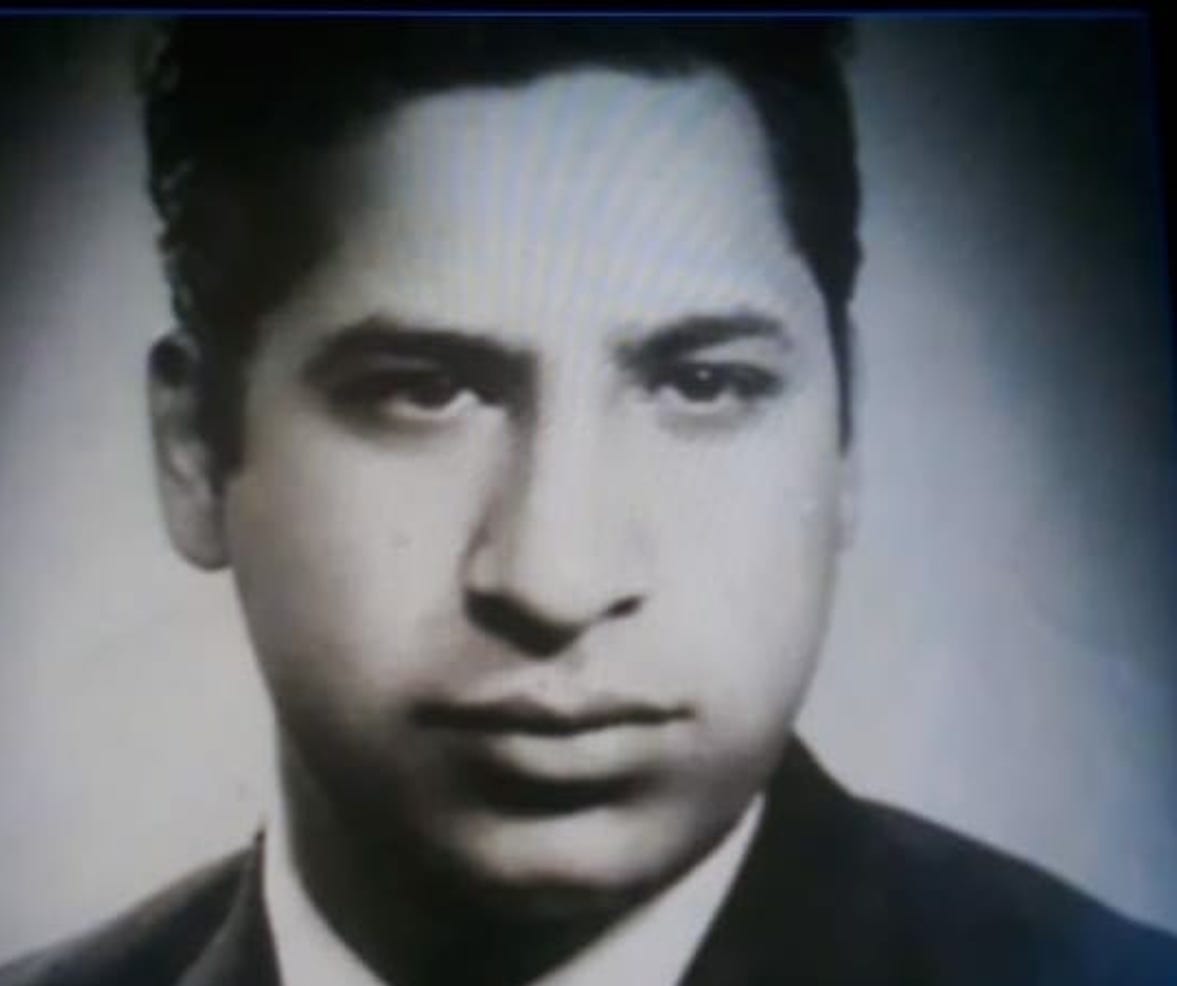

In the death of Ghulam Nabi Shaida, editor of Wadi ki Awaz, Kashmir has lost an upright editor who suffered for calling a spade, a spade, reports Khalid Bashir Gura

When the veteran journalist YousufJameel broke the sad news on social media about the death of Wadi Ki Awaz promoter and editor, Ghulam Nabi Shaida, condolences were uninterrupted. Shaida’s Partap Park office turned cold and silent. A few seemingly half-read books, empty chairs and desks stonily stared at anyone who unlocked the room. The staff members who had spent years with Shaidacouldn’t get themselves to enter the room.

