by Muhammad Nadeem

“We have, without doubt, sent down the Message; and We will assuredly guard it (from corruption).” – Al-Hijr -15:9

Scattered across the globe, from the arid plains of Yemen to the cultured halls of Dublin, lie pages worn by time yet immortalised by the words they bear. Fragile vellum and brittle papyrus harbour secrets sparse in letters but rich in meaning, reflecting flickers of divine revelation kindled centuries ago. Those who seek out these ancient fragments tread carefully, for they follow the footsteps of Prophecy itself.

In the dry desert air of Sanaa, Yemen rests a cache of parchment leaves too delicate to touch, yet too precious to ignore. Penned in looping Hijazi script, these tattered tiles once lined the walls of the Great Mosque, murmuring verses of the Holy Qur’an to hushed congregations below. Dated to the mid-first century of the Hijrah, they rank among the most venerable Qur’anic manuscripts known. Scholars marvel that their slender forms survived the winds of change that eroded their mortar home. What stories might they share, if words could speak?

Far across the Mediterranean, the hallowed halls of the Egyptian National Library echo with scholarly footfalls. Within those towering archives lie regal manuscripts said to have been penned by Caliph Uthman himself. Their sturdy kufic letterforms exude authority, the gilded illuminations reflecting the wealth of patronage bestowed upon the Book. Yet it is the words themselves that command awe, linked by tradition to the generation that received them.

Northwards, past marble pillars and gilded shelves, the Chester Beatty Library in misty Ireland shelters folios far from their Arabian origins. Penned on parchment likely grazed by Nile goats, their faded Arabic betrays an African genesis. Yet through radiant illumination, Ireland has adopted these orphans from the House of Revelation.

So, it goes, across oceans and borders meaningless to words from a realm beyond. Istanbul, Paris, Mashhad, St Petersburg — in libraries grand and modest, cursory and complete, lie testaments to a Scripture born perfect amidst imperfection. To those who seek them, these manuscripts bequeath glimpses into the earliest flowering of a book unbound by time or place. In fragile beauty persists living memory, awaiting the curious, rewarding the reverent. Wherever they may wander, such relics remind us: there are verses even stone and bricks may keep, never to be erased from mortal hearts.

The Sanaa 1 Palimpsest

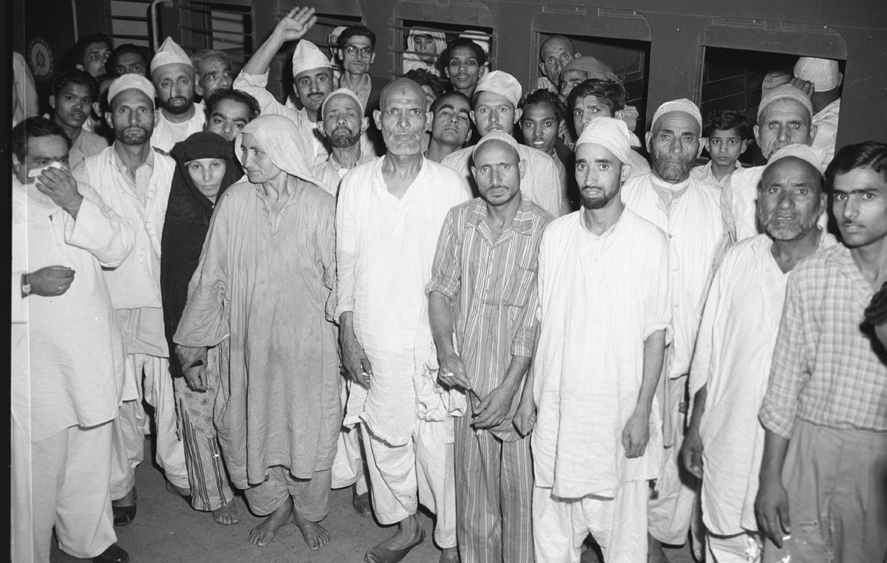

In 1972, construction work at the Great Mosque of Sanaa in Yemen uncovered a stash of old manuscripts concealed in the mosque’s ceilings and walls. The cache contained around 12000 parchment fragments dating back to the first centuries of Islam. Most were Qur’anic manuscripts written in early Hijazi and Kufic scripts. This marked one of the biggest discoveries of early Islamic texts.

Initially, some folios were likely taken from the mosque before the collection could be properly secured. In 1981, a preservation project funded by Germany began, with Yemeni and German scholars restoring and analysing the fragments that remained in Sanaa. The collections are housed at the House of Manuscripts in Sanaa.

