After a series of failures in various laboratories across the globe, Dr Khalid Shah, a young Kashmir scientist, currently, a professor at the Harvard Medical School, led a team of researchers to devise a technology to treat brain tumours. Using a gene-editing technique, the group of scientists used live cancer cells and repurposed them to become tumour-killing agents and it succeeded. Humaira Nabi reports the cutting-edge development in science that will help humankind manage one of the most virulent cancers

As Kashmir reels under intense cold, thousands of miles away a Kashmiri scientist is snowed under with interviews, calls, e-mails and texts, after he along with his team got successful in developing a cancer-killing vaccine. He has been chasing the project almost for a decade. Employing a novel method for converting cancer cells into potent, anti-cancer agents, Dr Khalid Shah, now a Professor at the prestigious Harvard Medical School and Vice Chairman, of the Department of Neurosurgery, at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston is hitting headlines across the globe.

While many laboratories have been working on cancer vaccinations, but the efficacy of diverse approaches has so far been limited. However, Dr Khalid and his team’s technique proved that dual-action cell therapy was safe, practical, and efficacious in the models, indicating a path toward therapy. The breakthrough is seen as a game changer in the treatment of the world’s most lethal disease.

Dr Khalid’s work focuses on developing cell-based gene-edited and engineered therapies for cancer.

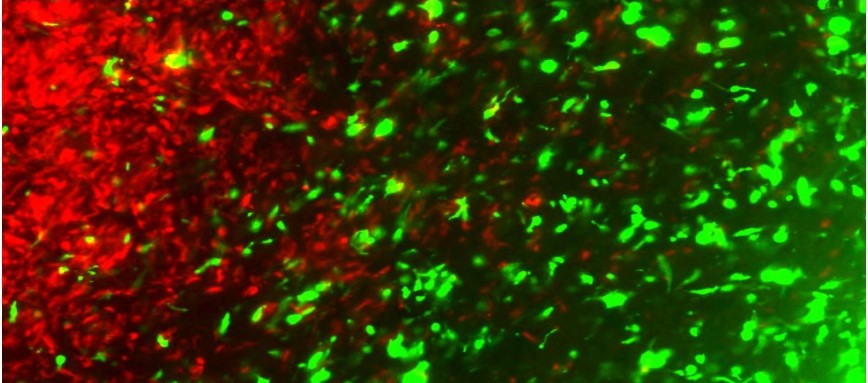

In their recent findings, the team of scientists led by Khalid have transformed living tumour cells into a treatment. Using the gene editing technology CRISPR-Cas9, they engineered living tumour cells and repurposed them to become tumour cell killing agents – an age-old dictum of setting a thief to kill a thief.

CRISPR-Cas9 is the most exciting genome editing technique that is widely used by genetic scientists across the world because it is fast, cheap and accurate. In 2020, American scientist Jennifer A Doudna and French scientist Emmanuelle Charpentier, bagged the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in recognition of their discovery of CRISPR-Cas9 gene scissors, now the greatest weapon in genetic technology. Gene editing is found as part of bacteria’s immune system when it was attacked by pathogens, mostly viruses. “When infected with viruses, bacteria capture small pieces of the virus’s DNA and insert them into their own DNA in a particular pattern to create segments known as CRISPR arrays, that allows the bacteria to “remember” the viruses,” open source information suggests. “If the viruses attack again, the bacteria produce RNA segments from the CRISPR arrays that recognise and attach to specific regions of the viruses’ DNA. The bacteria then use Cas9 or a similar enzyme to cut the DNA apart, which disables the virus.”

Gene Editing

The engineered tumour cells were designed to express factors that would make them easy for the immune system to spot, tag, and remember, priming the immune system for a long-term anti-tumour response. The team tested their repurposed CRISPR-enhanced and reverse-engineered therapeutic tumour cells (ThTC) in different mice strains including the one that bore bone marrow, liver, and thymus cells derived from humans, mimicking the human immune microenvironment. Dr Khalid along with his team also built a two-layered safety switch into the cancer cell, which, when activated, eradicates ThTCs if needed.

