by Indira Guerrero

BAREILLY (UP) (EFE): No one knows where the missing girls in Mahima’s village are, except Mahima herself. The last time she saw one of them, her own, was when she left her womb in the abortion of an unwanted daughter.

No one knows where the others are.

Girls are missing in this village and the neighbouring, and throughout India. No one is looking for them. They do not know about them. Most are dead or unborn.

Over the past 30 years, millions of girls vanished without a trace or died before they reached 6, suspected of being uprooted from the womb before birth, killed, sold, abandoned, or made to disappear by parents. The cost of raising them makes them unworthy of living.

Selective Killing

A United Nations official, in her office in a posh Lodhi Estate neighbourhood of New Delhi, drew a diagram of the sectors of society involved in the disappearances.

“If you look at it, this line goes through the families of those girls, the government, the police, the hospitals, the economy. Everyone is in this, nobody cares, just forget about it,” she said, connecting them to form a loop.

In the late 1980s, reports of newborn deaths from a broken neck within a few hours of birth or due to poisoned milk or suffocation with soaked sheets revealed that the targeted killing of girls was taking place in India. The 1991 census of India set off the alarm bells. The data showed that there were 927 women per 1,000 men against the global average of 952.

Over the years, the brutal killings seemed to have subsided, owing to the monitoring of pregnant women until delivery and the installation of cribs in hospitals for parents to leave their babies in-case they did not want to bring them up. “If your baby is a burden, leave them here,” read the signs at some centres.

Cases of murdered baby girls declined, but the population of women continued to fall. The arrival of ultrasounds in India had started a new system of gender determination and selection. The 1991 census showed that there were 4.2 million fewer girls than boys aged 0 to 6 years.

The situation worsened over the next decade, according to the 2001 census, which raised the difference to six million. In the latest census, carried out in 2011, the difference reached 7.1 million, the Centre for Global Health Research (CGHR) reported in a study published by The Lancet.

In June, the federal Home Ministry published the registration of births between 2016 and 2018, the latest study of sex ratio in the country until the 2021 census is published.

The data calculated from samples from across the country is not encouraging: 897 girls are born for every 1,000 boys.

In July 2019, birth records in 132 villages of Uttarkashi district, about 300 km (186 miles) north of New Delhi, exposed the effectiveness of the practice: Of the 216 babies born in three months, all were males.

She Is My Blood

Mahima consumed mifepristone and misoprostol, two drugs available easily, to terminate her pregnancy.

One is known as “the morning-after pill”, and the other treats stomach ulcers.

