Demolition of numerous “illegal” seasonal hutments of the nomadic tribes across Kashmir and Jammu by the authorities has triggered an outcry in Kashmir and a call for the implementation of Central Forest Rights Act that acknowledges the symbiotic relationship between Gujjars and the jungle, reports Umar Mukhtar

On November 9, when Abdul Aziz Khatana, 38, had just reached Aru road in Pahalgam where he works as a labourer for a contractor, his phone buzzed. It was his wife who asked him to get back to his home at Lidroo village.

“Some people have demolished our hutment (Kotha),” she told him over the phone.

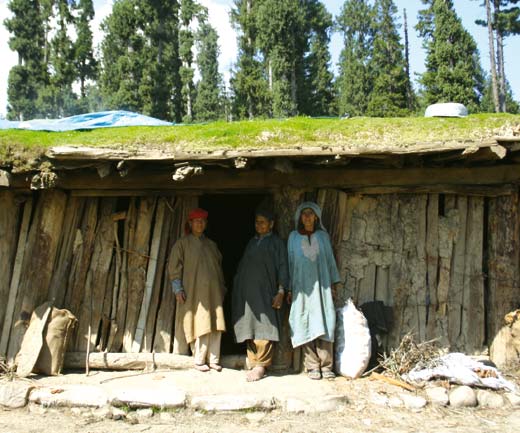

Khatana left the work midway and headed back home. He saw the structure had been razed to the ground. “This kotha was made by my grandparents,” he said.

Table: Gujjars and Bakarwals in J&K, 2011

Total Muslim %

Gujjar 9,80,654 9,73,946 99.32

Bakarwal 1,13,198 1,11,681 98.66

Officials from the Pahalgam Development Authority (PDA), the Revenue Department, and the Forest Department had started dismantling the structures citing encroachment as the reason. Khatana said that around 500 people along with the police personnel had visited the site to dismantle the hutments.

These hutments are relatively at higher altitudes and are used by the people of the Gujjar tribe mostly in the summers. As the winters come, they either retreat to their houses in the plains or migrate to the Jammu region, mostly to Rajouri and Poonch.

It takes weeks of work and around one lakh rupees to construct one single Kotha, said Khatana.

“I was living there with my six family members and had moved just days before to another house as the winter set in,” he said. “But our livestock was still there.”

Now Khatana has been offered space by his neighbours for his livestock.

There are almost 30 kothas in the Lidroo village most of whom were dismantled that day. In the nearby vicinity, officials said they had retrieved land from “illegal occupants.” These include Mamal, Khelan, Movera and Rangward. In these areas, mostly nomads make temporary hutments for the summers.

Khatana claimed that he had not received prior notice from the authorities. But in other places, the authorities had issued notices in various areas to the people asking them to clear the land which, as per the authorities, had been illegally occupied.

The notice reads: “You have illegally occupied the land of the forest department and also erected an embankment. In this connection, you are informed to raze these illegal structures within seven days.”

Such notices were also served in the upper reaches of the Tral that is mostly inhabited by the tribal people. This situation has created a fear psychosis among the tribals and nomads.

Fear Psychosis

Mohamad Yousuf Gorse, a resident of Lidroo, now fears any movement in his locality. “I know I can be homeless anytime,” Gorse said. “I have a family of seven people where will I go now.”

After the news broke that hutments were being destroyed in Pahalgam, people from the cross-section of the society visited the place. There were politicians, community leaders, and concerned citizens. One major factor was the demolitions took place at a time when the winters have already set in.

Among them was Talib Hussain, a leader of the Gujjar and Bakerwal community.

“As I reached there the villagers fled their homes, they thought some team has come to dismantle their homes again,” Hussain said. “Such is the fear among the people. They even fear people from their own tribe now.”

In the notice, members of the tribal population have been warned to evacuate as soon as possible or the forest department will have the authority to demolish “illegal” constructions.

Zahid Parwaz, president of the Jammu and Kashmir Gujjar Bakarwal Youth Welfare Conference said it is ironical to say that the government has retrieved land. “Gujjars and other nomad tribes have been living in the forests for ages. Since when they became the illegal occupants,” he wondered.

