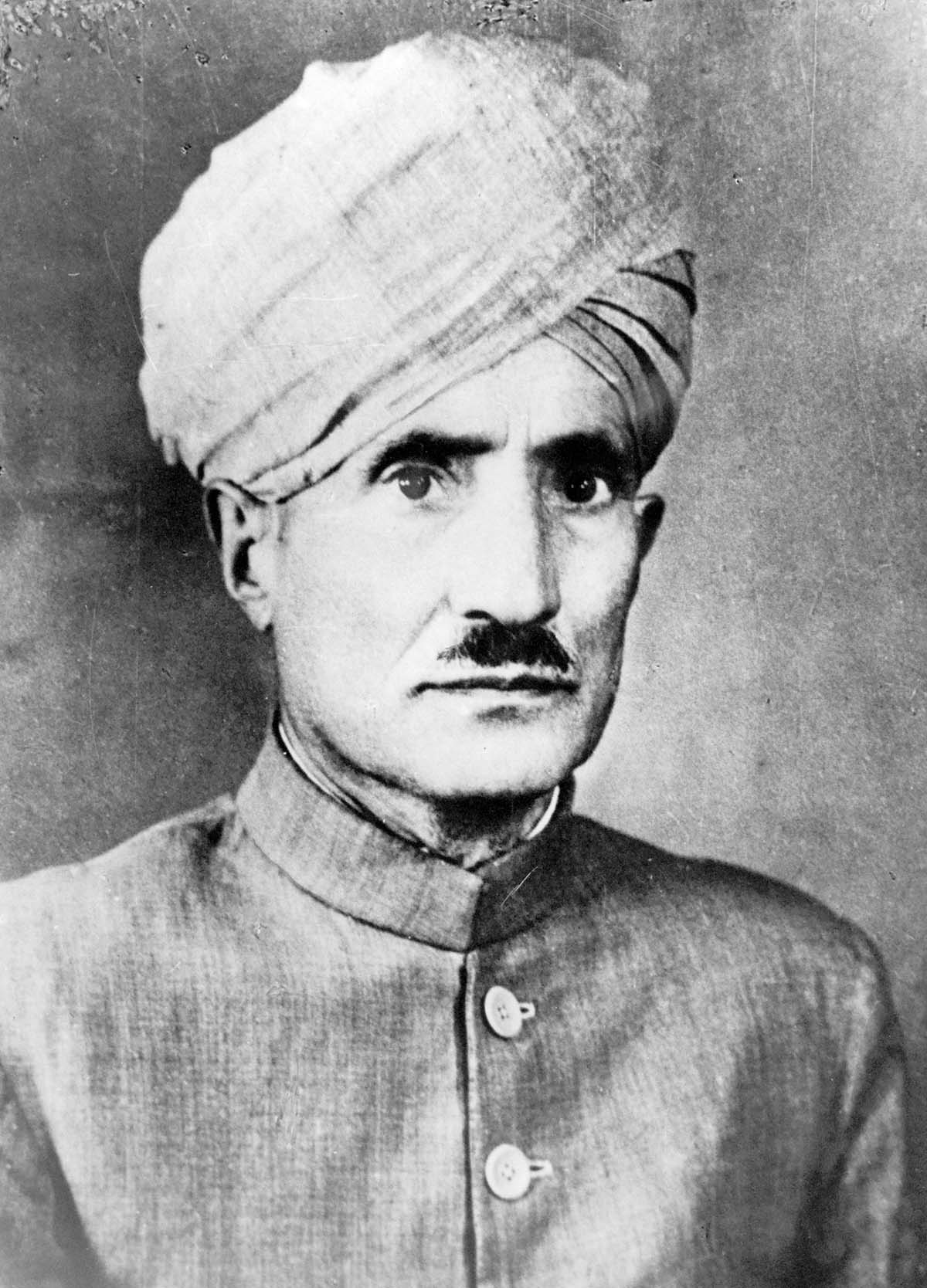

Perhaps the oldest surviving pensioner, Abdul Rashid Khan studied forestry in the UK when Hari Singh was still Kashmir’s proud owner. On the way home, he was caught in partition, massacres but had a providential escape. As Kashmir started ruling the Vale, he faced a coerced migration and had to work in PaK for seven years. Currently unwell, Kashmir’s first Muslim Chief Conservator shared his life story with Masood Hussain

We are basically Mirs. Our ancestor was one of the followers of Mir Syed Ali Hamadani. My great-grandfather, Abdul Aziz Mir, was a religious man. He died at about 100 years of age in 1917. His son, my grandfather, joined the business at the age of 15. With the help of Goni Khan, his Mamu, who later became his father-in-law as well, helped him to establish and our family got the Khan surname.