“Over the last decade or so I have been focusing on figuring out something that is new,” Dr Shah told the Kashmir Life’s Science Talks. “One of the things we looked at a few years ago was whether we could use cancer cells to kill cancer cells. Although inactivated cancer cells have been used as vaccines previously, however, the results have not been particularly successful. While vaccination works well for diseases such as smallpox or Covid19, it is critical for cancer that the remaining cells post-surgery in solid tumours be killed first.”

Dr Shah explained his successful experimentation. “We sought to maintain some of the natural qualities of cancer cells, such as their ability to travel long distances and present neo-antigens while arming them with weapons such as cell killing agents, immunotherapeutic agents, and safety switches,” Dr Shah said. “So, we did it while keeping a couple of the cell’s oriental qualities in mind. Gene editing and gene engineering were used to introduce three or four novel features, which were then tested in various models.”

Disease Fighting Disease

Lady Montagu from England, whose husband was part of the military in Turkey in the seventeenth century, learned from Turkish caregivers that smallpox can be prevented by giving a small dose of smallpox. Therefore, she purposely infected her own three-year-old daughter in England with a minuscule quantity of smallpox, effectively immunising the kid almost 75 years before Edward Jenner discovered the vaccine. This concept of disease-fighting disease has inspired Dr Khalid’s novel approach to cancer treatment.

“A number of diseases including measles, mumps and smallpox were cured in the eighteenth and nineteenth century by this concept of ‘fighting a disease with a disease’. When I proposed this method for cancer treatment to my team, they felt I was crazy,” Dr Khalid said. “But my perseverance prevailed. And I began with a simple idea of taking a patient’s cells and converting them into cancer killers.”

Repurposing Tumour Cells

Dr Khalid and his colleagues repurposed a patient’s own tumour cell and added an activatable kill switch. The activatable kill switch was introduced in order to have complete control over the cell. Because cancer cells are highly good at concealing from immune cells, an immunological modulator chemical was also included. This helped them not only to kill the cancerous cells but also to bring immune cells to the tumour location, preventing tumour re-growth.

The researchers now had something amazing and one-of-a-kind in their hands: a cancer cell that would kill its sister cell, an activatable kill switch that would kill this repurposed cell and a cell that would influence the immune system. So it was one cell with three different bullets. The process was followed by a multidisciplinary approach where, nanotechnology, gene manipulation and tumour biology were consorted to mimic diseases in models like mice.

The team developed and tested two techniques to harness the power of cancer cells. The “off the shelf” technique used pre-engineered tumour cells that would need to be matched to a patient’s HLA phenotype (essentially, a person’s immune fingerprint). The “autologous” approach used CRISPR technology to edit the genome of a patient’s cancer cells and insert therapeutic molecules. These cells could then be transferred back into the patient.

Disruptive Dozen

Dr Khalid’s project was chased by the media for a very long time. It even featured in the sixth annual event Disruptive Dozen where his work was regarded as having “the greatest potential to impact health care in the next few years.” The featured research has acknowledged his team’s success in “developing experimental models to understand basic cancer biology and therapeutic cell types for cancer” and the relevant studies have already been published in a number of very high-impact journals like Nature Neuroscience, Cell, Science, PNAS, Nature Reviews Cancer, JNCI, JAMA Oncology, Science and Lancet Oncology.

Disease Hit Home

In the midst of his research at Harvard, Dr Khalid had to fly home after his father in Srinagar was diagnosed with a brain tumour. For weeks, he remained busy attending to his father at SKIMS. Ghulam Mustafa Shah, 70, lost his battle with life on December 20, 2020. It was a highly aggressive brain tumour that failed to be managed for eight weeks after the disease was diagnosed.

“Since I started working as a researcher, I have been very connected with finding treatment for cancer, especially brain tumours,” Dr Khalid said. “When my father got diagnosed with the disease, it felt very ironic. I had never thought the disease would hit home the way it did. While my father was being treated for the disease, I stayed with him.”