“This statement is totally misleading and has the potential to create animosity among the people, as people would think we have really usurped these lands”. Parwaz said that they are the first line of defence to protect the environment. “When there are forest fires who is there at such places who douse those fires?. We have always been living in a symbiotic relationship with these forests,” he said, adding this was for the first time that this development had taken place in the Kashmir region. “The same thing is happening for a long time in Jammu region”.

Jammu Issues

“It is unfortunate that a perception was created in Jammu region that if Gujjar and Bakerwals are allowed to avail forest rights, it will result in a demographic change in the non-Muslim majority districts of Jammu, Sambha, Kathua, and Udhampur,” said Talib Hussain.

He said that in Kathua in 2016, a severed head of a cow was thrown into the premises of Haji Alam Din’s house. “Then the right-wing people along with the police attacked him,” Hussain said. “This all is done under a proper watch to harass the tribal people and to usurp their lands.”

According to Hussain, a narrative has been built that tribal people are land grabbers, forest encroachers and cattle smugglers. “This is helping those who oppose the Forest Rights Act 2006 (FRA) in the Union Territory of Jammu and Kashmir because this has influenced public perception,” he said, adding that after the migration of the tribal people in winters from Kashmir in last year many nomad families were not allowed to build kothas in Jammu region that was dismantled earlier.

The Seasonal Nomads

Forests across Jammu and Kashmir have traditionally been frequented by a host of groups for various economic reasons. In Kashmir, Pouhal, the traditional sheepherder assembles the flocks of the peasantry and takes them grazing to the mountains for most of the summer. In revenue records, they are known as Chopans. Earlier, the same was true with other cattle, mostly the bulls. The arrival of the tractor has halted this process, however.

But the major population that would frequent the forests has historically remained like those of Gujjars and Bakerwals. “Bakerwals are also Gujjars who are exclusively into goat-herding,” Javid Rahi, one of the Gujjar scholars and activists, said. “Gujjars fall in three categories – one that, off late, is into farming; the second that is into buffalo rearing and are completely into milk supply and finally the class of Gujjars who are sheepherders.”

With an identical profession, they are the major herd-owners in Jammu and Kashmir. They are spread across all districts of Jammu and Kashmir with a concentration in Jammu districts. They move between the pastures of Kashmir and Jammu strictly following the weather situation. In winter, they are mostly found in the forests of Jammu region and early summer they are back to Kashmir. Their profession is directly linked to the economy of Jammu and Kashmir as the milk, mutton, beef and wool comes from their activity.

Rahi said the Gujjar and Bakerwal populations are into various kinds of migrations. There are even classes within them. “One class of migrant Gujjars are those having a home and a right to a dhok up in meadows,” Rahi said. “Second class comprises those migrants who own a home but graze their herds on a pasture that is sub-let to them by the original allottee. The third class comprises of the Gujjars who lack a home and a pasture.” Around 20 per cent of the population Rahi believes, could belong to the third category.

Over the years, however, a tradition has emerged that the peasants in the plains of Jammu would offer their small patches of land for these migrant Gujjar herders either on some small rent or simply to enrich their lands with manure so that they could produce organic crops. This tradition has started getting hurt in recent years. A section of these Gujjars now moves to Punjab where the farmers are extending the same offer because burning the residual paddy stubble is banned. In fact, the rice residue is free in Punjab and the Gujars invest in transport to feed their cattle in Jammu.

Gujjars and Bakerwals fall in the Scheduled Tribes and they are a substantial number. As per the 2011 census, the ST population in Jammu and Kashmir is 14.9 lakh – 9.8 lakh are Gujjars and 1.1 lakh Bakarwals. They all are Muslims.

These tribes were facing tensions already because of the situation. Security forces have already restricted their entry into a number of meadows in north Kashmir for security reasons. After the 1999 war between India and Pakistan, these herders faced additional restrictions in the Ladakh region.

There has not been any conflict between the governance structures with the Gujjars and Bakerwals for most of the recent history. However, the conflict has started becoming a front-page every time community leaders or the forest officials enter the forests. In the last few years, a new narrative has emerged that the people dwelling in the forests are encroaching upon the green belts and possibly triggering demographic change.

When the Government of India legislated the Forest Act, Jammu and Kashmir was not reporting any special issue with regard to the forest use by the erstwhile state’s ST population.

