Kashmir produces seven million kg of wool a year but lacks the capacity to process even one per cent of it. Sold at throwaway prices, the finished products cost us billions. It is not the money alone. Kashmir is losing thousands of jobs because of the ‘black sheep’ in the policy-making who never prioritised the sector, Shams Irfan reports.

Jammu and Kashmir produce around seven million kg of wool annually but without the infrastructure in place, more than 90 per cent of it ends up in factories outside the state. Till the late 1980’s, the wool-rich state had major stakes in the manufacturing of wool products as everything from the grading of wool to the manufacturing of end products was done locally. As the political situation changed in Kashmir and violent protests against Indian rule became a norm, the noise of the machines instantly fell silent. And in a bid to silence the dissenting voice of the masses, these industrial complexes were turned into garrisons overnight.

The political uncertainty in Kashmir valley created an opportunity for traders from Amritsar, Ludhiana, Panipat and other parts of India who started exploiting the market by buying unprocessed wool from cash-starved traders in Kashmir. Even the Jammu and Kashmir Sheep and Sheep Products Development Board (JKSSPDB), which was established in 1979 and tasked to stabilize the wool prices by offering breeders minimum support price, failed to contain the growing appetite of outsiders for Kashmir wool.

The idea behind the creation of JKSSPDB or Wool Board was to eliminate middlemen and create direct contact with breeders through its 20 procurement centres spread across J&K. But with limited funds available to buy wool and a lack of local market, the Wool Board failed to end woes of the breeders. Out of seven million kg of wool produced this year in Kashmir, the Wool Board has so far booked only 1.6 lakh kilograms of wool.

“Till September end, the Wool Board procured one lakh kg of wool while another one lakh is expected to reach the Nowshera warehouse in October after local breeders start sheering,” said Dr Tufail Ahmad Qadri, General Manager, Wool Board.

Once a known address in Nowshera, it takes a while to locate the office of the Wool Board which operates from a small dilapidated building which can be accessed through a small iron gate squeezed between two heavily guarded bunkers. Once inside the complex, one could see big industrial warehouses guarded by concertina wires as they were converted into makeshift accommodations for security forces during the early 1990s when conflict erupted in Kashmir valley.

Dr Qadri feels the board could benefit more breeders if it had enough funds and proper space for the storage of procured wool. But presently, the Wool Board only concentrates on stabilizing market prices for benefit of the breeder as it is impossible to buy all the wool that is produced in Kashmir.

In a small warehouse adjacent to the Wool Board office, the raw stock collected from breeders through procurement centres is sorted. “After procuring wool, the first process is to grade it according to its colour, length and fineness of the wool,” said Dr Qadri.

At Wool Board, the grading is done manually by local girls who are offered a minimum support amount of Rs 1.25 per kg. After grading is done, the wool is sent for scouring (cleaning) to the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) next door.

“UNDP has limited capacity,” said Dr Qadri. The UNDP started as a five-year pilot project in Kashmir in 1978 to facilitate breeders to get their samples tested at the centre. The project, funded by the central government with land and employees under the control of state government, was transferred to the state government once the duration of the programme was over. UNO helped in procuring machinery from England, Japan and Italy. UNDP had foreign consultants who would train locals in different processes of yarn making. “But everything changed after 1989,” said Manzoor Ahmad, a senior employee at UNDP.

For one decade, UNDP remained defunct and resumed only after the present deputy director took over in 2007. But over the years, the role of UNDP has remained limited to sampling purposes only. Weavers can see how their wool would look after spinning by getting a small sample spun at UNDP. “It is just a facilitation centre and not a commercial unit,” said Tahir Ahmad Shawl, deputy director, of UNDP. At UNDP, about 300 kg wool can be scoured per day per shift while only 150 kg of loose wool can be dyed in a day. It can make only 300 metres of finished fabric in a day if run to its full capacity.

Last year, the Wool Board failed to attract breeders to sell their wool as the minimum support price was much less than the prevailing market price. “We immediately revised our prices from Rs 50 to Rs 55 per kilogram as we failed to attract breeders,” said Dr Qadri. Despite last-minute revisions of prices wool, the board could procure only 50, 000 kg only. This year too, the Wool Board has revised prices within a week’s time and is now buying wool at Rs 80 per kg instead of Rs 75 earlier.

On the other hand, Handloom Development Corporation (HDC), a semi-government organization is one of the largest consumers of wool in Kashmir. The corporation procures wool from many sources like Wool Board, SKAUST and directly from local breeders. Last year HDC consumed only 25,000 kg of raw wool which was procured partly from the Wool Board and through breeders directly. But this year the corporation has booked around 60 thousand kg of wool already.