Among the fragments found was a parchment palimpsest later labelled Sanaa 1, containing two layers of Qur’anic text. The upper layer is from the standard Uthmanic tradition, likely the seventh or eighteh century CE. Remarkably, the lower layer is from a non-Uthmanic textual tradition diverging from the canonical text. This makes Sanaa 1 hugely significant as the only known non-Uthmanic Qur’an.

Through radiocarbon dating the lower text has been dated to before 671 CE with 95 per cent accuracy. This early dating makes it one of the oldest Qur’an manuscripts discovered. The lower text contains many variations from the Uthmanic text, suggesting the two traditions had already diverged before the standardization of Uthman’s text in the mid-seventh century.

Initial studies have analysed some folios now in auction houses and confirmed the lower text’s non-Uthmanic nature. Scholars like Puin and Sadeghi have proposed connections to Companion codices and manuscripts prepared by caliphs like Ali. The variants suggest a significant role for orality in the Qur’an’s early transmission.

In essence, Sanaa 1 represents a uniquely early non-Uthmanic Qur’an whose variants can elucidate the development of the Qur’anic text in the decades before Uthman’s standardisation. Comprehensive scholarly access and publication of this manuscript have immense potential to significantly progress understanding of the Qur’an’s origins and compilation. It may provide concrete historical evidence illuminating the canonisation process, bridging current knowledge gaps in crucial ways. But such study remains limited presently.

The Sanaa palimpsest is arguably the most important Qur’anic find of recent times. Early radiocarbon dating and analysis of initial folios point to its critical value. But achieving its full potential requires overcoming access barriers and conducting an exhaustive scholarly study of this priceless artefact.

The Samarkand Kufic Quran

The Samarkand Kufic Qur’an is one of the most celebrated early Qur’an manuscripts, long attributed to Caliph Uthman ibn Affan. Today only about a third of this monumental volume survives, housed at the Hast-Imam Library in Tashkent, Uzbekistan.

The earliest references emerge in the nineteenth century after the Russian occupation of Central Asia. Local legends stated the manuscript was gifted to Samarkand by Ottoman Sultan Bayezid I. Others claimed it was seized by Timur in his conquests. Intrigued by the tales, General Abramov acquired the Qur’an for the Imperial Library in Saint Petersburg in 1869. There it was studied extensively, with scholars like Shebunin providing detailed descriptions in 1891. A questionable facsimile edition was made in 1905. In 1917, Russia returned the Qur’an to Uzbekistan, where it was kept in Tashkent. A new facsimile was made in 2004.

Around 40 leaves from the original have since been identified in collections worldwide, likely removed before it was sent to Russia. Reports state 50 pages were taken in the early nineteenth century. Over a dozen were stolen after the Qur’an’s return to Uzbekistan.The original is estimated to have contained over 950 parchment leaves. The large existing pages measure 680 x 530 mm, requiring special bifolio binding. Two Kufic scripts are found across twelve lines per page. Modest illuminations feature geometric designs without gold.

The text mainly follows Kufan conventions with some early idiosyncratic spellings. Notably, it has individual dotted consonants per Mashriqi norms, even rare double-dotted qafs. This distinguishes it from other early Qur’ans. Its origins remain uncertain. Local legends of Uthmanic origins are unverified. Radiocarbon dating proposes a seventh to nonth century date. Some experts suggest it was commissioned by Abbasid Caliph al-Mahdi instead. The lavish Samarkand Qur’an has long fascinated scholars despite its fragmented state today. A thorough study of dispersed leaves may someday unveil its mysteries. But the manuscript will likely retain its aura of intrigue as one of the most celebrated treasures of Islamic civilization.

The Blue Quran

The Blue Qur’an is one of the most magnificent Qur’anic manuscripts ever produced. Its pages are dyed a rich, dark blue and the text is written in flowing gold Kufic script outlined in black. Each Surah title is marked by a decorative band containing intricate geometrical patterns and jewel-like accents of blue and red, ending in a curling finial in the margin.

The manuscript was long shrouded in mystery. Its earliest documented history begins in the early twentieth century when several leaves appeared in private collections and on the art market in Istanbul. In 1912, Frederik Martin suggested the Blue Qur’an had been commissioned by the Abbasid caliph al-Ma’mun for the tomb of his father Harun al-Rashid in Mashhad, Iran. However, following the discovery of more folios in Tunisia, it became clear the manuscript was associated with the Great Mosque of Kairouan.