In 1920s, every family in Kashmir wanted to have a male child as the daughters were disliked because of social and economic conditions. It was a burden to bear a girl’s wedding and dowry. My businessman grandfather Ghulam Qadir Khan had four daughters and he was praying for a son. He went to Makdoom Sahab and had a 41-day Minnat (votive prayer) for a son, thus my father, Ghulam Rasool Khan was born in 1907 at Bohri Kadal.

Feeling lucky, my grandfather gave him education and was desperate to see him settled. At the age of 11 years, he was married. It was a child marriage. He slept in baraat. My mother was 12 years of age. He passed his matriculation in March 1923 at the age of sixteen and a month later, I was born.

My father continued his studies. He joined S P College and when he was in BA-III, my younger sister, Mrs Andrabi was born. She was 22 months younger to me. She died in early 2017. Both of us were brought up together.

My father graduated at a time when Muslims were very rare in education and Pandits dominated every field. That year, 13 boys appeared for graduation, but my father was the only one who passed. At that time Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah was studying at Peshawar. He did his BSc but got compartment in a subject and couldn’t get a full degree.

Since there were more non-state subjects running the government, Maharaja Hari Singh floated a scholarship for professional training in engineering, medical, sericulture, public administration, agriculture, and horticulture. My father was selected for Civil Engineering in Harvard, America in 1927. Out of 10 people, he was the only Muslim. The other who was selected for engineering was Vasudev Zadoo, a Kashmiri Pandit. Zadoo was M Sc Chemistry and had taught my father at S P College. Maharaja gave the scholarship to the teacher and his student. My father was 20 years old and a father of two kids.

For three years, we were raised by our grandparents. An intelligent man, my father got honours in America, unlike his teacher. The honour is called Tau Beta Pi and is the oldest engineering honour for engineering students in American universities who have a history of academic achievement and commitment to personal and professional integrity. My father was first Kashmiri Muslim engineer who brought laurels from the US.

My father was the first Kashmiri to land in the US. His journey was interesting. He drove to Rawalpindi in a bus and then to Bombay by train and finally boarded a ship for three weeks. Because of sea turbulences, the ship sailed to the US in 40 days via Cape of Good Hope, Africa. He returned home in 1930.

When my father returned home, I was in the fourth primary. He was appointed as Assistant Engineer, and was transferred to Baramulla. In 1933, my younger brother, Nazir Ahmad Khan was born. A decade younger to me, he retired as Director Sports Kashmir.

I studied in Baramulla up to eighth class after which I joined Saint Joseph High School. I had spent only four months there that my father was transferred to Srinagar. I joined Government High School, Baghi Dilawar Khan (Fateh Kadal). After passing my matriculation in 1938, I joined SP College in science stream. In 1938, there was a facility of science in BA courses. Physics as a subject came to Kashmir in 1940s. I passed my medical FSC and joined Aligarh Muslim University in 1941 and completed my BSc (Botany, Zoology and Chemistry) in 1943. I did my MSc Zoology (specialising in Entomology) in 1945.

Then, there was much scope in forestry so my father wanted me to study it. My father got me admitted in England in forestry school in 1945, at his own expenses.

I reached Bombay and took a troop ship, HMS Britannia. Those were days when World War – II was over and soldiers were coming back to civilian lands. The ship was full of soldiers. I remember we were just ten or twenty students in that ship. The ship was a floating city with every facility – games, swimming pool, catering. We enjoyed a lot and after three weeks, we were in Liverpool. I took a train to Wales College. I studied forestry for two years.