The period goaded Dr Khalid to address this further and strengthened his motivation to work harder, and think out of the box.

“My father would always tell me to do something meaningful. That teaching has stayed with me as a guiding light. I hope that I will keep answering the question that, ‘if I have made a difference?’ for years to come.”

Gut Health: The New Focus

While researchers have suggested that the gut microbiome may play a critical role in immune system function, Dr Khalid believes that for the next years, a lot of emphases will be on the influence of gut health on cancer.

“We are gradually realising that our gut microbiome is the key to disease,” Dr Khalid, perhaps the first Kashmiri professor at the Harvard Medical School, said. “While we learned this from Hakeems a long time ago, we are now finding in cancer therapy that there are specific bacteria in our gut that have the potential to drive immunotherapy. As immunotherapy therapy works in some individuals but not for others and we are now learning that it could be due to a specific set of bacteria. So, I believe diet and fitness along with novel therapies is going to be the focus of cancer research for the next 10 years.”

FDA approval

Dr Khalid along with his team has done most of the advanced preclinical studies and is now seeking funds as the next step. This will be followed by reaching out to the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to seek approval for phase one trials in patients.

“It is important to understand our therapeutic is not a pill that we can make millions of copies and make available to patients,” explained Dr Khalid. “This is more of a personalised medicine and we have to use tumour cells from the patient’s gene, added a modified gene and give it back to them. Hopefully, in the next two to three years we will be able to reach the clinical trial stage.”

Dr Khalid currently holds positions on numerous councils, advisory and editorial boards in the fields of Cell therapy and Oncology. He has presented his findings for more than 300 academic seminars worldwide and in recent years has given various keynote lectures on the Innovation and Translation of biological therapies. More recently he has given a TED talk to share his ideas and findings. Dr Khalid currently holds numerous patents and he has founded two biotech companies whose main objective is the clinical translation of therapeutic cells in cancer patients.

Game Changing Technique

Most of the medicine reach the organs through blood. This is true with chemotherapy as well. However, making the medicine reach brain is one of the most challenging part of the treatment because of the brain blood barrier. In Dr Khalid Shah’s finding, the repurposed or the turncoat cancer cells have smoothly moved this barrier. This is being seen as a major advantage. At the same time, it is being said that if this therapy is possible in cases of brain tumours, it eventually would pave way for managing other malignancies, even though cancer exhibits its own diversity.

Dr Shah’s laboratory has experimented with the breast cancer as 15 to 30 per cent of metastatic breast cancer have brain metastasis. “Because breast cancer can metastasize to the brain in numerous patterns, the researchers spent three years building mouse models to reflect the range and complexity of human disease,” a piece of information about the research posted by the laboratory on its website said. “One mouse mimics metastasis that takes the form of a solid tumour in the middle of the brain (macro-metastasis), the second mimics a more scattered metastasis (perivascular niche micro-metastasis), and the third mimics one that appears in the back of the brain (leptomeningeal metastases). Armed with these models, they could more accurately determine the efficacy of the new therapeutic molecule.”

Cancer cells, it may be recalled here, have a self-homing ability, which means they move within the body to locate tumours. This capacity makes these cells the most efficient courier of delivering

Longing for home

Quoting a rough translation of one of Allama Iqbal’s couplets, Dr Khalid said, “a branch that is not connected to its roots, won’t witness a spring.”

“I normally don’t look at where I am but I always think where I came from,” Dr Khalid said. “I think about Kashmir every day. I think about the people there, my friends, and my family on a day-to-day basis. That is what drives me as well.”

“I think we have brilliant people here in Kashmir,” Dr Khalid said, when asked about Kashmir’s next generation and how they can be encouraged to get into science and high-end research. “I would only advise them to pick up their careers early on. Whatever you want to do, you have all the calibre. But that would not help if you are indecisive. Take a decision, pick up your drive and go for it.” He asserted: “I would be delighted to share my knowledge and mentor those in need.”