The Flood of kids-carrying parents jamming roads and hospitals last week was just a historic instance of what a rumour can do to Kashmir in an IT-driven world. At a place where rumours are expected to be more correct than news, Masood Hussain looks into the evolution of rumour-mongering as a tool to enjoy, protest, panic, market and even shock the governance structure

(Photograph showing anguished parents with their children outside GB Pant hospital on 17 January)

By all accounts, the massive crowds in hospitals and traffic jams on roads on January 17, 2016, offered a grim sketch of what a rumour piggybacking the internet can do to Kashmir. Thousands of parents carrying their kids reported believing the polio drops administered to them in the forenoon were lethal. It was a disastrous response to a Facebook post by somebody, that police now says has been detained.

Despite mass media running a campaign against the rumour, it barely had an impact. By conservative estimates, parents cumulatively might have burnt fuel worth Rs 10 crore to reach the hospital with kids. Instances of doctors fleeing hospitals after watching the rush, people attacking the hospitals for finding the medical staff absent (it was Sunday) and doctors recalling their own kids from homes to re-administer polio drop to explain that vaccine was not lethal, were the sidelines of the mess.

“I was shocked to see some doctors also part of the crowd in an emergency with their kids,” Ahmad, a SKIMS official said. “They told me they know it is safe but still came fearing there might be something!” Ahmad says the doctor’s dilemma indicated a “trust deficit” in the system they are part of.

By all standards, this was the worst instance of rumour triggered chaos. But this was not unprecedented.

Srinagar did not sleep on January 19, 1990 night. All of a sudden, mosques switched on the mikes cautioning the public against using tapped water as reservoirs have been poisoned. It created such chaos that people came out on the roads and resorted to protests. Authorities switched off the power supply briefly but the mosque managers put on the battery back-ups to keep the people “informed”. Governor Jagmoha’s administration used the radio to negate the rumours but nobody listened as the mosque loudspeakers continued airing Jago Jago Subah Huie! (Awake! The Morning Has Dawned…) song.

By around 1 am, the army moves out and a curfew was imposed. There was resistance at various places and fires were shot in the air. People had drained every single drop of water they had. By morning, they were back to the routine!

In his My Frozen Turbulence in Kashmir, Jagmohan has written about how rumour-mongering was used as a tool to defy and frustrate his government. “…in the second week of April 1990 when food packets were being distributed by the army on behalf of the state government, during the curfew hours in Srinagar city, rumours were floated that these packets contained material, which when consumed, would cause frigidity amongst women and impotency among men, and that this was part of the overall conspiracy to reduce the population of the Muslims in the valley,” Jagmohan recorded. “The basic objective of the subversives in coining such rumours was to prevent the state administration from coming close to the people.”

The objective of the poisoned water rumour, according to Jagmohan was to goad the public to defy curfew restrictions en masse. “We countered such rumours by instructing the police and members of the paramilitary forces to eat from the food packets and drink from the municipal taps in the presence of the people in the streets,” claims the former governor whose reign, history had already recorded, in red.

The next massive crisis overtook Kashmir in the summer of 1993 when balaie (ghosts) started “attacking” people in the dead of their sleep. It started from north Kashmir and gradually entered Srinagar. During the course of reporting, I met real people who “miraculously escaped” from the “clutches” of these “ghosts”. These ghosts exhibited themselves in different forms in different localities. They were women in Mehjoor Nagar but men in Hyderpora. They were “without eyes” in Bemina and with iron claws in Nowgam.

The crisis dominated Kashmir for most of July and August, though some areas had reported the phenomenon in June and September as well. As one real murder in Sopore, attributed to a dagger attack by “ghosts” was reported, the crisis enforced insomnia.

Much later in 2000, I reported the same “ghosts” making life hell of the people around Brari Angan, the south Kashmir spot where five civilians were roasted alive. Some people had migrated to save their skin from “ghosts” invading their kothas.

These “ghosts” were akin to Naar-e-Tschour, people acting like thieves but actually setting homes afire, of 1977 forcing Kashmir to spend nights out to guard their properties. “The rumour was that Jan Sanghis are on the prowl and they are setting homes afire,” says Ghulam Nabi of Pampore. “This led people to stay organized, set up mohalla, village committees and would depute people on night guard.”

