such a way, totally a different way far away from its culture. In the past, everybody was the admirer of our native language. But today we read English literature. Their issues are not our issues. We have our own issues to write about in our own language. We have just abandoned our native language,” feels Baba.

Talking about his love for the Kashmiri language, Baba says, “We used to feel our language while writing and singing Kashmiri songs. The feeling has now disappeared from society. We have lost our essence of being Koshur (Kashmiri), just because many people have lost that love for their own language”.

Baba believes that we should write about our issues in our own language, so that it may influence the world.

In the past, writers used to write prose and poems in Kashmiri, Akh jazbat tahat (out of love and respect for our own language), but now I feel most of us have lost our way and the real issues that we need to write about, feels Baba.

While talking about the words and the structure given to the language, “Many people have tried to give Zann (structure) to the language like Amil Kamil, Rahman Rahi, Ghulam Nabi Feraq, Aziz Hajini, Margob Banhali and many others. People from city as well as from the other parts of Kashmir have come forward to contribute to their language,” Baba says.

“We should not forget our own language. Parents should teach their children Keasheer Zaban (Kashmiri language), so that they can contribute to their society and make it better in every possible way,” he says.

Talking about his books, he says, “My first book was sathseder. It is the collection of seven short stories. I wrote about different issues and evils including dowry and corruption of our society. My second book, Yateneya bakaya haba is the collection of eighteen short stories. I thought of writing about life and death and how one day everything has to end, so I wrote it. In one of the short story I wrote what people do if someone dies in our society, they arrange a Wazwaan (traditional feast prepared on marriages mostly) for that also, even if they can’t afford. And how everything has become expensive especially our marriages. I received letters from my pandit friends regarding my books. They have appreciated my efforts”.

Ghulam Nabi Baba has completely forgotten about the three awards that he has received. When asked about them he refused and replied with a smile, “es che serie musafir, chena?”(We are all travellers, aren’t we?).