by M Saleem Beg

INTACH Kashmir has been involved in mapping, documenting and preserving the Cultural Heritage of Kashmir for the past two decades now. Some of the major programmes that we initially engaged with related to the built heritage of the region, include the Conservation of Aali Masjid, Amar Singh College, Mughal Gardens as well as reconstruction of the Dastgir Sahab Shrine, Khanqah-i-Maulla and other projects of similar nature.

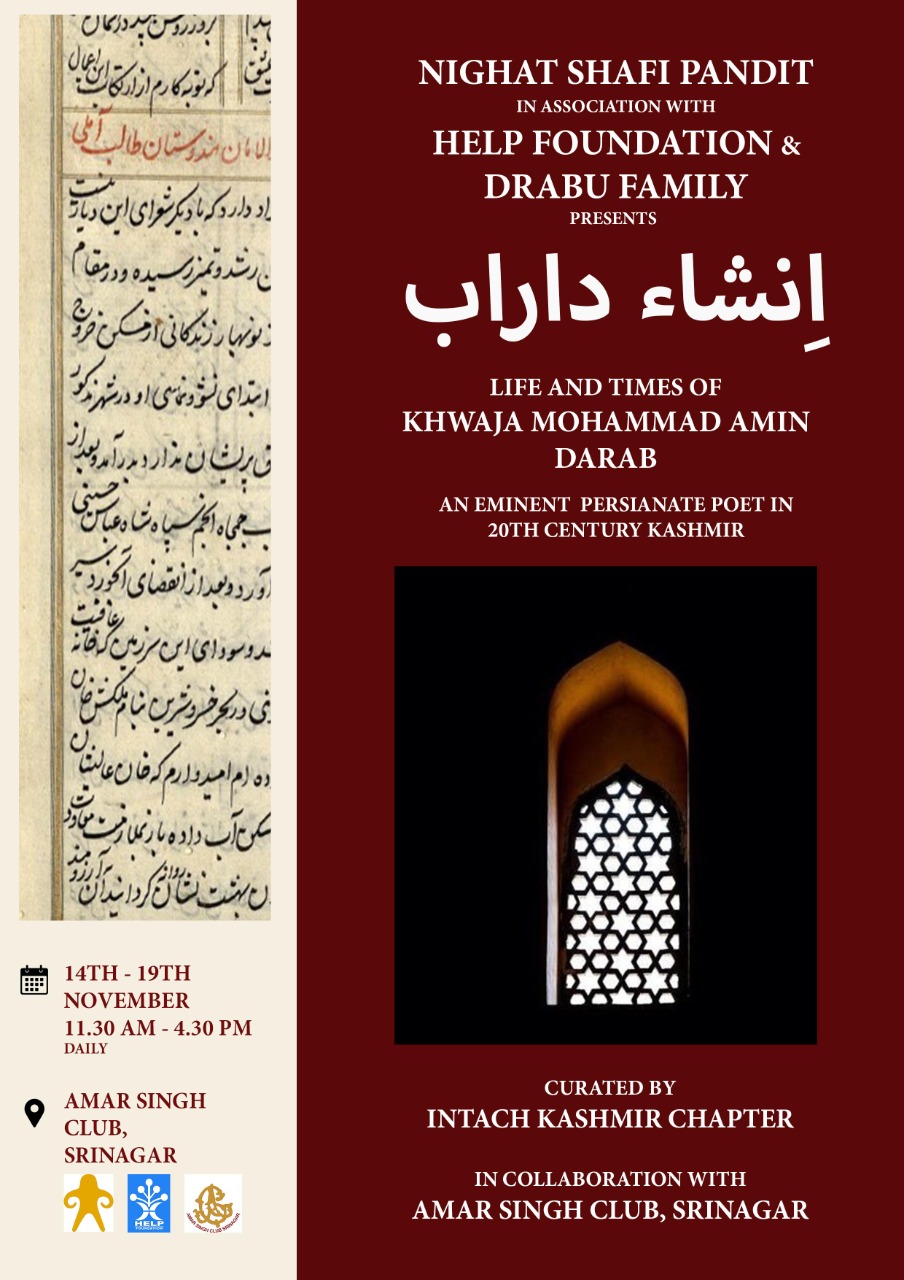

Despite its limited resources, INTACH has actively engaged in efforts to preserve and promote both tangible as well as intangible heritage of this culturally rich land. Besides, promoting a better understanding of the past, numerous exhibitions were curated on Calligraphy, Urban Spaces, Sacred Architecture and Manuscripts in Srinagar, Jammu and Delhi.