Over the centuries Kashmir has evolved rumour into a serious business. By jumping from Buddhism to Hinduism and later embracing Islam in the last three thousand years, Kashmir has retained a cultural cocktail. Being superstitious, exaggerating things (remember Alkulis Tulkul) and being in immortal love of rumour are key attributes of Kashmir.

“The Kashmiris,” Sir Walter Lawrence wrote in his The valley of Kashmir, “like the Athenians of old, are greedy for news, and every day some new rumour is started for their edification.” This has led to a set of maxims endemic to Kashmir.

Zainah Kadlah Pethah Thuk Gayih Ho! (The spittle has gone from Zaina Kadal.)

Missionary Rev J Hinton Knowles who spent a significant time of his life in Kashmir and did some fundamental work on Kashmir folklore compiled A Dictionary of Kashmiri Proverbs and Sayings in 1885.

“A man came from India to see Kashmir and enquire about the inhabitants,” Knowles writes while explaining this one-liner. “In the course of his ramblings he went to and stood on the fourth bridge and spat into the river; and then looked at the spot where his spittle had fallen, and said, “Where has it gone? Where has it gone?” The passers-by asked the meaning of this. He did not reply, but continued saying, “Where has it gone?” More people crowded around him until at last a vast assembly had gathered, and there was great danger lest the bridge should break. Then he told them that this spittle had gone, and the crowd scattered, and the man from India went back to his own countryman and told them what stupid people those Kashmiris were.”

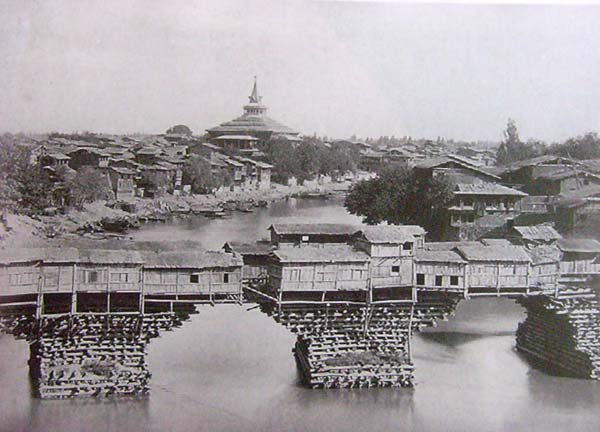

Zaina Kadal, central to the city, is fourth of the seven bridges. A principal thoroughfare, Knowles saw it the principal means of inter-communication between the two sides of the city. “It is said that whatever news there may be, it will certainly be known some time or other during the day on Zaina Kadal,” he recorded.

To illustrate the significance of Zaina Kadal, this missionary revisited the misrule of Afghan tyrant Azad Khan (1763 AD). As one of his wives was about to give birth to a child, Khan promised her presents if she gave him a boy. “But if it should be a girl, I will slay both you and the child,” he is reported to have told her. The girl was born and he killed her and threw the infant in the fireplace.

“Uneasy as to what report might have spread concerning this dastard act, he sent his servant to Zaina Kadal to see whether the people had got wind of it, and if possible the report was to be traced and the originators seized,” Knowles recorded, more than a century later. “The servant went and in a little while, four or five persons were seized and the report tracked back to one man.”

During the interrogation, the man replied, “I saw in a dream Shah Hamdan or one like unto him, coming to me and saying that such was the case in the king’s house. Accordingly, I told the people, whom I met, of my strange vision, and on Zaina Kadal there was quite a little company of strangers to whom I related my strange experience.”

“True”, Knowles recorded the king saying. He went to the bridge and destroyed all the houses that King Zainulabiddin has erected on either side of it. “Even now authorities are afraid of the bridge and the police have special orders to prevent any gathering there.”

“The Zaina Kadal or the fourth bridge of the city, used to be the place where false rumours were hatched, but now the newsmakers have moved to the first bridge, the Amira Kadal,” Lawrence wrote while taking the talk further. “Though the wise knew that Khabr-i-Zaina Kadal was false, the majority are not wise, and much misery is caused to the villagers by the reports which emanate from the city.” He terms Kashmiris as “unstable” and Hawabin, the wind watchers.

