After overcoming the parental hurdles, a young man driven by community sense started working to put Leh on tourism map. Fifteen years after, both tourism and the man is thriving in the cold desert. Bilal Handoo reports the rise of man alongside Ladakhi tourism

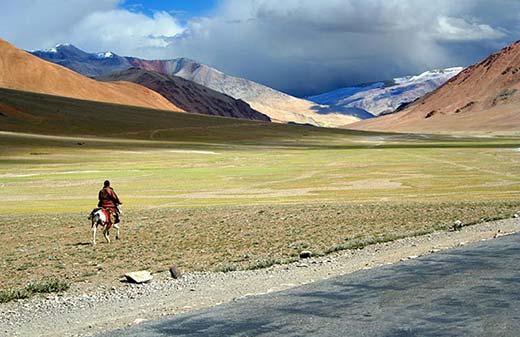

Pic: Bilal Handoo

Two neighbouring nuclear powers were locking horns in the hills of Kargil in 1999. A spillover of each bang would reach miles away from the warzone. Some 215 kms away, Leh was looking deserted. Hardly any tourist was turning up. Most people were cursing war for their sufferings. But not everyone was on cursing mode. A young man, fresh from his Masters in Tourism, sensed a chance in the looming crisis. He changed the worldview toward the cold desert with his single chair and table office. And soon, there was a tourism boom in Leh. Fifteen years after, the man has risen to become a multi-millionaire travel agent of Leh.

At 40, Tundup Dorjey looks happy man as he walks inside his well-furnished office in the main market of Leh. Outside his office window, it is a busy street crowded with shops and shoppers. A few Kashmiri handicraft traders sitting on shops are keenly attending tourists; others are busy wooing the wandering foreigners around. Eateries, travel agencies and shops selling Ladakhi cultural items make it a crowd-pulling place in Leh.

At peace with the buzzing rush outside, Dorjey is presently one of the biggest tourism players of Leh. It was he, who triggered a tourism rush in Leh in 1999 when streets were deserted and smeared with blood in neighbouring Kargil. He did exactly what Wall Street often preaches in the times of crisis: Invest when there’s blood in the streets.

But behind his investment, he had a larger interest in mind. “I wanted to flip the tourism scene of Leh,” says Dorjey, wearing a smiling face.

Perhaps the same motive has made him a household name in Leh at present. He doesn’t operate with his single chair and table office anymore. Time has changed, so has his lifestyle. Today, he is a proud employer of 35 people (only graduates or post-graduates) in his Overland Escape Touring Company.

As he recalls his 15 years stint as travel agent, he falls short of words. “Primarily,” he softly speaks, “two reasons motivated me to be a travel agent: one, travelling; second, interaction.” He takes another pause. “And the only way to sustain the dual passion was to do something related to tourism. And that is how I landed in travel agency business.”

For somebody like Dorjey hailing from Leh’s Chushot village, going this far in life was unthinkable at one point of time. Like many in Leh, he was born in a poor family. Growing up in such a family was not easy. Life, as he describes it, was simply tricky.

But the young Dorjey fought hard to improve his fortunes. He did a part-time job; besides worked as a part-time tourist guide to take care of his needs and that of his family. “I won’t say that I was leading a different life,” he says. “But yes, I always had a strong will to change my life and that of others.”

By mid-nineties, much to his parent’s chagrin, Dorjey left home to pursue tourism studies in Chandigarh. “At Leh Airport, I pledged that I will return to serve my society with the best of my abilities,” he says.

The moment he returned, the war clouds were hovering over Kargil. The panic had reached Leh. It took a heavy toll on tourism. Unlike others, Dorjey sensed an opportunity besides a responsibility in that situation.

To begin with, he wrote a travel guidebook Reach Ladakh. And to spread a positive word about Leh, he also started a webpage. With guidebook and web portal, he started making inroads in Leh tourism, which was then quite medieval.

“But my parents didn’t like the line I opted,” he says. “In fact, my father, a paramilitary man, strongly opposed the move.”

Dorjey, however, followed his heart. But then publishing a guidebook was still a concern for him. He had no money. There was no question to ask help from his already displeased parents. But to his good luck, his wife came to his rescue. Married since college days, Dorjey sold his wife’s gold chain to raise money for book publishing.

Immediately, he sent 200 copies of his published guidebook to travel agents across India and foreign countries to make good contacts. “In those days, tourist agents of Ladakh had to work with their counterparts in Delhi to organize tours in Ladakh,” he says. “Other than that, there wasn’t any source for a tourist to get information about Ladakh.”

