by Saima Bhat

SRINAGAR: After retiring to bed around midnight, when a young man in his thirties felt a wave of pain in his chest, he alarmed his family. Moments later, he was driven to the nearby health centre and eventually referred to SMHS in Srinagar. He had died before being seen by the doctors at SMHS.

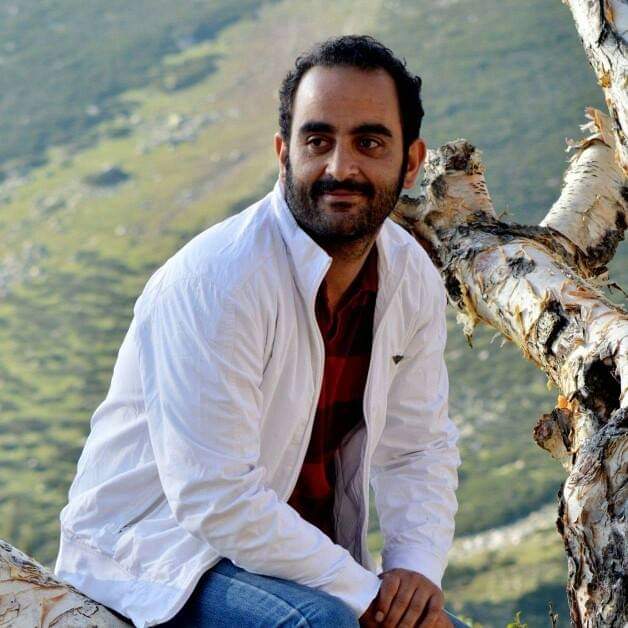

By around Friday dawn on November 20, everybody in Kashmir knew that one of Kashmir’s youngest and finest journalists, Mudasir Ali is no more. His death was attributed to his cardiac arrest. This was the second such case in less than two months.

A resident of Chrar-e-Sharief in central Kashmir’s district Budgam, Ali had no apparent ailment. He was working with Greater Kashmir for the last more than a decade now and also contributed to other publications regularly.

But his friend, who is a doctor, says Mudasir may have actually died of ‘pulmonary embolism’. “He had met an accident and his leg had got fractured. After removing the cast, he still had swelling in the leg. I think his symptoms, which he had informed his family about like breathlessness and pain in the chest could have been because of that. He was taken to the health centre from where he was referred to SMHS but if the doctor had given him heparin and put on oxygen he could have been saved. From Chrar to Srinagar, it takes almost 50 minutes,” said his doctor friend.

But Mudasir’s case is not in isolation. Another journalist Javid Ahmad, 31, a resident of Watergam village in Rafiabad Baramulla, was working as a defence correspondent of Rising Kashmir. He had a cardiac arrest when he was on his way to Srinagar on October 01. Travelling in a local taxi he collapsed when the bus reached Pattan.

Both these reporters were below 40 and none of them had an underlying medical problem that could be linked to their heart attacks. Reportedly they were neither smokers nor had any issue of job insecurity. Earlier also, Maqbool Sahil met the same fate while he was riding his bike.

“The hearts of our youthful friends and colleagues are stopping suddenly,” journalist Muzamil Jaleel wrote on his social media handle. “There is so much grief in our lives. There is so much unbearable pain that we see and feel every day. Living, working, existing is a never-ending struggle. And the good among us, those who aren’t numb already, can’t take it anymore. When will we start living again, when will our land stop seeing the frail shoulders of parents carrying the coffins of their young children…when will we resume dying of old age…when will we start telling the happy stories.”

Journalists across the world live highly stressful lives. These are all the more complicated in situations like Kashmir.

Journalists have their own typical routine where they are always running to meet deadlines. “Our lives are different. We have a different lifestyle, where we usually follow a routine that our jobs dictate rather than what ideal life is all about,” said a senior journalist in the field for more than three decades now. “This lifestyle gets all the more complicated in situations like Kashmir. A general impression is that the level of anxiety and tension is abnormally high among Kashmir reporters and editors.”

Understanding the need to address the issue, three years ago in 2017, Doctor’s Association in Kashmir (DAK), organised a free medical camp. The aim was to screen the journalists in Kashmir for various ailments. As many as 70 journalists were examined by various experts and various tests were carried out. Most of these journalists were below the age of 40 years.

As per the findings of the camp, most of the journalists were diagnosed with stress-related problems, including hypertension, increased sugar level, which most of them were not knowing, deranged lipid profile and fatty liver.

Reacting to the findings, Dr Mir Mushtaq, a senior member of DAK suggested journalists that they should re-organize their priorities and take some time out for themselves and spend time with their families and friends as they are working under challenging situations.

Journalists working with local media, with whom Kashmir Life spoke to said that they are working under immense stress. While there is job insecurity on one side, they said they have inadequate incomes.

“In these times, a journalist after completing his post-graduation gets less than Rs 10000 a month and continues to have a deadline dilemma and pressure from the management to perform. How you expect a person to remain at peace,” said a young journalist who has just joined the field.

Lamenting over the nature of the job, a female journalist told Kashmir Life that there is no distinction between a qualified and unqualified in this profession. “See anybody with mike and camera is a journalist,” she said. “There is no difference which at times puts us in an awkward situation.”

With the existing difficult situation, the condition post-August 5, 2019, changed drastically. The stress has grown immensely, both on the financial front and fear of being reprimanded by various law enforcing agencies.

Kashmir media, the stakeholders say “walks the razor’s edge for the past three decades, facing pressures from all sides of the conflict.”

In the last thirty years, Kashmir media lost more than 13 journalists and suffered direct attacks, intimidation, threats and pressures from various quarters.

“After August 5, other than to perform we have to have self-censorship so that the government agencies don’t create any hurdles in our work. We don’t have a free environment to work,” said another senior journalist.

Outside the journalistic community, the psychiatrists dealing with the crisis also believe that in Kashmir the journalists are having a difficult time.

“Kashmiri journalists are mostly stressed and I am saying this out of my experience because I have many friends who are journalists,” says Dr Arshad Hussain, the leading psychiatrist in Kashmir. “I have seen more stress in journalism than any other profession. This job is very tiring and then there is no job security. And for the last two years, these issues have increased.”

Dr Hussain says a journalist can only be a journalist. “They are caught in. They don’t get sync with other works.”

“Some of these journalists have families, some are planning to get married and some have their families dependent on them and then they have a limited salary and they are not able to pay the medical bills, or take care of their families, which add to their stress levels. They always work under double-edged swords, of performing every day and then the pressure to run their families,” says Dr Hussain.