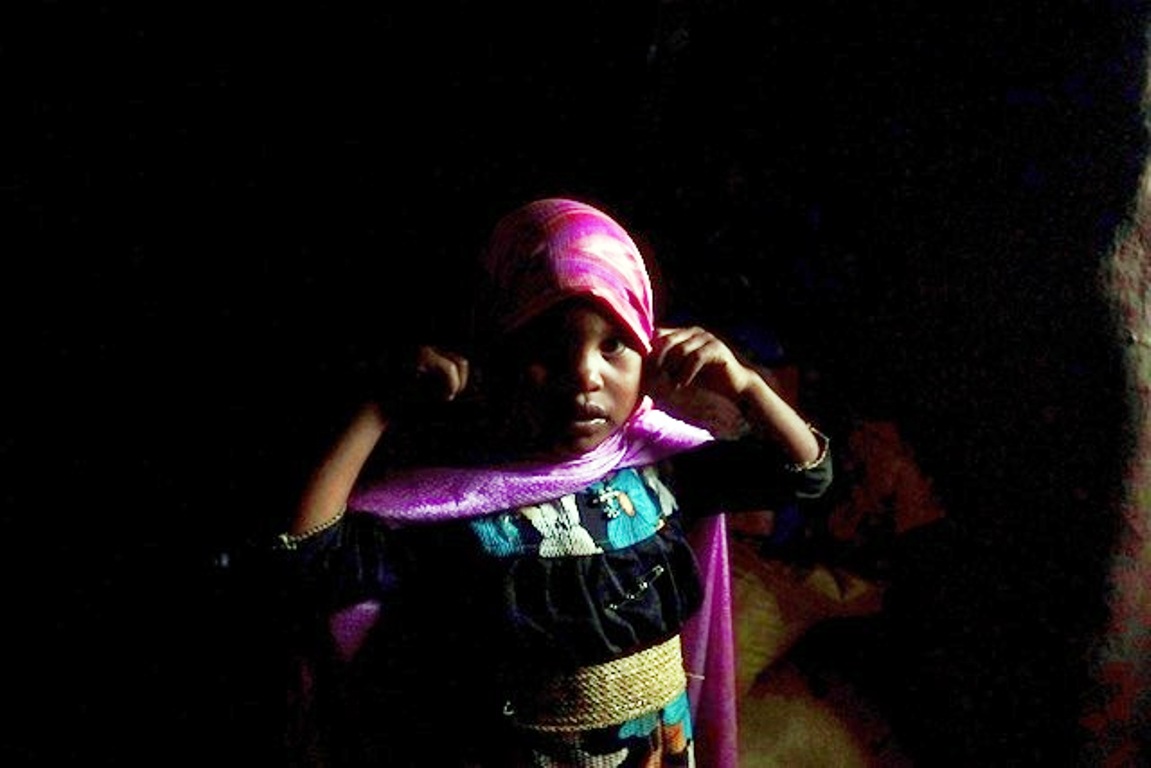

“Because the child was a girl and I wanted a boy,” said the 26-year-old in her mud hut, unrepentant, as she picked lice from her the hair of her son. In a dark corner of the one-room house, her two older daughters, 8 and 10, listened to their mother, little knowing that the reason they are alive is that they were born first.

Mahima believes that the pattern of a reproductive system of a woman determines the sex of foetuses.

In her case, she found that “when a boy is born, then after that only a girl born.”

That is why she aborted her fourth child, convinced that it was a girl.

Indian law allows the use of the ultrasound scan to examine the development of the foetus but prohibits the disclosure of the sex of the foetus to families. A violation attracts penalties ranging from three to five years in prison. The law has given rise to a new practice.

Doctors or ultrasound diagnostic imaging technicians started taking bribes of up to $300 in exchange for making a sign, a gesture or putting a tiny mark on the edge of the receipt to reveal the sex of a foetus to parents.

Mahima had to walk 10 km and then climb into a trailer of a tractor to reach the public hospital in the city.

“He asked me, why are you doing it, you should not do it. But I told him that we did not want a child,” said Mahima, who swears that the doctor did not examine her to check if her baby was a girl.

In exchange for 600 rupees, or about $8, the doctor gave her a prescription to procure the medicines for the abortion.

However, the doctor urged her to continue her pregnancy and give her child to the hospital. But she did not want to do that either and leave the daughter in the hands of strangers. Reports of shelter homes prostituting, selling, or enslaving girls tortured Mahima more than the death of her child. “They told us to give our child to them. I told them I cannot because she is my blood.”

In The Name of Their Fathers

If one is to single out the houses in which at least one girl disappeared, one will also need to mention Amisha, the wife of a peasant with two oxen and half a dozen goats.

The family is well-known in their village for their relative economic comfort.

Amisha is seen outside her home three times a day, when she takes the goats to graze and when she goes out to collect water from a hand pump installed in the middle of the field.

After carrying the last two buckets of water needed to clean the dinner utensils, she earned the right to do whatever she wants, which is often nothing more than untangling the hair of her son.

The long, almost golden-hued mane of her son, Ajay, is a promise she made to the gods if her family was blessed with a son to carry forward the legacy of the family.

Hindus believe that only a male child, or husband in case of the death of a woman, can perform the funeral rites for the salvation of the dead.

Amisha’s responsibility to give birth to a son is more than that of Mahima.

She is married to the only son in a family of farmers. Having at least one male child was the only way to secure her the lineage of her husband and the salvation of their soul.

Amisha had two boys and three girls. But only the first two girls were born.

She aborted the last one using the same mix of mifepristone and misoprostol.

“Yes, I did it,” she replied with a half-smile when asked if she got rid of the baby.

Her husband paid $14 for each month of pregnancy to the doctor, who gave her the drugs to abort. She was three months pregnant.

Amisha said if a wife is unable to provide male children, she goes back to her parents, and the husband can marry again and try for a son. She was referring to an unwritten rule that she calls “the pressure for the marriage.”

In India, a girl goes to the family home of her husband and the two live there to take care of his parents. Having only girls would mean the family line gets extincted.

The Price of Daughters

“Raising a daughter is like watering your neighbour’s garden,” goes an Indian saying that points directly at the dowry system, the money parents pay for the marriage of their daughters.

Ironically, women are seen as the torchbearers of family honour, and dowry is a symbol of social status that allows parents to choose from the best suitors and families their daughters will marry. Dowry is one of the main reasons girls are seen as a burden or a future debt.

