In the demise of Rehman Rahi, Kashmir lost a doyen whose contributions to the Kashmiri language and literature are next to none, reports Yawar Hussain

In Rehman Rahi’s demise, Kashmir lost a legend. A quintessential poet and critic of the Kashmir language, Rahi was barely a few months away from celebrating his 98th birthday in May. He reportedly died in sleep. Kashmir’s only Jnanpith awardee, Rahi was laid to rest in a large open graveyard in the Vichar Nag, a satellite of the city’s Nowshehra locality.

Rahi’s contribution to the field of Kashmiri literature was unparalleled and he is credited for training and mentoring a generation of scholars, poets and writers. Even though the government was absent at his funeral, people across the globe condoled the death of the legendary poet who practically received every honour for his contributions to the Kashmiri language.

Abdul Rehman Mir

Born in Sher-e-Khas’s Wazapora area on May 6, 1925, in a financially weaker family, Rahi’s actual name was Abdul Rehman Mir. Rahi lost his father, Ghulam Muhammad Mir, a day labourer, at a young age and was then raised by his maternal uncle.

His enrolment in the historic Islamia High School of Rajouri Kadal saw him frequenting a bookseller for literary grooming. Apart from his daily brushes with some legends engaging in literary talks at the shop, the bookseller would order poet Iqbal’s complete work from Lahore for Rahi.

He joined Sri Pratap (SP) College for studying Persian and then the University of Kashmir for English. He completed a Master’s degree in both languages. It was during his college days that he started using the pen name Rehman Rahi for his writings.

Rahi taught Persian, Urdu and English before taking over as the first head of the Department of Kashmiri at the University of Kashmir from where he retired in 1985. The University of Kashmir’s anthem, Yee Mouj Kasheeri (Hey, Mother Kashmir), is authored by Rahi.

Earlier in the 1940s, Rahi joined the Public Works Department for a short stint at a cleric in the then Baramulla district. He soon left the service and donned the hat of journalism by joining the regional Urdu newspaper, Khidmat, as an opinion writer. The paper was an official mouthpiece of the Congress party.

His works in the paper were mainly focused on the partition and the misery it caused to the people of the region. His writings in the newspapers turned poetic when he expressed the grief and misery of the people.

While at Khidmat, he joined the Progressive Writer’s Association, which was affiliated with the Communist Party. Rahi also edited a few issues of Kwang Posh, the Progressive Writers Association’s literary journal. The Association was set up by him in 1947 and was wound up in the 1960s. From 1953 until 1955, he served on the editorial board of the Delhi-based Urdu daily Aajkal.

He like a generation of Kashmiris in that era was influenced by Communism which is also reflected in his poetic works of that era.

Later on in his life, he moved away from the ideals of communism which transformed his poetry as well. As militancy broke out in Kashmir, Rahi’s words expressed pain but never the politics around it. He has faced criticism as well as accolades for his neutrality on politics of the tumultuous Himalayan region, which now holds him in its lap. His famous song – Zindeh Rouzneh Baapat Loukh Cheh Maraan, Tche Teh Marakhna ((To live, people die: won’t you die; Will you drink this cup in silence, won’t you even cry?), was broadcast by the erstwhile Radio Kashmir Srinagar, during the early days of militancy. This song was hugely popular and it depicted the state of affairs on the ground.

Na tchu da’rie allan parde te na tchu brand’e dazaan tchong,

Waavas tchu dapaan kaw tche moloom karakh’e na

(Neither there are lights on nor do the window curtains move,

the crow is requesting the wind to see why it is so.)

Why Kashmiri?

Switching to the Kashmiri language was an outcome of a Mushaira in the Raithan (Budgam) in the 1950s where Rahi’s Urdu poetry wasn’t even understood by the literary doyens present in the function. On the other hand, all the Kashmiri poems received adoration and applause from the crowd.

From that day on, Kashmiri became synonymous with his poetry and writings. He described his association with the language in his 1966 poem Hymn to a Language:

“Oh Kashmiri language,

I swear by you,

you are my awareness and my sight.

You are a radiant ray of my consciousness”

“If there’s no Kashmiri language,” Rahi explained to one of his students in the documentary Rahi by MK Raina, “There will be no Kashmiri, and hence there will be no Kashmir.”

The Kashmiri language is a nation in itself, Rahi would always say. “The language works like a unifying force. The scattered Israelis were unified by the idea of their language – Hebrew. It’s all about being conscious of one’s identity.”

He championed the cause of taking out the Kashmiri language from the clutches of Persian and Urdu, which dominated the Valley’s literary scene. He believed that the Kashmiri language was essential for preserving the identity of the region mired in complexities and facing geographical challenges.

Rahi published more than a dozen books of poetry and prose in Kashmiri and is credited with restoring the language spoken by the maximum number of people of Jammu and Kashmir.