‘Cashing on crisis’ is an old business dogma. Perhaps Dorjey was quite mindful of that. That’s why he published his guide book at a time of crisis. “But since it was a war time,” he says, “I mainly focused on spreading positive word about ground situation. And, it indeed helped.”

Located at an elevation of 3,000 meters, Ladakh region is bifurcated in Kargil and Leh districts. The region is known for its remote mountain beauty and culture. In Leh, where Buddhism is the religion of the majority, the most attractive features are the Buddhists Gompas (Monasteries). Apart from providing information about these places, his guidebook also informs about new destinations like Turtuk, Lastang, Sanjak and many more.

One year after publishing his guidebook, Dorjey, then 26, started a small travel agency in 2000. Two things immediately benefited him: one, his Masters degree in tourism (from Pondicherry Central University in 1997); and second, his experience working as part time tourist guide.

He operated from a single chair and table office. But going wasn’t that great at outset. In his first year, only two clients turned up. But unlike others, he didn’t give up in the face of his sluggish sales.

It was the result of his resilience that saw his turnover touching Rs 60,000 in 2001. This made his family very happy. It never stopped there after. Then it became Rs 6 lakh, and soon after touched Rs 60 lakh and eventually rose to Rs 6 crores over the years.

He shortly travelled to India, Tibet, Europe, Malaysia, Cambodia, Bhutan and Nepal to market his venture. It is because of that tireless effort that today his yearly turnover has touched around Rs 16 to 17 crores. “Two immediate things worked in my favour: one, I pay everybody on time; second, I serve my clients well,” he says.

Besides his business ‘ethics’, he says, travel agents in Leh weren’t willing to woo domestic tourists when he started. “But I worked with both foreign as well as domestic tourists,” Dorjey says. “This too helped me in swelling my tourist baseline.” He handles around 10,000 tourists in a season; 70 per cent of them are Indian and rest foreigners.

Ladakh as a high altitude desert is famous for mountaineering, trekking, cycling, motor bike tour, wild life tour, events and conferences, cultural tourism, Jeep safari and river rafting. Dorjey’s touring company provides all these adventurous trips. “I am also expanding my tourism operations in Tibet, Nepal and in many parts of India,” he says.

Since January 2012, he is also running a fortnightly Reach Ladakh that has readership of around 1050. “At Reach Ladakh, we don’t target a particular person or an institution,” says Rinchen Angmo, editor Reach Ladakh. “Our motive is to give information about local happenings like increasing use of alcohol, increasing rate of road accident, environmental issues and so many others.”

Before Reach Ladakh established itself as main publication of Leh, magazines like Melong and Magpie were mostly read in Leh before they stopped publishing. “From business point of view, running a journal isn’t profitable. That’s why those magazines stopped publishing,” he says. “But then Reach Ladakh isn’t about profit. It is simply a mirror of Ladakhi society.”

Apart from being a successful travel agent, Dorjey is having a big say over tourism community of Leh. It was he who hired Nepali cooks in his company with a local helper. “There weren’t many local cooks available earlier in Leh,” he says. “Now we have 90 per cent local cook and 10 per cent Nepali cooks. I am pleased that a much needed change has swept over.”

Besides when non-locals drove men and machinery from outside some years ago to dictate over the tourism scene of Leh, many locals took a firm stand against littering created by these non-locals. “Locals in Leh protested and boycotted them,” he says. “Later, an agreement was signed where it was decided that no non-local can own or run a hotel, travel agency and vehicles in Leh.” The motive, he says, was to benefit the locals without allowing any non-local to call the shots.

But he regrets that tourism boom in Leh created negatives like drugs, cross-cultural marriages and disintegration of Ladakhi culture. “The only way to control it is to regulate tourist influx in Leh,” he believes. “If it goes unchecked, then in the long run, it will disintegrate the Ladakhi society completely.”

Since 1999, he has been working daily 15 to 16 hours without taking a break. He has returned that gold chain to his wife a long time back with lots of other gifts. His parents aren’t displeased with him any longer. His success, he believes, has come by helping others to grow. “I don’t want to be jack of all trades,” he says. “And that’s why, I want to employ more and more people.”

Meanwhile, he seems still at peace with the tourist buzz outside his office. Before taking a long pause, he says, “I am a travel agent and will always remain a travel agent.”

Fifteen years on, bang in the cold desert has indeed turned into a boom.