“I save some money, half, and the rest we borrow from our relatives. When another woman in the family marries, I have to give money to pay for what they gave me,” said Mahima.

She was talking about a system banned and punishable by the law since 1961 but still in vogue. There is no stipulated amount, it depends on the status of the family. In poor villages, the amount can start at $1,500 in the form of cattle, jewellery, property, or land.

Paying less-than-expected dowry and pressure from the groom’s family for more money sometimes opens another door to death.

The most recent report by the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB), which cites data from 2018, revealed that 7,277 women were killed in dowry-related cases, representing 94 percent of the 7,747 deaths of women recorded in the country that year.

“If a girl is born, we will have to give dowry. If dowry is not given, who will marry the daughters,” said an elderly woman, left alone after the marriage of her only daughter.

Blame The Water Scarcity

“Blame it on the water,” said another elderly woman in the village, who knows that girls are more likely to die if the land is not fertile.

In the absence of rain, families are left at the mercy of hydraulic pumps that barely meet their basic needs while waiting for the annual arrival of the monsoon.

The rest of the year, men leave the village to look for work in the city or as day labourers in areas with irrigation systems.

Villages, like this one, are inhabited only by women who are prohibited from going to work for fear of being abducted or fleeing in search of a better future.

“If we had at least one water well, women could work at home growing vegetables, and parents would have no problem having more daughters,” argued Biju, Mahima’s father-in-law.

Biju’s leg was amputated due to a gangrene infection. He does not work but has five sons who, as custom dictates, will take care of him until his death.

Unlike the situation in this village, fertile land allows for a life prosperous enough to have daughters.

Many districts have experienced that prosperity in the last decade thanks to government-funded irrigation systems.

But what seemed like a solution has further exacerbated the problem. Men from fertile areas began demanding higher dowries to accept marriage proposals coming from arid zones.

The new phenomenon made it increasingly difficult for the women to get married, said Gita Aravamudan, the author of Disappearing Daughters, who, for years, has followed the factors that lead to femicide.

Who Controls The Extermination?

In 1984, social activist and researcher Sabu George realized that girls were missing. He had been studying malnutrition among children in southern India for several years and concluded that they were killing the girls with mass abortions, or immediately after birth, or later by depriving them of food.

Since then, he has dedicated his life to uncovering the extermination.

During the first few years, he monitored the pregnancy of more than a thousand women in Haryana state, an agricultural state north of New Delhi with the country’s worst sex ratio of 861 women per 1,000 men, where he discovered a selection process in every home.

“Most of the discrimination against girls historically in India has been by neglected delivery, that girls get less milk, less good quality food, receive less child care, get less health care.

“What we have seen in the last 20 years particularly is that the most common discrimination has been elimination at the foetus stage,” he said.

We returned with George to Haryana. There he tried to talk to families in one of the districts with the lowest number of women. The people deny that they follow the practice.

George singled out doctors and ultrasound imaging clinics as the cause of the problem, which, in his opinion, is more serious than the fact that a girl is unwanted.

“Girls are biologically stronger than boys, girls survive much better but when you eliminate it in the foetal stage, there is no protection at all because the girl is not even allowed to be born, so there is no resistance,” he said. “They (the doctors) found it was a gold mine for making money, determine the sex and eliminate (the foetus).”

The secretary-general of the Indian Radiological and Imaging Association, Rajeev Singh, is more forthright in saying that the country has a system to blame the wrong person.

The problem, according to him, was that “everyone, including the government, says they are addressing the problem, but in reality, they do not want to and do not want to go to the root of the problem.”

“The question here is: Who are these doctors behind the selection of girls,” he said, adding while it was prohibited to reveal the sex of a child in ultrasounds, the government allowed gynaecologists to do ultrasound examinations. “A gynaecologist is given the power to carry out (an) ultrasound examination, and he also has the legal capacity to perform abortions. Everything becomes very easy,” he rued.

The Indian government refused to comment on the matter to EFE.

A Country Without Women

In societies like India, the disproportionate ratio between women and men poses an uncertain future.

It has long-term consequences and “leads to more systematic violence against and control of women” and, among other things, to more competition in finding a partner, sociologist and researcher Katharina Poggendorf-Kakar said. The author of Women in India cited the trafficking of girls and sold in other regions as an example.

According to the researcher of German origin, based in India, “bought wives, are at times shared with other male family members of the husband,” which adds to the violence against women who are far from home and rely exclusively on their in-laws. Added to this is their exploitation as sex slaves.