The raw wool is then sent to UNDP where it is sorted, carded and scoured. “Last year UNDP charged us Rs 25 per kg for scouring,” said Irshad Ahmad Wani, Assistant Financial Advisor, HDC. “Around 40 per cent per kg is lost as wastage during scouring,” said Wani.

As there is no facility available to spin a large quantity of wool in Kashmir, HDC sends the scoured wool to mills in Jammu, Amritsar, Panipat etc. for dyeing and spinning. “Depending on the colour pattern, dying costs around Rs 65 per kg at Jammu while spinning adds another Rs 35 to the cost. These costs exclude transportation charges,” said Wani.

Once spinning is done and wool is transformed into yarn, it is transported back to Kashmir from where HDC sends these yarns to different decentralized centres situated in Kralpora, Bandipora, and parts of Pulwama. One kg of raw wool produces around 500 grams of finished yarn. Weavers in these decentralized centres are employed by HDC against a set amount. “Last year, HDC paid Rs 88 lakh as wages to the weavers,” said Wani.

Interestingly, HDC invests around Rs 200 (including transportation and other charges) extra for a kilogram of wool to be turned into yarn from outside the state.

Handloom Development Department (HDD), which is a part of Wool Board, has 10 clusters in Jammu and Kashmir. Every cluster has more than 300 weavers under its fold. The main aim of these clusters is to provide basic training to weavers in designing, colours, patterns etc so that they can keep experimenting in producing improved products.

In 2010, these weavers made tweed which was sold to a Delhi-based trader for Rs 350 per metre. The same trader sold the finished products somewhere between Rs 4500 to 5000. “If we have the spinning facility here, we could easily come up with different varieties of tweed to compete in the market,” said UNDP deputy director Shawl.

This year, the cost of unprocessed wool has gone up to Rs 80 per kg from Rs 55 in 2011. HDC bought raw merino wool for Rs 102 per kg which will be sent outside the state after sorting and grading locally for carding, scouring, dyeing and spinning as these facilities are not available locally.

“After spinning the wool we buy it back in the form of yarn for around Rs 300 per kg. If spinning facilities would have been available locally, HDC would have been able to save around Rs 180 on every kg of yarn,” Shawl said.

Apart from merino wool, another variety known as BBCC which is used for tweeds is available in the local market for Rs 57 per kg but as spinning is done outside, the fabric is sold after spinning for as high as Rs 335 per kg. Merino quality wool is used for blankets and shawls as its fibre length is longer than BBCC wool. “The cost of end products will come down automatically if everything is done locally once again,” feels Shawl.

Experts feel the state government must invest in creating infrastructure for spinning wool which could save a large amount of money which is being paid for spinning of wool outside the state and open up opportunities for unemployed youth.

Till a few years ago, HDC would get a share of its wool spun at Government Wool Mills Bemina (GWMB). A Jammu and Kashmir Industries undertaking, GWMB was established in 1970 with the purpose to provide end-to-end facilities like scouring to manufacture of finished products like tweeds, shawls and blankets in one place. But with its obsolete Belgium spinning cords, the GWMB is not able to meet the growing market demand.

A revival plan for HDC was started last year by the government. “It is a five-year plan which will help the corporation to become economically viable,” said Wani. HDC cut staff since 2009-10 and as many as 161 employees were relieved under voluntary retirement schemes and golden handshake.

Since its establishment, GWMB has failed to make its mark in the local market and has ever since proved to be a loss-making unit for the government. According to sources, in the last financial year, GWMB distributed salaries and overheads to the tune of Rs 3 crore while the income from the sale of finished products during the same period was Rs 54 lakhs only.

“It is a loss-making entity which either needs to be upgraded properly or shut down completely,” said an industry insider on condition of anonymity. GWMB which has two carding units (one each for normal and fine quality wool) and two spinning units has an annual capacity to consume only 1.5 lakh kg of wool. If worked to its full capacity, GWMB can produce around 4 lakh meters of tweed fabric annually.

Being the only end-to-end wool-based mill in Kashmir, GWMB produces finished products under three different categories. Tweeds and blankets are made from local wool. Second is worsted suiting Serge and Angola which is made from Merino wool tops imported from Australia and the third is PV yarn (polyester plus viscose) which is also made from imported wool.

“GWMB consumes only a small amount of total wool produced in Kashmir annually,” said Fazal Qadir, sales supervisor at GWMB.