Forest Rights Act 2006 (FRA)

The Forest Rights Act of 2006 recognises the rights of Forest Dwelling Scheduled Tribes (FDST), and Other Traditional Forest Dwellers (OTFD), to forest lands and produce except for timber.

The law enshrines four main rights of the forest dwellers:

Every FDST and OTFD family gets ownership rights to up to 79 kanals, or 4 hectares, of the forestland that they cultivated as of December 13, 2005. Even if this land that is being cultivated by the forest dwellers is entered as forest land on revenue records, it doesn’t matter. The ownership of 79 kanals of this forest land which is under cultivation of a family will have to be transferred to that family. They can’t be evicted out of that land.

The FDST and OTFD have the right to extract forest products other than timber. They have grazing rights to their forest lands, and they have the right to move on pastoral routes.

The FDST and OTFD populations have the “right to protect, regenerate or conserve or manage any community forest resource” traditionally in their use.

The Forest Rights Act covers every Scheduled Tribe person who lives on forest land and whose livelihood is dependent on forests, as the Gujjar and Bakerwal community is. They have to be living on forest land on December 13, 2005. It also applies to any non-Scheduled Tribe person or community living on forest land for three generations or 75 years until December 13, 2005.

After 2019

But after Article 370 was read down, the Government of India passed the Jammu and Kashmir Reorganisation Act in the parliament. As per this Act, 153 Acts of the former state of Jammu and Kashmir were repealed, 166 Acts were retained from the former state and 106 new laws were applied to Jammu and Kashmir. Among the new laws applied is FRA.

Tribal leaders and activists say that despite the FRA now being applicable to Jammu and Kashmir, it is yet to be implemented.

“If central laws are directly applicable in Jammu and Kashmir, then why is the Forest Rights Act not being implemented here?” asked Zahid Parwaz.

However, Parwaz sees the latest development in Kashmir through a different prism. He said that after the amendment of land laws was made, to ensure the spaces for outsiders, the government is doing all this. “This is how demography will be changed. We were the soft target and they proceeded against us first,” Parwaz said. He further said that earlier in the Kashmir region tribals had never felt the sense of insecurity.

A Court Case

Officials, however, insist that the presumed objectives attributed to the demolitions are far-fetched. They said they were acting to implement the directions passed by a Division Bench on a Public Interest Litigation (PIL) titled PIL 23/2017 Save Animal value Environment V/S UT of Jammu and Kashmir (regarding encroachment of Forest Land).

A letter, in possession of Kashmir Life, written by the Additional Deputy Commissioner Baramulla to a field revenue officer reads “….the Divisional Commissioner Kashmir in the meeting held on 21-10-2020 and 02-11-2020 has directed that close coordination among the departments of Forest, Revenue and Police be ensured for complete eviction of forest land from its illegal encroachers. To effect these anti-encroachments drives, you are requested to accord full cooperation to the officers of the Forest Department falling within your territorial jurisdiction, as and when needed, so that the encroachments from the forest land are removed without any hindrance.”

However, there is no detail available about who identified the Gujjar hutments – being built for special purposes and some as old as more than 100 years – as “illegal”. There is also no clarity that if such an important PIL was being heard by the High Court, why the department of forests did not submit the details after consulting with the STs of Jammu and Kashmir. All the demolitions, mostly in Jammu, were a regular process. It created sort of a crisis only after the demolition drive got into Kashmir.

Reactions

The political parties also expressed their concern over the issues. Leaders from many political parties including PDP president Mehbooba Mufti and NC’s Gujjar leader Mian Altaf Ahmad visited the sites of the dismantling of the Gujjar and Bakerwal structures in Pahalgam.

The government, she said, that is trying to hound the backward communities of Jammu and Kashmir. She added that the actual displacement of Kashmiris has started most unfortunately with the forcible eviction of ‘Gujjars and Bakerwals’ from their pastures.

“The Gujjars have been using log and mud sheds in pasture lands since times immemorial during the grazing season. They are part of the forest and our environment. Sadly, a drive has been launched to demolish these structures which they use as temporary shelters during summers,” asked the former Chief Minister. “Their families have been harassed, using strong-arm methods. Does this mean that these nomadic tribes can no longer go to pastures? Is that Part 2 of this displacement scheme? Who do they intend to sell the forest land to?”.

Mehbooba asserted that as already reported in the media, the government has requisitioned 24 thousand kanals of forest land for setting up industries there. According to Mehbooba, that will be a disaster for the forests and the environment.