“They are called slave brides, the zamindars (landowners) usually marry them to one of their workers. But they are also sexually exploited by the landowner,” Kakar explained.

Thus, according to the sociologist, although many female foetuses are terminated in the womb itself, the risk of being made to “disappear” haunts them until their old age. It is a “systematic negligence” against them, she said.

Bride Trafficking

Hasina was on her way to Haryana when the government published the 2001 census data. Her arrival and that of many other girls were a direct consequence of these numbers. They had all travelled to make up for the lack of women to become wives. They were all from poor states like Bihar, Assam, and Bengal.

Hasina refers to them as “the trafficked sisters.”

In the absence of women, families began paying anyone who could bring any. The need opened up a new market of bride trafficking.

According to the latest report of the National Crime Records Bureau, at least 34,923 women were abducted in 2018 to be forcibly married, more than 95 per day.

Hasina cost her husband 12,000 rupees, about $170.

“I have bought you and I have bought you the way I would have bought a buffalo for 12,000 rupees,” her husband tells her during every fight, to remind her that she was nothing more than a “paro,” a “molki,” which can be loosely translated from the regional Haryanvi dialect as “a bought woman.”

“Paro” was the first word of Haryanvi she learned.

Her husband had not been the first buyer. She arrived in New Delhi at the age of 12 with a “middleman,” who convinced her that he would take her to the national capital for a journey and that her parents had permitted him.

“When I found out, we were already in Delhi,” recalled the 32-year-old woman.

The door is open, and no one stops her, but for her, there is no going back.

“You cannot rescue a paro,” she said. Her father found her 15 years ago, but since she was already married, returning home would bring disgrace to the family.

“Yes, it is fine to buy brides. Otherwise, I do not know where I would have gone,” explained another woman, Basanti, a Bangladeshi. She was bought by her buyers more than 20 years ago to nurse an old-man in Haryana.

She was kidnapped by a family friend who used to visit them to watch television. He sold her for 6,000 rupees, about $84. It saved her life, she said.

At the time, she had been widowed and was five months pregnant, a state that could have condemned her to a life of misery.

The Survivor

In a crematorium of Bareilly, in the northern state of Uttar Pradesh, some people heard the sound of a crying baby coming from nowhere around 6 pm on October 12 last year.

By that time, the workers had gone, and Babu Ram, the watchman, asked a labourer, Aakash Kumar, to dig a grave so that a couple could bury their stillborn baby.

“I was digging with a spade. The spade hit the pot and we heard a baby crying,” said Kumar, 17. He got scared, thinking that some restless spirits of the people buried in the crematorium were crying.

The couple looked at the corpse of their daughter in their arms. But no, the sound of cry was coming from a pitcher kept in a shopping bag and buried inside.

“When he pulled the spade back, the bag came along with it. He threw it. The baby inside again cried, so he ran away,” the watchman recalled. “It was a girl,” said the watchman, who opened the vessel and found a baby weighing barely 1.2 kg (2.65 pounds).

Crimes against children happen somewhat frequently, admits a police chief who does not want to reveal his name. “Just a week ago, we found a dead baby inside of a toilet,” he said.

The police have paid several visits to the area where the watchman and the couple found the baby girl. The place is easy to recognize because the pieces of the vessel are still there. “As long as we do not know who the mother is, it will be difficult to know why someone did something like this,” one of the officials said.

“I think she was buried alive because she is a girl,” said Akash.

After two weeks in the hospital, nurses have begun calling the girl “Baby Sita” after the selfless wife of Hindu god Rama, one of the most prominent female figures in Hinduism.

One, two, three, four, five, repeats Ravi Khanna, a doctor, four times to count while smearing and rubbing sanitizer on his hands before lifting the plastic that covered her incubator.

“She is a fighter because as per my estimate she was in the pitcher for at least 2.5 to 3 days before she was discovered,” the doctor said. The baby girl was able to survive at a depth of nearly one meter because oxygen was in the vessel, and she remained in a state of semi-hibernation like a bear. She survived without water is a miracle.

The doctor ruled out sex selection as the reason behind the incident and said that there are “children of both sexes” as he reviewed nearly 20 incubators there. “Wait. Well, right now, yes, Sita is the only girl,” he added.

(Written with inputs from Ujwala P and Atul Vohra. Original in Spanish edited by Moncho Torres and Javier Marín. Translated by Parul Dua and edited by Sarwar Kashani. This news feature is being exclusively published in a special arrangement with the EFE, the Spanish global news agency.)