Bemina Mills sold finished products worth Rs 54 lakh only from its 11 showrooms (10 in Kashmir and 1 in Jammu) which includes an order for uniforms from government departments like SKIMS, state forest protection force, Srinagar Municipal Corporation, JK cement, etc.

As the demand for tweed coats and woollen blankets are going down because of fierce competitive pricing from Amritsar and Ludhiana-based players, GWMB’s main source of income in the last few years has been government orders only. But GWMB receives only a small fraction of orders of various government departments. For example, Jammu and Kashmir police places order worth Rs 10 crore annually which include uniforms and 50,000 blankets. “If we get such big orders, GWMB can never run in losses,” said Qadir.

Unfortunately, police and other government buyers like state hospitals, fire services, etc. stopped placing orders with GWMB over the last five years. This year too, orders worth crores of rupees are already placed outside the state in Amritsar, Ludhiana, Jalandhar, etc. while stocks worth Rs 1.5 crore lie neglected in GWMB warehouses. “These departments prefer low-quality Amritsar-made products to original Kashmiri wool. It is cheap and also earns them huge money in kickbacks,” said a GWMB official on condition of anonymity.

Around 3000 pure wool blankets lie wasted at the Wool Board warehouse for want of clients since 2009. “If government departments start buying Kashmir wool products rather than placing big orders with outsiders it could help the handloom industry in a big way,” said Dr Qadri. “Punjab woollen industry actually flourished on Kashmir wool,” said an insider at HDC.

In September 2012, GWMB has sold finished products worth Rs 30 lakhs only while an order worth another Rs 40 lakh from Srinagar Municipal Corporation is expected to be supplied within the next few days. But these small orders cannot help GWMB become financially independent. GWMB imports 30, 000 to 40,000 kg of wool from Australia annually while it buys only 10,000 kg of Kashmir Merino quality wool from Wool Board.

But Qadir feels that things have started to show positive signs of growth as production has considerably gone up over the last few years. GWMB produced 16,000 meters of finished fabric in 2010-11, while in 2011-12 it was 42,000 meters and this year it is expected to cross 1 lack meters.

At the same time, Qadri strongly feels that the state government must make it mandatory for all its departments to place orders with HDC, HDD or GWMB only. “By adding just two more carding units to GWMB, the entire produce of local wool can be spun locally,” said Qadir. HDC which produces 4.7 lakh metre yarn annually has set a target of around 1,900 Pashmina shawls and 3000 coats this year.

Recently, the government started renovating the spinning cards at GWMB by replacing foreign machinery with Indian-made spinning cards. But industry experts feel that it is nothing more than patchwork which is not going to help the dwindling industry. “Efficiency of Indian spinning cord is not good as compared to Swiss and Belgium-made cords. Their life is good and maintenance is much lower,” an industry expert said.

According to sources, it was observed during a high-level meeting attended by the economic advisor to the state government that any renovation of Bemina’s obsolete and worn-out machinery is simply a waste of money. On the other hand, under the prime minister’s special economic package to Jammu and Kashmir, a proposal for upgrading existing facilities lying shut at Shoddy Spinning Plant (SSP) at Solina in the summer capital Srinagar was put forward. SSP, a unit of Jammu and Kashmir Industries (JKI) which was closed by virtue of cabinet order, was treated as a special case and proposed to be transferred to HDC for manufacturing and construction of yarns to be used in the handloom sector. Though spinning is not part of the handloom sector, SSP was taken as a special case. The transfer was sanctioned in 2010 but there has been no progress so far. With imported machinery still in good condition, SSP was originally a recycling unit and it has four carding units installed.

The biggest private spinning unit, Matto Worsted Spinning and Weaving Mills in Srinagar’s Nowshera area, which was established in 1963, had the capacity to produce 250 kg of yarn per day. Because of conflict, the mill was closed in 1990. “We had 100 strong skilled labourers who were mainly from outside the state. But once violence erupted in Kashmir, they left en masse,” said Abdul Majid Matto, owner of the mill. “It was a profit-making unit,” said Matto.

Till the late ’80s, the handloom sector was organized. Procuring of wool was done by Wool Board. The wool was then sent to UNDP for scouring and dyeing. Yarns were made at Bemina Mills. Then yarns were turned into the fabric at HDC. The fabric was once again sent to UNDP where finishing was done. Finally, the HDC would market the end product.