“While hundreds of new provisions of laws have been introduced without any consultation with local stakeholders and mostly not beneficial to us, the few laws that could result in some benefit to the residents of the state are not being implemented. One of them is the Forest Act of 2006, which could provide a legal framework for Gujjar and Bakarwal rights on Forest land. Similarly, while lands are being requisitioned in bulk, the Central land Acquisition Act is not being implemented, so that the landholders of J&K do not receive any benefit therefrom,” Mehbooba said.

Table: Gujars in Jammu and Kashmir

Year No

1891 2,15,796

1901 2,86,109

1911 3,28,003

1921 3,62,107

1931 4,02,781

1941 3,81,457

The PDP chief added that the illegal and immoral assault on Gujjar and Bakarwal population is a wake-up call for all of us and that the dislocation has begun with them and it will hit all of us.

“I call upon the government to immediately stop this illegal encroachment and harassment of a marginalized and most vulnerable community, who will do everything to peacefully resist this and defend their rights,” she said.

Response Finally

After the issue got highlighted and activists from the community expressed anger and resentment, Chief Secretary, B V R Subrahmanyam chaired a meeting to review the implementation of the Scheduled Tribes and Other Traditional Forest Dwellers (Recognition of Forest Rights) Act, 2006, and Rules in Jammu and Kashmir which have been made applicable post-enactment of the Jammu and Kashmir Reorganization Act, 2019.

“We had to make a series of efforts to convey the administration that the central forest act is actually in vogue now in Jammu and Kashmir,” one Gujjar leader said. “We knew the administration was responding coolly to the implementation of the law.” Some within the community allege that the Division Bench order was used for demolitions so that the Gujjars and Bakerwals cannot later claim they ever lived in these forests as the forest law requires for conferring the rights.

In the meeting, it was decided that the ‘survey of claimants’ by the Forest Rights Committees for assessing the nature and extent of rights being claimed at village level be completed by January 15, 2021, for their further submission to the respective Sub-Divisional Committees. The Sub-Divisional Committees shall complete the process of scrutiny of claims and preparation of ‘record of forest rights’ by or before January 31, 2021. Similarly, the District Level Committees shall consider and approve the record and grant forest rights by March 1, 2021.

It was revealed that under the Act, the forest-dwelling scheduled tribes and other traditional forest dwellers will be provided with the rights over forest land for the purpose of habitation or self-cultivation/livelihood; ownership, access to collect, use, and dispose of minor forest produce, and entitlement to seasonal resources among others. However, the rights conferred under this Act shall be heritable but not alienable or transferrable.

The Act further provides that on the recommendation of Gram Sabha, forest land up to one hectare can be diverted for the purpose of developing government facilities including schools, hospitals, minor water bodies, rainwater harvesting structures, minor irrigation canals, vocational training centres, non-conventional sources of energy, roads, etc.

The Act also empowers the holders of forest rights, and Gram Sabhas to protect the wildlife, forest, biodiversity, catchment areas, water sources, and other ecologically sensitive areas, besides ensuring that the habitat of forest-dwelling STs and other traditional forest dwellers are preserved from any form of destructive practices affecting their cultural and natural heritage.

The Chief Secretary impressed upon the Forest department to immediately constitute the 4-tier committees including- State Level Monitoring Committee, District Level Committee, Sub-Divisional Level Committee, and Forest Rights Committee; to implement the Scheduled Tribes and Other Traditional Forest Dwellers (Recognition of Forest Rights) Act 2006 in Jammu and Kashmir.

For a periodic review of the process and procedures associated with the Forest Rights Act and Rules, the Forest department was asked to devise a suitable review mechanism along with monitoring formats.

New Issues

It would look strange that the Governor’s administration will continue demolitions on one side and at the same time continue identifying the people who have traditionally been living in the forests for implementation of the new central law. Community leaders said they are heading towards the new crisis. Under the new law, that government will constitute village committees that will receive the claims by the Gujjars. The applicants will have to prove that they were in the forests from a particular date. Once their claim is approved by the village committee, then only it will go to the net level and the approval will come at the third level of the process.

“What about the families whose Dhoks were demolished a year back without any notice,” one Gujjar leader said. “The rains and the snow have already erased all the proofs from those locations.”