(Enter into Jawahar Tunnel: KL Image Bilal Bahadur)

It was once an alternate cart road to main all-weather access routes to Kashmir. A new modern four-lane alignment of the Jammu-Srinagar road, today the only functional over land access into the valley, is being laid. This will reduce travel time between the twin capitals to five hours. A Kashmir Life report.

From a cart road during the Dogra rule, not in the least the main access into the Kashmir valley then, the Jammu-Srinagar road is now all set to be a modern highway in four years that can be driven through in less than five hours. That is if all goes according to the script.

The National Highway Authority of India (NHAI) is laying a highway between the state’s two capitals at an estimated cost of Rs 11000 crores to be completed by 2016. It is billed to be an engineering marvel in the Pirpanchal Mountains. The partially new alignment is designed for a speed of 60 to 80 kms an hour. The 240-kms road will have 14 tunnels, 43 major bridges, 24 viaducts and a number of flyovers and underpasses.

“It will bypass all the towns through which the existing highway passes and that would reduce congestion, accidents and make hitherto inaccessible areas accessible,” said Colonel (retd) M K Jain, NHAI’s Jammu Project Director. One hundred underpasses will connect most of the 156 villages in seven districts through which the highway will pass. The partially new alignment will be shorter by 50 kms compared to the existing road. The project is part of the North-South corridor that is being implemented under the massive NHDP.

(Here is the opening of a new tunnel to Banihal)

For Kashmir, the existing 300-kms defense road that it shares with the army is not a mere handicap in mass movement, trade and the services alone. It gives an impression to Kashmir of being a “gated population”. Barring the air traffic, almost everything passes through the 2.5 kms tunnel, India’s longest highway tunnel, that connects the valley with mainland India. Kashmiris, says one of the former chief minister Mufti Sayeed’s top aides, have been globe-trotters for most of their history. “The partition enforced a new political geography that devoured most of his (Kashmiri’s) access routes to outside world and instead offered him two almost-always-flowing nostrils of Jawaharlal Tunnel. It restricted trade and induced a siege mentality.” That is something the new highway may help change.

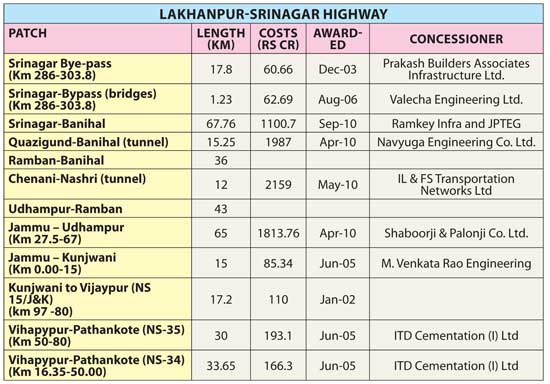

When the then Prime Minister Atal Behari Vajpayee started his ambitious Golden Quad project, the entire 400-kms track between Lakhanpur (Jammu) and Shalteng (Srinagar), was divided in a number of stretches. Initially, a 114-kms stretch from Lakhanpur to Jammu and 17-kms-long Srinagar bypass was taken up and has almost completed at a cost of Rs 952 crores. “These projects are through,” says Jain’s Srinagar counterpart Varinder Singh. “The road between Lakhanpur and Jammu is one of the best stretches, the accident rate has gone down and the travel time has halved.”

As the two extreme ends of the road are ready, the NHAI has finally taken up the main stretch in between. Of the six sub-projects in which the new highway between Jammu and Srinagar stands divided for implementation, four have already been awarded to concessioners (not contractors). In this region, it is the first major project in Private-Public-Partnership (PPP) mode in which the concessioner will design, build, finance, operate and transfer (DBFOT) the project. The NHAI will pay them on annuity basis. Those who bagged the awards include the Ramkay Infra that has tied up with a Chinese company JPTEG to implement one of the valley stretches and ILFS that has outsourced the tunnel job to an Austrian company.

The National Highway IA has an interesting history. It was initially a consequence of the Treaty of Amritsar under which Gulab Singh bought Kashmir for Rs 75 lakhs from the British colonists in 1846. Since Jammu was the seat of power and Kashmir was restive over being sold and purchased as a nation, it needed a direct road link between the two major towns of the heterogeneous state that the treaty cobbled together. Initially, the new political masters would follow the track that Mughals had laid for annexing Kashmir in 1586, or simply crossover to Lahore-Muzaffarabad link to Baramulla and then sail to Srinagar.

Gradually, the requirement for a direct link was felt by the durbar and it was the treacherous alignment of NHIA that Maharaja and his durbar started taking to trek between the two places.

Soon after, this became the Maharajas personal route. Anybody who intended to take this trek had to seek a formal permission that initially the British Resident in Srinagar would issue. It was in 1901 that the first major improvement was ordered by the Dogra durbar. From Jammu to Udhampur, a Cart Road was constructed. Then, Maharaja Ranbir Singh had an idea of creating a rail link so he ruled the route be aligned in grades and curves for a proposed electric railway. Between Udhampur and Srinagar, it was just a dirt track through forests, foothills and along the banks of Chenab. In 1912 one of the Maharaja’s ministers A Mitra, according to historian P N K Bamzai, worked out a plan to construct a road over the Banihal Pass, the formidable 9200 ft high mountain peak of the Pir Panchal range that separates Kashmir from the sprawling Chenab Valley.