But the exorbitant annual establishment and overhead expenditure including annual salary and wages cost HDC Rs 640 lakh annually. In 1981, Government Handloom Silk Weaving Factory at Rambagh, a loss-making unit which was earlier under JKI, was transferred to HDC. Right from its transfer, the unit is non-functional but the workers are being paid wages regularly.

Rich History

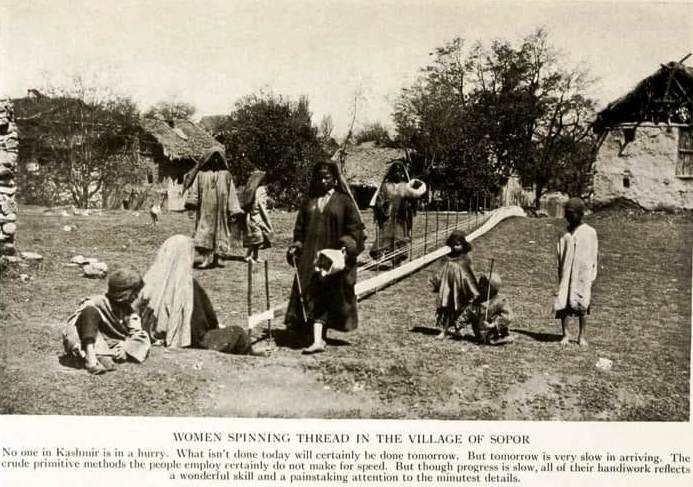

Before Second World War, Kashmir had direct trade links with Europe and America. Handloom was a flourishing industry. From sorting unprocessed wool to finished products, everything was done locally. In the Pulwama district, weavers were famous for their skills as spinning was done with the hand. In 1975, the handloom industry was revived under the 20-point programme of Prime Minister Indira Gandhi.

Modernized fly shuttle looms were introduced and given to weavers at subsidised rates. It cost around Rs 1600, of which 75 per cent was subsidised by the central government and the rest was recovered from weavers in easy instalments deducted from their monthly earnings. The transition from hand-operated looms to more sophisticated fly shuttle looms helped in the socio-economic development of the villagers in Kashmir.

Traditionally, the weavers in Kashmir are agriculturists who work on looms for extra income. “They earned good money after fly shuttle looms were introduced. A weaver used to earn around Rs 800 per month during the ’70s which helped in lifting their socio-economic conditions to a great extent,” said an industry expert.

These weavers were entirely dependent on wool produced in Kashmir as it was considered best for the production of shawls and tweeds. Because of the lack of coordination between breeders and weavers, breeders were forced to depend on middlemen to sell their produce. Up to the early ’70s, unwary breeders used to sell their produce through a barter system. Local moneylenders and middlemen often used to buy wool from breeders living in far-flung areas against pretty household items like tea, sugar, tobacco, etc. It was only after the Wool Board was formed that the handloom sector got organized.

In order to increase the volume of merino wool production in Kashmir, the government introduced a crossbreed variety of sheep during the late 70’s. But it backfired as the merino wool produced by cross-breed sheep was affected badly by the local unfavourable climatic conditions. The final product of this new merino wool developed crimps even after going through multi-level processing.

In a state like Jammu and Kashmir where the employment rate is one of the lowest in the country, the revival of the handloom sector and setting up the infrastructure to treat the raw material locally can generate huge employment opportunities. The policymakers need to take bold decisions to stop this sector from meeting a quiet death.

Revival Plan

In a November 2011, meeting of the Monitoring Committee on Economic Development (recommendations of the Rangarajan Committee), the Development Commissioner for Handloom, Government of India, has approved the implementation of the second phase of the Integrated Wool and Wool Design Centre (the project) under the Prime Minister’s package for J&K, at a cost of Rs 10.36 crore.

The project foresees the provision of additional machinery and equipment in various sections of UNDP and Shoddy Plant.

Prof. Behera of IIT New Delhi, who was earlier engaged by the Development Commissioner for Handloom, GoI, during his discussions with the Economic Advisor is reported to suggest that restarting of Shoddy Plant will help in meeting the requirements of handloom weaving in the state.

The experts also opined the existing government orders requiring various government departments to procure all their requirements of woollen blankets, Serge/Worsted cloth, and other woollen and cotton fabrics only from JKI and HDC without inviting tenders from outside the state should be reiterated and strictly enforced.

Hello, black sheep of UNDP have done nothing fro Kashmir.

India’s Rural Development Minister Jairam Ramesh talked about this report in his speech in Sopore last month. He said J&K can do a lot if it processes what it already has and stop selling the raw material at throwaway costs. Good story. Keep it up.