We have been on lookout for the archival, oral and textual material, which to our understanding though scattered and undocumented, is available in individual or institutional possession. This material is an important resource that helps in unravelling the rich cultural legacy of Kashmir. The present exhibition is a significant effort in this direction.

The Genesis of Insha-i- Darab

A call from Nighat Shafi Pandit in early 2022, inviting me to see a cache of manuscripts she had come into possession proved intriguing. The manuscripts forgotten and locked in an old rusty suitcase had been acquired by her from the family of Khwaja Mohamad Amin Darab many years back. Though the trunk had already been examined before, yet somehow it had failed to excite the interests of the examiners. Yet, she persevered, safe in the knowledge that the trunk at the very least enshrined a cherished memory.

1. Sometimes curating an exhibition can be rewarding in a manner you would never have thought about. While working on the exhibition of a significant 20th century Persian poet of Kashmir, Khwaja Muhmmad Darab, came across this qitah-i tarikh to commemorate Reza Shah Pehalvi’s pic.twitter.com/DCcJ04shxU

— Hakim Sameer Hamdani (@HamdaniSameer) November 15, 2022

So we opened the trunk in presence of her husband, Mohammad Shafi Pandit, and Pirzada Muhammad Ashraf and it revealed the archives of the last major Persianate poet of twentieth-century Kashmir, Khwaja Muhammad Amin Drabu. We at INTACH found this personal archive to be of rich cultural value and memory that unfolded the life and times of Darab Saheb, his scholarly pursuits, interest in educational and craft merchandise. We mined into the collection and examined folio after folio and assembled a selection into a thread that gives an insight into his life and also the times and the then prevailing cultural and literary landscape. Also, it brought to the fore his way of engaging with the community, scripting for them invites, writing marsiya on the passing away of eminent persons and versified tarikhs on deaths qita-i tarikhs or for inscribing the verse on inauguration of a shrine or mosque, religious and educational activities.

That is how the idea of an exhibition took shape within INTACH.

Persian in Kashmir: A Brief Overview by Professor Mufti Mudasir Faroooqi

Among several centres of Persian learning that emerged in the Indian subcontinent following the establishment of Muslim rule, Kashmir enjoyed a distinct position. Kashmir’s cultural ties with Persia, as some archaeological findings suggest, date back to ancient times. But it is with the beginning of the Muslim rule in the fourteenth century that Kashmir became a great centre of Persian scholarship, creating a fertile ground for the growth of native writers and attracting distinguished men from Iran and the rest of India.

Because of its strong cultural, religious, literary and even climatic affinities, Kashmir came to be known as Iran-e-Sagheer (little Iran). During Sultan Zain-ul-Abidin’s rule (1420–70) Persian received an unprecedented impetus. Himself a poet and a great patron of learning, he is credited with establishing a Daar-u-tarjama, or a translation bureau, where scholars translated texts from Sanskrit and other languages into Persian and from Arabic and Persian into Sanskrit and Kashmiri.

Persian also gained immense importance with the arrival of Sufis and preachers from Persia and Central Asia, who poured into the Valley to disseminate the Islamic faith. The most important of these was Mir Sayyid Ali Hamdani, the famous Sufi saint and missionary who, in the words of Allama Iqbal, laid the foundations of this ‘little Iran’. From the fourteenth to the late nineteenth century, Persian was not only the language of administration but the primary language for all kinds of writing: historical, literary, religious and political. Kashmir can rightfully boast of its poets, theologians and historians who produced great masterpieces in Persian. From Muhammad Amin Uwaisi (d. 1484) known to the Kashmiris as Woosi Saeb to Muhammad Amin Darab (1891-1979), Kashmir’s Persian poets have made a rich contribution to literature and many have been acclaimed for their craftsmanship in Iran too. Only a few can be named here.

The foremost poet of the sixteenth century was Sheikh Yaqub Sarfi (1529-1594) a versatile genius, extremely well-schooled in several sciences such as theology, jurisprudence, grammar, mysticism, rhetoric, Quranic hermeneutics and poetry. Sarfi was a prolific writer and, as poet, he is known for his excellent quintet of masnavis, a khamsa, written in imitation of the famous classical Persian poet Nizami.

