-closed down. He is now trying to set up a small business along with his childhood friend. But he is unsure of its success. Mirza often wonders about the meaning of this ‘freedom’ after years of imprisonment for a crime he didn’t commit.

Three of his sisters were married off while Mirza was in Tihar jail. One of his brothers struggled to make a living for his family by running a coaching academy, and working overtime.

I can get back the things I lost, Mirza says, but what about those years that were taken away in jail? Who will bring back those years? Then he looks away, and asks after a melancholic pause, “What is the purpose of life after 14 years of your life are taken away?”

There are many like Majid and Mirza who had to suffer years of indignity in jails before being declared innocent. Their implicators, often personnel of the special cell of Delhi Police, always went unpunished despite the courts saying at different times that the arrests were wrongful and evidence deliberately fabricated.

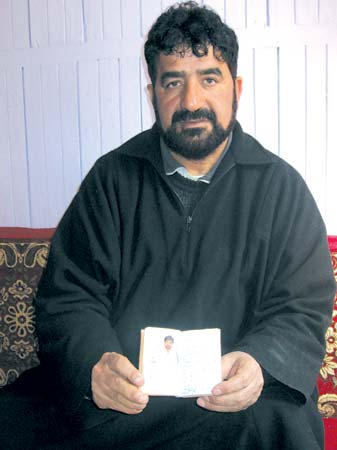

Shakeel Ahmad Khan, then 39, had a government job in state motor garages when the situation worsened in the valley in 1992. Like many of his friends, he left for Delhi from his Hazratbal residence to find some work, and arrived at his friends place in Lajpat Nagar. On April 24 that year, soon after his arrival in Delhi, the operations cell of Delhi Police, who charged him for carrying explosives and a conspiracy to kill BJP leader Murli Manohar Joshi, arrested him.

Along with seven other Kashmiris arrested that day, Shakeel was taken to operation cell of Delhi Police at Lodhi road where he was interrogated. “We were arrested on April 24 but they showed our arrest on 29 April,” says Shakeel. “They told the media that we are some big terrorists who had come to kill BJP leader Murli Manohar Joshi,” he says. Shakeel was charged under draconian Sections 4, 5 of TADA, Explosive Substance Act and 120 B IPC 25/54/59 Arms Act.

He was kept for a month in the ‘operations cell’ of Delhi Police in Badarpur and Lodhi colony. “We were severely tortured in the operation cell. They wanted a confession from us, but we were innocent and didn’t say anything,” says Shakeel.

After a month of detention in the operation cell, along with seven other Kashmiris, Shakeel was sent to Tihar jail by a Delhi court. In 1996, after four years of imprisonment he was released on bail. But he had to regularly appear in the Delhi court for his case hearing. And every time he had to seek permission from the court to return home to Kashmir. “The court also kept a condition for us that in Srinagar we should make ourselves available at the concerned police station.”

Shakeel says the years following his release in 1996 were the toughest and financially draining for him. “I had to suffer more as after every 15 days I had to travel and ensure my presence in the Patiala House Court,” he says. Since he was the only earning hand at home, his family suffered because of his frequent summons to Delhi. “I also had to arrange money for travel and staying in Delhi after every fifteen days for the hearing of my case,” he says. Shakeel regrets that his elder son, who was studying in middle school at the time of his arrest in 1992, had to leave school to support his family.

Shakeel says the years following his release in 1996 were the toughest and financially draining for him. “I had to suffer more as after every 15 days I had to travel and ensure my presence in the Patiala House Court,” he says. Since he was the only earning hand at home, his family suffered because of his frequent summons to Delhi. “I also had to arrange money for travel and staying in Delhi after every fifteen days for the hearing of my case,” he says. Shakeel regrets that his elder son, who was studying in middle school at the time of his arrest in 1992, had to leave school to support his family.

A decade later, on August 2, 2002Shakeel was finally acquitted of all charges by a Delhi court. Everything about his life back home had changed for him and his family.

Shakeel says the years after coming out on bail were the toughest for him. After every couple of weeks, he had to make travel arrangements to leave for Delhi. “Some days I would reach Delhi and leave the city on the same day of my case hearing,” he says. “I was afraid of staying in Delhi even for a single night as police would come to hotels to enquire about my stay.”

The memories of his long trial haunt Shakeel to this day. In 1999, at the time of Kargil war, Shakeel remembers a day when he was sent to Tihar jail by the court for another 15 days of imprisonment. It was a punishment they gave me for being late by just an hour for the court hearing, says Shakeel.

Shakeel, who is in his fifties now, remembers those five sleepless days and nights as the court was expected to give a final judgment in August, 2002. After five days of arguments and counterarguments, Shakeel remembers a faint smile the judge, S S Dingra, gave to his lawyer.