Initially, the durbar requested for English engineers from India’s British government. But they could not spare one. So, desi engineers worked on the project. After an investment of around three million rupees, the first horse driven carriage crossed over the pass in 1916. In July 1922 the Maharaja ruled that the road be opened for the commoners. Almost 25 years later, the Maharaja’s successor nephew Hari Singh would lead the fleeing caravan of around 40 vehicles – jeeps and American limousines, carrying the royal family, their treasures and the most important staff members in October 1947 in wake of tribal raids.

As the war between India and Pakistan stopped, this road passing through the unstable zones of young Shivalik and Pirpanchal ranges became Kashmir’s only land route to the rest of the world. Soon after, it was taken over by the state’s Power Works Department (PWD). The state government engaged a German firm Baresel & Kunz that laid the 2.5 Kms Jawahar Tunnel in August 1960. It bypassed the perilous Banihal Pass and reduced the distance significantly. In 1964, the road was taken over by India’s Border Roads Organization (BRO).

(This highway is accident prone)

The BRO later slowly upgraded the road to the double-lane specification and continues to maintain it today at massive costs. The highway was designed for not more than 300 vehicles a day with an excel load of 10 tons. “It is being used by around 5000 vehicles a day,” said Brigadier T P S Rawat, who heads the BRO’s Beacon Project. Most of these vehicles are trucks having an excel load of more than 20 tons.

Unstable formations over which the road passes are a major worry. Snow creats major problems for traffic but even drizzle often forces its closure. This road has particular stretches known for shooting stones, blizzards, avalanches and snowstorms and every one of them takes its own toll, every year. During winters, snowing closes it and in summers frequent rains trigger massive landslides. A 39-kms stretch of the road from Ramban to Banihal falls in seismic zone IV. By an average it is closed for 45 to 55 days in a year.

Geologist G M Bhat who teaches at the University of Jammu says the road has 29 major and 19 minor landslide prone areas. He has identified at least six fault stretches that include the one through which the ‘Murree Thrust’ passes.

Terrified by the caving in of a tunnel in Swiss Alps in early 1999, the then DG ITBP (that guarded the tunnel then) stirred a controversy saying that the twin tube Jawahar Tunnel may collapse anytime. Though the BRO denied it, they did recommend that the old fair-weather road be thrown open for part of the traffic.

Off late, the BRO has managed funds in the ninth five-year plan and improved the tunnel that suffered some damage during the 2005 earthquake.

“When it snows it snows heavily,” says Rawat whose men and machinery survived 12 mudslides and four major avalanches in January. “There was an avalanche that was 16 meters high and 500 meters long and it swept away patch of the road.”

In the year ending January 2012, the BRO lost 32 personnel in accidents and by problems induced by working in adverse climate. “Maintaining the road is a daunting task,” admits Rawat.

At one point of time the road would require around Rs 14 crores for yearly maintenance. “After every five years, we improve the road and now the maintenance costs have gone to less than five crore rupees a year,” says Rawat.

On its part, J&K government has been desperate for an alternative for a long time. In 1997, an Austrian firm ALF Consulting Engineers, along with its Delhi partners was commissioned to carry out a preliminary reconnaissance of the new road realignment.

The expert group using GPS came up with an alignment that would reduce the distance between the state’s twin capitals to around 214 Kms including 50 Kms of tunnels. It was supposed to take seven years with an investment of Rs 1422 crores at 1998 prices.

Later, the same firm was engaged to prepare the Techno-Economic Feasibility Report at a cost of US $ 5,20,000 – which later escalated by many hundred thousand dollars. By October 2000, the state government had paid one installment of Rs 67.37 lakh of a total of 2.67 crores after managing a loan of Rs 1.84 crores from HUDCO at 15.5 percent. Players like Korean giant Daewoo were keen to implement the project but lack of donors ensured the plan went nowhere.

The state government’s failure to own a highway has forced policy makers to be positive and responsive to what NHAI wants. The company will get anything and everything so that the project is ready within the stipulated time. But will NHAI be able to deliver?

The new road under construction will have more than 24 kms of 12 minor and two major tunnels. The two major tunnels are handled as two separate sub-projects. The work on both of them started on July 25, 2011 when the union Minister for Road Transport and Highways Dr CP Joshi flew to the Wuzar village in Qazigund and laid the foundation stone for an 8.45 kms-long tunnel. The tunnel bypassing the main mountain pass of Kashmir between Lower Munda and Banihal will have an additional 690 meters long tunnel attached and both will be ready by 2016. Awarded to Navyuga Engineering Company, this Rs 1987 crores project will reduce the 31 kms distance to a mere 16 kms.