It was with the beginning of the Mughal rule in Kashmir in 1589 that Persian reached its zenith. Many Iranian poets travelled to different Mughal courts and some, finding the Indian climate appallingly inclement, visited and settled in Kashmir. Kashmir’s beauty had already become a favourite topic with many of them. To the Indian climate, which many of them described as jigar khwaar, or heart-consuming, they found an ideal alternative in Kashmir. Some of the eminent Iranian poets who visited Kashmir in the seventeenth century include Sa’ib Tabrizi, Abu Talib Kaleem Kashani, Muhammad Quli Salim Tehrani, Muhammad Jan Qudsi Mashhadi and Mir Ilahi. All except Sa’ib died in Kashmir and were buried in mazaar-u-shu’araa, a graveyard reserved for the poets. If Sa’ib, Kaleem, Saleem, Mir Ilahi, Qudsi and Tughra Mashhadi were the Iranian representative voices, Kashmir offered its native talent through Fitrati, Mulla Zehni, Mehdi, Fani, Ghani, Juya, Guya, Saalim, Auji and others too numerous to name.

Kashmir’s greatest Persian poet, however, was Mulla Tahir Ghani, better known as Ghani Kashmiri (d.1669). Greatly admired by many eminent poets and critics including Mir Taqi Mir and Iqbal, Ghani’s forte lies in his remarkable use of language to create poems with multiple layers of meaning. This, along with his versatility in creating delightful metaphors and images, makes him one of the few medieval poets with a striking appeal to the modern reader.

Persian also greatly influenced the growth of Kashmiri literature. Poets writing in Kashmiri found literary inspiration in the works of the Persian poets of the classical age. From the eighteenth century onwards we find poets of the Kashmiri language such as Mahmud Gami, Momin Saeb, Maqbool Shah Kralwari and many others consciously adapting the works of Persian poets like Nizami Ganjavi, Fariduddin Attar, Jalaluddin Rumi and Jami, thus pioneering a new genre of translation-adaptation in the Kashmiri language. While those writing in Kashmiri modelled their works on the past masters of Persian, many continued to write in Persian. One of them, Hameedullah Shahabadi (d. 1848) was an excellent poet and prose-writer who, among other things, wrote about the oppression borne by the people of Kashmir under different regimes.

Persian enjoyed patronage and prestige in Kashmir till the late early twentieth century and for about 600 years it was the language of our faith, administration and knowledge. In 1889 CE it was replaced by Urdu during the reign of Maharaja Pratap Singh. This socio-cultural shift notwithstanding, Persian has not lost its charm for the Kashmiris even today. Iqbal, in a Persian verse, exclaims:

tanam guli zi khayabaan-i jannat-i Kashmir

dil az hareem-i hijaaz u nawaa zi sheeraz ast

(My body is a rose from the rose bed of Kashmir

My heart is from the sanctuary of Hijaz, my poetry from Shiraz).

The fact that Iqbal’s verse still resonates with the Kashmiris is a testimony that Persian has had a formative influence in shaping their self-perception as a people and will continue to attract them in future as well.