“…the weakness for the rumours was made use of by the followers of Sheikh Abdullah in weaving a halo around him and propping up a personality cult,” Jagmohan wrote in the 1990s after he was recalled. “During the thirties, for example, rumours were deftly spread that some leaves of Chinar trees had Sheikh Abduallh’s name imprinted on them.”

Historically, rumours were used as weapons, both by people and the state. As Partap Singh succeeded his father Ranbir Singh, his younger brother Amar Singh was eyeing the Kashmir throne. To destabilize him, Amar Singh was adversely briefing the British and almost got him deposed. People knew the mess in which the rabid anti-Muslim monarch was. They would trigger rumours and these would travel on horses so fast that even the ‘king’ would be afraid of. The king had to hire members of the House of Lords to seek some relief.

“I wish to ask my noble friend the Secretary of State for India whether there is any foundation for the rumour, which seems to have occasioned some alarm in different parts of India, that it is the intention of the Government to take possession of the Native State of Kashmir,” Lord Herschell, once asked in a debate on king’s behalf. “One of the rumours very current in India is that, when the Viceroy comes to Lahore, the Foreign Office will invite the Maharaja to meet his Excellency there. The Maharaja would, of course, come, and then he would be persuaded to pen a real edict of resignation. We notice this rumour at all to show how people are prone to attribute all sorts of motives to the Government.” Partap Singh eventually wrote to the Viceroy in April 1889 saying it was his real brother who was “circulating the worst rumours against me”.

In a suppressed situation where formal news was hagiography, rumours were the ‘news in making’. People knew the fall of Uri on October 26, 1947, but the regime of Hari Singh remained busy in palace routine. In the evening it fled when Mohara powerhouse was destroyed snapping the power supply to his Palace.

To retain the interest of the people against Hari Singh’s rule, Sheikh Abdulla’s spin doctors resorted to rumour-mongering. “A jailer asked him to jump into a cauldron full of steaming mustard oil,” an IANS report on Kashmir rumours mentioned. “Abdullah put his finger in it to test the temperature and it cooled down – goes the story.”

In the late 1960s, the daily intelligence diary submitted to top bosses contained an essential detail – a separate column reserved for the day’s rumours. “Believe it or not, all the rumours had such instant acceptability that markets would be closed or opened on the strength of such rumours,” the IANS reported quoted a retired police officer saying. “A strange truth about rumours in the valley is that they gain immediate credibility once denied by the government.”

Mongers resorted to rumours in every regime to hit a target and it invariably had a purpose. In April 2008, the custodians at the Mukhdoom Sahab shrine in the old city witnessed an unseasonal rush of devotees and parents of single male sibling were flocking the shrine with a few kilograms of rice. The massive rush that led to shrine managements created additional storage capacity in response to a claim that Sopore faith healer Ahad Bab had dreamt of a threat to boys who have no brothers. Nobody checked the veracity of the dream especially when the cop-turned-mystic had never been seen talking and has rarely been seen in clothes.

Seemingly, somebody was checking if “traditional Islam” has been neutralized or not.

In Kashmir, it has been said that news can be incorrect but not the rumour. On January 5, 2016, a senior minister from Delhi indicated to his functionaries in Jammu that the Chief Minister is seriously unwell. It travelled so quickly that 24 hours later Naeem Akhter was fighting rumours. “He (Mufti) is in the same condition as he was yesterday,” Akhter said. “He has responded to treatment. Some fake accounts on social media are spreading rumours.” Barely 14 hours later, Mufti breathed his last.

The ghost operations in 1993 stopped within days after a Delhi newspaper wrote that the security forces should stop the non-sense of ghosts for night domination. More than twenty years after the poisoned-water rumour, a middle rung revenue officer, working in the office of Divisional Commissioner, told me that after the night-long sloganeering and curfew a top army officer visited the complex and left a meeting in anger. “We were told later that the governor’s administration had hired lot many civilian trucks and were supposed to make random arrests that night,” the officer who is still alive told me. “It failed.”