With studies over, it was time to come home. It was August 1947. I boarded the luxury ship RMS Strathmore. We were sailing and still three days away from Bombay when independence was declared. We celebrated Pakistan day on August 14, 1947, on the ship. Without any animosity, we enjoyed raising Pakistan flag, and a day later, we unfurled the Indian flag as well.

On August 18, I landed in Bombay. I had to take a train to Rawalpindi. Communal trouble had started. My father had sent a telegram to a contact of ours in Bombay saying “Please keep him in Bombay, don’t allow him to come here”. But that wire never reached Bombay.

So I got on the train and when we reached Delhi it was chaos. The villages were up in flames; massacres taking place. It was a miraculous escape. But we still reached Rawalpindi and credit goes to Wahid. A Peshawar resident, he was also travelling from England. After he reached home, he wrote a letter to me saying that our train was the only one which was not attacked. Before that, there was a massacre on the train and the lucky part in our case was that on our train there were some army platoons of British Indian Army. So when the train started they immediately took an escort. While the train was chugging, we saw people coming with spears and swords from a distance. It was terrible to see villages burning. When we reached Lahore, the railway station was full of dead bodies which were lying on the platform. My relatives had given all hope but when I reached safely, they could not believe their eyes.

From Lahore, I drove to Rawalpindi. There, although the conditions were bad, but it was calm. Some tourists were coming to Kashmir, they booked a wagon and luckily there was one vacant seat and I reached home.

I reached Srinagar on August 18 August. By the end of the season, as I was strolling on the streets, I saw some Kashmir Motor Association (KMD) buses going to the airport. Those were the days when Sheikh Sahab was in Delhi pleading Pandit Nehru to send Army. They finally agreed.

Before that, there was Sher Bakra rivalry and Sheikh Abdullah used to threaten Moulvi Yousuf Shah saying: “I will kill them, crush them. My tanks would roll over them. I would trample them under my feet.” The tanks he talked of were these KMD buses for him.

These buses were eventually sent to the airport to fetch Indian Army. So what we saw was Indian army coming in these buses and on the roof of one of it was a Sikh soldier with a stun gun with unnerving eyes. They started the killing spree from Humhama, killed some villagers there, and then went on killing people till they reached Rambagh bridge.

At that time, we were living in Nawab Bazar. Those were the days when Hari Singh had purchased a personal aircraft and selected Damadar Wuder as the airport. The government was constructing the Aerodrome Road, which is now called the Airport Road. The land costs were Rs 5, a kanal. It was just a small silver plane maybe with four seats. But I remember the pilot and co-pilot were from Bombay. They would come through this rough road in a car.

Life was peaceful then, and the rule of law was strong. There was no violence, no thefts, and no intrigues. There was a sense of responsibility and accountability. Everybody was doing his job well.

I remember the incident of a former Maharani’s death. The Government Women’s College on M A Road was called Monde Palace (Widow’s palace) because widows of the royal family would stay there till death. When one Maharani died, the government declared 10-days official mourning. I was in Class IX. Students were also asked to wear the white turban for eight days. We did it too.

My memories of 1931, the Martyrs Day, are quite thin. I was studying in Ragunath Mandir School, Habbakadal, probably in the third or fourth primary. I remember teachers whispering and there was panic. The school closed an hour earlier. Roads were silent and the shops were closed. Nobody was on the streets except Dogra soldiers parading on the horses with spears in hands. My family was shocked when I reached home. My grandmother had watched from the attic the firing at Nawab Bazar Bridge.

Dogra rule had one rule that no Kashmiri to be recruited in Army – Kashmiri Pandit or a Muslim. Key posts were taken by Kashmiri Pandits. Muslims were decimated in education and that was the key factor that they were not employable.

Dogra rulers exhibited some principle. Maharaja never did any sort of sexual exploitation to Kashmiri women. He did not tolerate such things. Once, Maharaja of Kapoorthala came with a Muslim prostitute from Lahore. When Maharaja got the information, he gave him 24 hours ultimatum to leave.

You will not find any incident of exploitation by Dogra army of Kashmiri women unlike what is happening now.