Another tunnel connecting Chenani to Nashri and bypassing the difficult Patnitop and the risky Nashri slips would be 9.35 kms long and would reduce the distance of 41 kms to one-third. It is expected to cost Rs 2159 crores and the concessioner IL&FS Transportation Networks has outsourced its implementation to Leighton India, a subsidiary of a major Austrian company.

The Qazigund tunnel will be double-laned, two tubes which will be interconnected to become escape routes during any disasters. For the Chenaini tunnel, it will be a double lane, single tube tunnel for both way traffic with an escape tunnel of five meters width and 2.5 meters height.

“The Chenani tunnel is the longest and the largest highway tunnel under construction in India right now,” says Singh, who now heads a full-fledged small NHAI office in Srinagar. This tunnel is also slated to be ready by 2016.

In both the tunnels, Singh said, NHAI is using the New Austrian Tunneling Method (NATM). “It means you go building as you go inside and you treat the rocks and create support systems as per the soil system,” Singh said. “It is considered better because treatment and support systems are decided on the basis of the actual strata observation and not on basis of initial exploration.

Around 700 people are working on both the sites and most of them are locals who have hydraulic or railway tunneling background. “We are in the Nashri tunnel up to 600 meters and in Qazigund the progress is 500 meters,” Singh said. “The overall progress on the entire project could be around five percent but we are on track.”

But the project is facing three major problems. Two of the six stretches have not been awarded to any concessioner, so far. The land acquisition process by the state government is expensive and sluggish. Various government departments will take a long time to shift the utilities that follow the road alignment. “This could delay the project,” admits Jain. “But the governments will have to take the decision at the highest level so that we retain the pace we have evolved.”

The two patches – 36 kms between Ramban and Banihal and 43 kms between Udhampur and Ramban – make the middle of the road and are yet to be awarded. At least three efforts failed to get the concessioners for the two projects. Sources in the BRO suggest this being the most treacherous part of the entire length of the road, so there might not be many companies interested in it. But Singh is hopeful. “In the last effort, there were 30 bidders who applied and I hope we will be able to find the best company.”

The project requires 800 hectors (16000 kanals) of land with diverse ownership – forests, state land and the private precious land that grows rice, saffron and apple.

The NHAI executives say this might be the first such road project the company is implementing in which the land component could devour more than eight percent of the total project cost. “We have paid Rs 700 crores to the state government and they have disbursed most of it but Rs 180 crores is still in their coffers,” Jain said. “The costs may go up because every district has crossed the basic estimation of the land costs they had made initially.”

According to NHAI the land that the state government is handing them over has ‘vacant access’ in which various non-state actors prevent any work for one or the other reason.

Land is a highly emotional issue in J&K where the per capita land holding is the lowest in the country. Massive pressures have shot up land costs and it is adding to the unemployment. “It is a tall order and very difficult,” said a senior civil administration officer who is part of the land acquisition mechanism set up in Kashmir. “We have to acquire more than 7429 kanals (371 hectors) of land in 58 villages across four districts and deal with 5059 land owners and it can not happen overnight.”

“We have disbursed Rs 220 crores of the Rs 270.31 crores released to us,” a senior officer in the Kashmir administration said. “We will require additional Rs 304 crores.”

A racket in which a collector in Pulwama swindled Rs 21.57 crores has added to the difficulties with an investigating agency probing the case wanting records for every single penny reinvestigated. “If we follow the instructions of the state vigilance organization (that is probing the case) we may not be able to hand over the land within a year,” an officer said on the condition of anonymity. There are references to the court in not less than 20 cases, which is going to take its own time.

The NHAI has gotten all the required forest clearances. On the basis of the reports of its two consultants – LBG Group and ICT that surveyed the highway in 2007, NHAI had deposited Rs 13 crores for utility shifting costs with the state government. When the NHAI concessioners go to the site, they see the utilities actually increased. Now the NHAI is making a fresh survey.

An additional issue would be when the crucial highway will have many agencies working on its 300 kms length. The BRO that is maintaining it for decades now has made it clear to everybody that it would not maintain the highway with any other agency. In January, when it heavily snowed, the government had to formally request the BRO’s Beacon Project to clear it. “We are people in uniform who work for commitment,” a senior BRO officer said. “They (private players) will be better equipped but will eventually look for the profits.”

Singh said this is part of NHAI responsibility. The concessioners are responsible for laying the respective roads and maintaining the particular stretch of the exiting highway. “We have taken over the 65 kms stretch from Udhampur to Jammu and the concessioner is maintaining it,” Singh said. “The movement will not suffer because of the additional work and expansion.” Snow clearance on the Patnitop was also done by NHAI this time.

“I have not seen anybody taking so much of interest as the Chief Minister himself,” Col Jain asserts. “Even on smaller issues, he (Omar) intervenes personally and helps us to move as fast possible.”

The Chief Minister’s personal interest speaks about the state’s desperation to have an alternative to this run-down road that is literally splattered with blood. It consumes around 200 lives every year and is closed for 45 to 55 days for one or the other reason.