Some of his important works include poetic collections, Sana-Wani Saaz (1952), Sukhok Soda, Kalam-e-Rahi, Nawroz-i-Saba (1958), and prose including literary criticism Kahwat, Kashir Shara Sombran, Azich Kashir Shayiri, Kashir Naghmati Shayiri, Saba Moallaqat, and Farmove Zartushtadia

He translated the works of Baba Farid into the Kashmiri language while under the influence of Dina Nath Naadim, who along with Ghulam Mohammad Sadiq patronised the progressive writers.

Kashmir language wasn’t part of the syllabus until the erstwhile Prime Minister of Jammu and Kashmir, Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah introduced it from 1948 to 1953. But due to Abdullah’s bickering with Delhi, the language couldn’t come out of its confines. “Sheikh Abdullah did come out of the prison,” Rahi said, “but our language is still languishing.”

“He introduced intellectual richness, modern sensibility and accessibility to Kashmiri language and poetry,” Muhammad Amin Bhat, President of Adbi Markaz Kamraz said.

Besides, he also promoted Kashmiri in more concrete ways. He was one of the biggest supporters of a campaign to restore the language to schools, an effort that finally succeeded in 2000. He helped recruit teachers and scholars to teach Kashmiri and created a course to teach it to children.

Rahi has had a profound impact on Kashmiri culture and literature as a respected poet, forward-thinking critic and literary theorist. His distinctive use of Kashmiri to communicate universal topics was unique.

He stands out from his contemporaries because of his legacy as the creator of his own vernacular for expression. His creative achievements have significantly broadened the poetic and imaginative potential of the Kashmiri language.

Poet of Silence

The Poet of Silence is a biographical documentary film on the life and works of Rahi by filmmaker Bilal Jan. The film is jointly written by Jan and Shafi Shouq.

The 40-minute film talks about the inner poetic vision of Rahi during the turbulent years in Kashmir.

Jan says that Rahi is a different sort of poet from other poets of Kashmir. “Most of the Kashmiri poets have written about Tasawuf or Sufism or about Islam but Rehman Rahi is perhaps the only poet in Kashmir who writes about the human condition, the predicament of a human being and day-to-day problems of life,” he said. “Rahi is basically a realist poet; it may be because he is influenced by the Marxist thought.”

The filmmaker said that after engaging with Rahi’s poetry, he sometimes felt that only Rahi himself could understand the meaning of his verses. “His poetry is very meaningful and profound. Sometimes, I think no one, either a scholar or a common reader can truly discover any other meaning of his poetry, than the one Rahi himself articulates.”

Idealist Romantic

Dr Abid Ahmad, a literary critic believes that Rahi’s early poems depict him as an idealist romantic, aspiring for a perfect world where all his young passions would find fulfilment.

The poetic collection Nouroz-i Saba, he said bears the imprint of this mix of progressive ideology and romantic aspirations. However, unlike other poets who wrote under the influence of this movement, he was also aware of the importance of art as such.

“This compounding of the romantic with his passion for pure art is visible in many of his poems including Sheayir (The poet), Husn-e Lazawal (The immortal beauty) and above all in Funn Baraye Funn (Art for art’s sake). The last one celebrates art as an attitude, which in itself is sufficient to survive in life.”

As Rahi matured, Abid believes he shed off the borrowed idiom and instead started expressing his own sense of felt life. He says Rahi embarked on the pursuit of creating his own idiom commensurate with his individual experiences.

“Qa’ri darya Salsabeel, Sada, Aawlun, are some of the poems that were totally novel experiences in the Kashmiri aesthetic realm, setting it off on a path that was recognized for its classical and contemporary genius.”

Kashmir economist Haseeb Drabu believes Rahi was much more than a poet; as a literary critic, his contributions are as much as in poetry. “Kahwat (Touchstone, 1980), his book on literary criticism raised the profile of Kashmiri criticism by seeking to develop an indigenous critical idiom. These essays won him the Best Literary Critic Award of the State Cultural Academy,” Drabu wrote. “His other two books on literary criticism are Shaar Shinasee, 1982 and Kashir Shaeree Ta Waznuk Soorati Hal examines Kashmiri prosody within its own parameters that are distinct from Persian or Urdu and has caused quite a debate in literary circles,” Drabu adds.

Drabu says that a person doesn’t need to agree with Rahi’s politics to find beauty and meaning in his poetry.

“Political correctness is not a good literary standard. Everyone is fascinated by Ghalib’s poetry even though appalled by his colonialist political views! What is more relevant, the philosophical issues that underlie our society today –alienation, existential dilemma, social schizophrenia and human predicament, at personal, social and universal levels — are the principal themes of his poetry.”

Drabu adds: “Rahi sahib may have distanced himself from separatist politics right from the start, but that should neither enhances nor lessen his contribution to the construction of the Kashmiri identity.”

He says that a society which lacks iconic personalities needs to celebrate the ones they have like Rahi.

His poem Karav Kyah!—What To Do!— is a lament portraying the helplessness of the Kashmiri people. It is seen as Rahi’s attempt at breaking his silence.

“Many of Rahi’s critics questioned his silence during the traumatic times in Kashmir. But the fact remains, the poet’s pen always bled for the man on the street. Through his literary experiences, vision and translations, Rahi always spoke a commoner’s language in Kashmir,” says Anzar Mir, a scholar doing research on Kashmiri poetry’s post-colonial diction.