It was during those primary school days that I saw Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah first. In my fourth primary, I had Mohammad Aslam Rafiqui as my classmate. Now, he is a doctor in Pakistan. His father Mohammad A R Rafiqui was a political worker. One day, Aslam invited me to his house saying some guests were coming to their home. After the school, I went to his home where I saw the entire family busy with preparations. Finally, Sheikh Sahab came. As he took a seat, I sat in front of him. A R Rafiqui served the Kehwa from a Samavor lying near and some snacks. Then, Sheikh Sahab started talking to me. He asked me about my school and studies. Then he gave me an advice: “Do not quit studying, ever.” That advice was always on my mind so I thought if he is an M Sc, I must also be an MSc.

My second meeting with Sheikh Sahab was when he took over the Chief Minister in 1975. He called a meeting of heads of the departments at Tourist Centre and I was Chief Conservative Forest. He was surprised to see a young man as holding this top position.

Kashmiris started their own ruler with absolute hooliganism, Gunda Raj. Sheikh was anti-Pakistan fearing his political career would be over. Mirwaiz was weak and so was Muslim Conference. We couldn’t listen to Radio Pakistan.

There was a gang called Khoftan Fakeer. These henchmen were paid Rs 30 according to the government, but Afzal Beigh, once jokingly said their actual pay is Rs 29 and 15 Annas of which one Anna is the ticket deduction.

Sheikh Abdullah started this culture and Bakshi took it to the next level. But Sheikh didn’t indulge into this directly. He used others to do his bidding.

I remember the salt famine. Kashmir would consume rock salt and it would come from Pakistan that stopped. Kashmiris didn’t know anything about the common salt. NC had some stock of rock salt and they put it on sale in their own shops.

Some of the young men who had studied outside would meet and discuss things over coffee without taking sides. We would meet in Khan Mohalla, where most residents were with police. Some of them were our distant relatives. One of them, once came to me saying my name has gone in police records and I would be arrested any time. This was scary. It was September 1948. I along with my classmate Hameedullah decided to visit Pakistan for a change. It did not require a permit. So we went to Pakistan via Delhi.

Some Kashmiri businessmen were in Kashmir House and were also going to Pakistan. But Deccan Airways had no seats available and the waiting list was of three weeks. Somehow, we got a chance to fly on September 8 or 10 in 1948. We had been there for five days that Qaid-e-Azam died. Soon, borders were sealed as tensions mounted. We were left in Pakistan till 1955.

There was a dearth of academicians in Pakistan so I got a lecturer’s post in Rawalpindi in a very famous college. I became Warden of the hostel. Then, I joined the Azad Kashmir Forest department and worked there for six years.

In Azad Kashmir, I heard of the Jammu massacres in which a lot of people were killed. I am told then Sheikh Sahab was asked about it, he said, ‘whatever is happening is right (because) they have never considered me as their leader’.

He finally sent Bakshi Sahab who controlled it but it was too late. Chowdhary Ghulam Abbas’s daughter was kidnapped and a Dogra married her. But then, he was faithful to her. Later, he went to Pakistan, embraced Islam and married her again.

In Azad Kashmir, I would see people who were involuntary migrants. Sheikh Abdullah had pushed them away. Most of them were intellectuals.

When I returned from England in 1947, Thakur Harnath Singh Pathodia, a Dogra was the Chief Conservator. He was impressed by my resume and immediately recommended my case for an appointment without waiting a day for a monthly package of Rs 240. It was rejected by his high-ups because “I was not their man”.

Finally, I joined government service in 1955. In 1988, I retired as Chief Conservative of the entire Jammu and Kashmir state. The post has been bifurcated now with Kashmir and Jammu having separate Chief Conservators.

Sheikh Sahab was personally honest but not his family. Begum Abdullah had collected three or four hundred Pashmina Shawls of very fine quality which had come as gifts. She sold them to Kashmir Arts Emporium as they needed it and got a very handsome amount. When Sheikh Abdullah started, he had nothing in hand and people contributed in making his house. Some gave him bricks; some gave stones; masons worked for free and people themselves made his house.

Bakshi was not honest but was a good administrator. I know a case when he had recommended a job for someone to then-Director Education whose name was Mukhtar. Bakhshi knew he would not appoint him without money. So he gave the person Rs 200 from his pocket to be paid to the officer for the job letter.

(Irtiza Rafiq processed this interview)