On the freezing morning of January 19, people carried a coffin draped in black cloth with verses of the Quran inscribed in golden colour on it. They carried the coffin of one of Kashmir’s fearless voices from Rawalpora to a village in Pulwama.

Shaida, 74, was buried as per his last wish in his ancestral graveyard at Gouri Pora Barsoo. Unwell for a long time, two daughters survive Shaida. His wife had passed away in 2015.

Shaida was born on May 27, 1947. He got his primary education at his ancestral GouriPoravillage and passed his matriculation from Kakpora High School. Subsequently, he did his graduation from SP College, Srinagar. He completed post-graduation at Aligarh Muslim University. He has masters degrees in Urdu as well as in English literature.

Shaida began his journey in journalism as editor of the weekly Sahafi and later started his own bi-lingual daily, Wadi Ki Awaz in 1986. According to one of his staff members who has worked for decades with him, Shaida, before launching his own daily, had worked for different newspapers to hone his skills. He never compromised with journalistic ethics and believed in calling a spade a spade and for these reasons he had to suffer.

Even before he had launched Sahafi, a partnership product with a friend, Shaida worked as one of the secretaries of Kashmir’s only Sadr-e-Reyasat, Dr Karan Singh. He had also translated his autobiography, the Heir Apparent into Urdu with the title, Wali Ahaed. “When he was released after serving the detention under the PublicSafety Act for reproducing the sacrilegious write-up from the Deccan Herald, he went straightaway to a flat that Dr Singh had given him from within his estate,” one journalist who worked with Shiada till his arrest said. “Shaida was a hard-core anti-establishment editor. He suffered for that.”

“He had seen lots of ups and downs, but was always in high spirits,” one of the gloomy and teary-eyed staffers, who met in his deserted office, said. After the death of his wife ShamaZaidi who was from Hyderabad, he founded Shama Foundation in her name.

The main aim of the Foundation was to facilitate the marriage of poor girls, provide assistance to women suffering from cancer. “He will not turn the request of help from any pleader,” said one of his staff members.

Yusuf Jameel, who knew Shaida even before becoming a journalist, said the late editor was a thorough professional.

“He was sincere in his endeavours and clear about journalistic principles,” Jameel said. “In calling a spade and spade he had to face reprisals. In late December of 1986, when he criticized the article which had blasphemed revered Prophet Muhammad (PBUH), he was arrested and sent to jail.”

All through his life, the editor had to suffer financially for his uncompromising position on his principles. He never gave space to advertisements, which conflicted with his principles and because of which he had to endure many hardships. Later, when he bought a printing press for his newspaper, he had borrowed a loan from the financial corporation but continued to struggle to repay it.

“Lately I was in touch with him on phone and visited his residence often,” Jameel recalled adding that when he enquired about the loan, the late editor told him that he had to sell a piece of his ancestral land to repay it. Later as the financial conditions worsened, he had to sell even his printing press. “He had to face financial issues all his life,” Jameel said.

As the journalism and journalists continue to face relentless pressures at various levels from different quarters, late Shaida epitomizes the struggle. Even after three decades, Wadi Ki Awazhas limited reach. “He was also writing a book,” added Jameel.“He used to call me many times a day as I had told him to recall dates which due to the age had skipped his memory”.

Hours after burying him, the staff members were back to the office, to work silently in the seemingly gloomy and silent apartment of Waadi Ki Awaz (Voice of the valley) to bring out the following day’s edition.