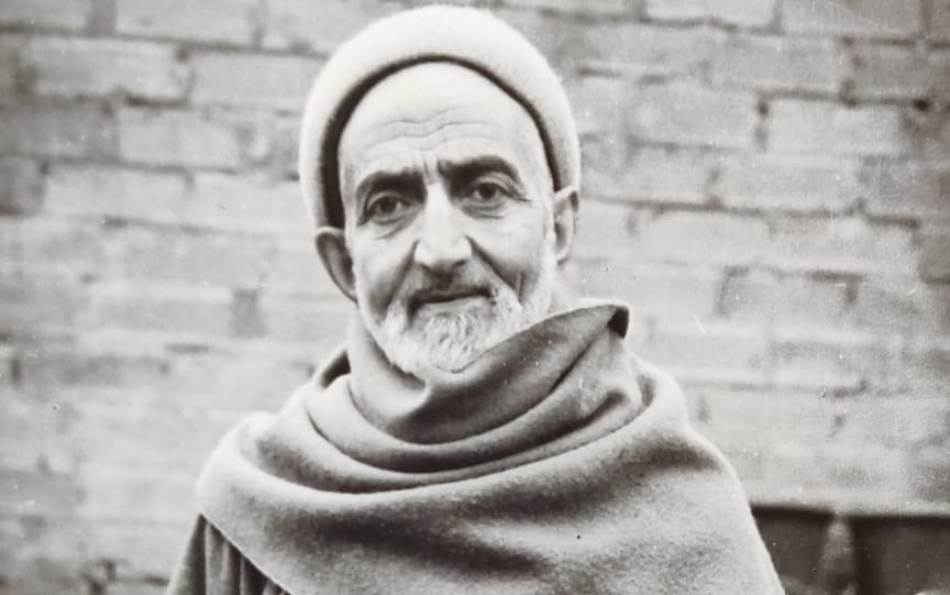

Khwaja Muhammad Amin Darab: between rupture and continuity

Born: 1308AH/ 1890-91CE

Died: 1979 CE

Buried: Khywan, Narwara

Father: Khwaja Nur-ud Din Drabu

The first half of the twentieth century marks a steady eclipse of Persian in Kashmir, after its prominence as the language of the court, religion, literature, histography and elite culture for more than five centuries. In this world of steady decline, Khwaja Muhammad Amin with the takhalus (penname) Darab emerges as one of the last transmitters of traditional Muslim learning, grounded in Persian adab (literature).

Born in Narwara, Srinagar, Darab belonged to a prominent Kashmiri family of traders and landowners: the Drabus. His father, Khwaja Nur-ud Din, aside from being a trader in the city, was also well versed in Persian adab, as is evident from the qitah-i-tarikh (chronogram) he wrote in Persian on the birth of Darab. Moulvi Ibrahim in his short sketch on the life of Darab, postulates that the father must have also served as the first tutor of his son. This is a tradition which we also observe in other literary families of Srinagar, especially in the nineteenth century.

The last quarter of the nineteenth century marks a transition in Kashmiri society, with the colonial education system of teaching in English making headway in the city, especially through schools run by Christian Missionaries. To counter this, Mirwaiz Rasool Shah (d. 1909) opened a madrassa, which in the early part of the twentieth century took the shape of a High School.

Though the Darbu family had emerged as strong followers of the Mirwaiz family and would remain so, we have no account of Darab getting enrolled in any school. His education was based on the traditional maktab system operating in the city, though from his letters it emerges that he also acquired a working knowledge of English.

The maktab-based education with its deep focus on religious orthodoxy and morality finds resonance in Darab’s writing both in prose as well as poetry. This is reflected in his naat’s and manqabats which speak of his spiritual yearnings and worldview. These devotional poems figure not only in praise of Prophet Muhammad but also Sufi saints of Kashmir, particularly the Suharwardi master, Shaykh Hamza Makhdum (d. 1576), popularly known as Sultan-ul-Arifinin. Both in his devotional poetry as well as in his ghazals, Darab’s imagery and metaphors are traditional; his themes are old and classical. Overall his poetry reflects a continuation of the nineteenth-century trend in the Persian poetry of Kashmir yet stands far removed from the heydays of its development in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

While Darab seeks to imitate past Kashmiri masters, the likes of Mulla Tahir Ghani (Ghani Kashmiri), Mulla Abdul Hakim Sateh, and also finds inspiration from great literary figures of the twentieth century such as Shaykh Muhammad Iqbal, yet nowhere in his works does he engage with the idea of modernity as it developed in twentieth-century Persian poetry: “the new poetry’- (shi’r -inau). Coincidentally, Darab’s adopted pen name is the same as the surname of a famous Persianate poet of Kashmir, Mirza Darab Beg Joya (d. 1706CE), though some writers assume Darab to be the original form of Drabu family name.

Darab’s lifelong interest in Kashmir’s contribution to Persian adab is best highlighted in his meticulous documentation of the works of one of Kashmir’s greatest Persianate poets, Ghani Kashmiri. Published in 1980 under the title Diwan-i Ghani, the volume reflects Darab’s desire to preserve and promote this historical link between Kashmir the land and Persian the language. He also worked on preparing an edition of Baba Dawood Khakhi’s, Qasidayah Lamiyah, which unfortunately remained unrealized. Aside from his poetry, Darab was also a respected calligrapher, some of his handwritten rukas show his command in the Nastaliq script.

This exhibition is also an invitation to individuals and families across the geography to preserve and share their family archives. We at INTACH Kashmir are committed to celebrating our cherished common heritage with the community at large.

(Former DG of Tourism Jammu and Kashmir, the author heads the INTACH Jammu and Kashmir chapter.)