Research scholar Aarizoo Majeed draws parallels between Rahi and TS Eliot in her research. The two literary giants, she argues, have dealt with the concept of modernism and modern man in their respective poems: Soan Gaam (Our Village) and The Love Song of J Alfred Prufrock.

“The poets while working independently on the portrayal of the theme have excellently toyed with the senses of the readers whilst appealing to the sense of imagination,” says Aarizoo, whose paper was published in the International Journal of English Literature and Social Sciences (IJELS). “Like Eliot, Rahi talks about the disillusionment of man, his concerns, his social status, his feelings of being a nobody.”

Rahi is hailed for creating idioms of the modern Kashmiri language and working on the Encyclopaedia of Kashmir. Apart from his major translations, he is celebrated for guarding the Kashmiri language against Persian and Urdu influences.

He raised the human tragedies in Yemberzal (Daffodils), and O’Khodaya (O God!).

Author and columnist Maroof Shah says Rahi is best read as a cosmopolitan poet who adopted post-modern idiom to express what is most important in local tradition, at least at the poetic plane, and bears reading with the best contemporary poets across cultures.

“Poetry as such is an identity that subsumes other identities. By being artists other divisive identities are transcended without being derecognised. Rahi has appropriated in captivating and sublime language, the best of Persian Masters in (post)modern idiom.”

He says Rahi remains little explored by his contemporaries in Kashmir, even by the elite literary audience. “Very little quality criticism has been written on his works. His critical works have also suffered oblivion with time. He has remained, for the most part, obscure or inflected in an idiom that would fail to gain recognition for a variety of reasons. And he has not been immune to controversies and some serious critiques from his contemporaries.”

Though a general perception is that Rahi had maintained a distance from politics and situation, people who have read the poet disagree. They say that in almost every poetic collection, there are a few poems, which are contemporary in nature and are critical to the state of affairs. There are clear political poems written in the last decade.

Personal Life

Rahi married Zareena Mir (d 2019). He is survived by three sons, all doctors, Dildar Ahmad, Javed Iqbal and Farhad Hussain along with a daughter, Nighat Nowsheen; and five grandchildren.

Rahi received the Sahitya Akademi Award in 1961 for Nauroz-i-Saba (Advent of the Spring Breeze, 1958), a collection of his excellent poems, making him the youngest Indian to achieve this milestone.

Rahi was also conferred with the Sahitya Academy Fellowship in 2000. The fellowship was awarded in honour of his extensive contributions to Kashmiri literature and culture.

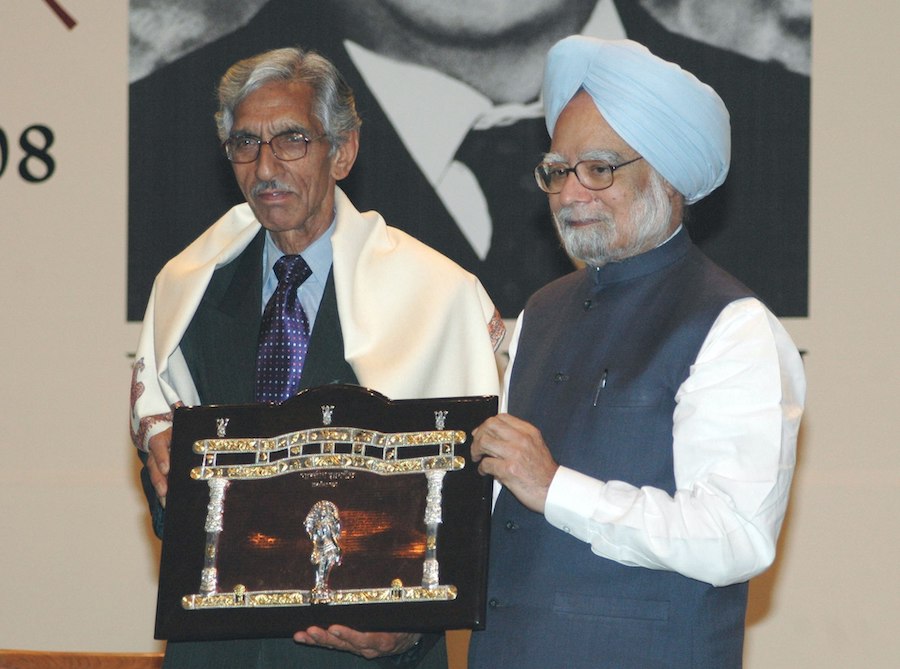

In 2007, Rahi was awarded the Jnanpith (for the year 2004) for his book Siyah Rood Jaren Manz (In Black Vernal Showers) released in 1996. The book is a commentary on political turmoil. The book, which is regarded as his finest work, also earned him a Padma Shri in 1999, the fourth-highest civilian award in India.

While receiving the Jnanpith Award, Rahi said: “It is the recognition of the language of our speech and thought. I am happy and sad today. Happy, because I was honoured. Sad, because my people continue to be in distress.”