Further research by scholars like Jonathan Bloom and Alain George has led to a radical reassessment of its origins. Based on the style of script, which represents a transitional stage between early Kufic styles, as well as the sparse notation and lack of vocalisation, the Blue Qur’an can now be confidently dated to the late eighth or early ninth century AD – the early Abbasid period. Its royal colour scheme and monumental format suggest it was an imperial commission, possibly from Baghdad.

Today, around 100 leaves from the Blue Qur’an are known, dispersed across museums and private collections worldwide. In its original state, the manuscript is estimated to have contained some 600 giant pages. Each leaf was meticulously prepared – the parchment dyed blue, burnished and ruled. The calligraphy was executed in gold powder ink and outlined in brown. Decorations were added before the leaves were finally assembled and bound.

The effect of this precious manuscript when opened would have been mesmerising. The gold script shimmering on deep blue evokes a sense of divine light emanating through the darkness. This symbolism was meaningful in its original context, where the Qur’an is perceived as a sacred source of divine radiance sent down to humanity. The Blue Qur’an thus represents the genius of early Islamic book arts, wedding beauty and faith in a masterpiece of rare splendour.

The Codex Parisino-Petropolitanus

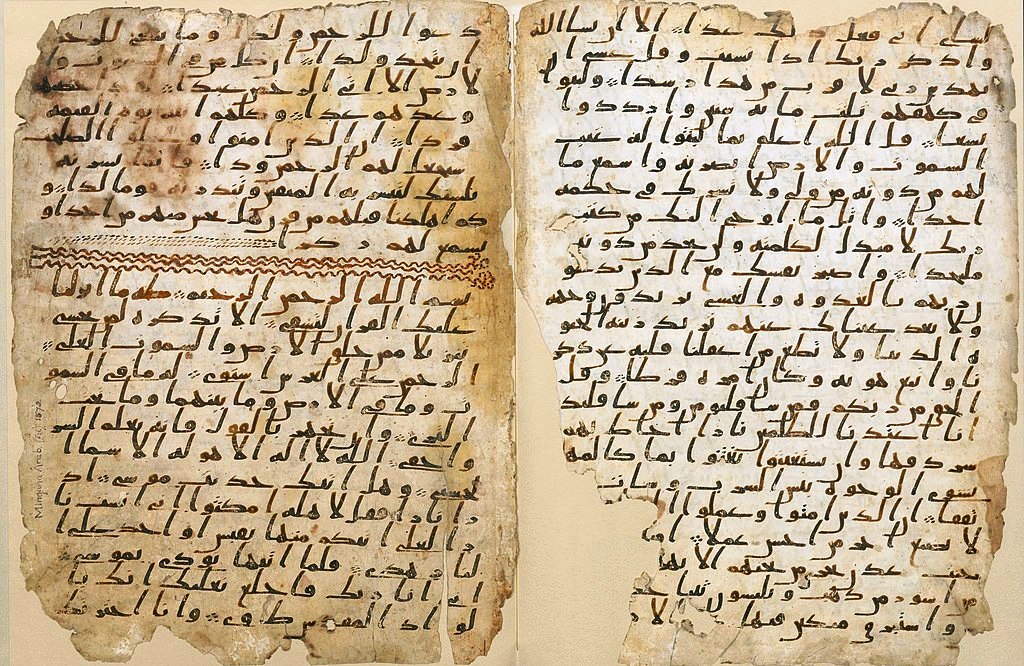

The Codex Parisino-Petropolitanus is an early fragmentary Qur’an manuscript dated to the late seventh or early eighth century CE. It originally contained over 300 folios written in Hijazi script, but only 98 survive today. These are divided between collections in Paris, St. Petersburg, the Vatican, and London.

The manuscript was discovered in the nineteenth century by French scholars Marcel and Asselin de Cherville in the mosque of Amr ibn al-As in Fustat, Egypt. The folios measure around 33 x 24 cm and are written on parchment in a space-saving long-line layout without margins.

At least five different copyists worked on the codex, identified as Hands A-E Hand A penned the majority of the surviving folios. The copyists used an early form of Hijazi script with sporadic, inconsistent use of diacritical dots. Each employed its own system of elongated dots to mark verse endings.

Based on palaeographic analysis, the manuscript is dated to the late seventh century CE, in the early Umayyad period. The place of copying is uncertain, but a Syrian origin has been suggested given the text’s canonical variants.

The text contains both standard ‘Uthmanic readings sent to Damascus as well as non-canonical variants and verse divisions not matching the standard Qur’an. This indicates it may reflect a stage of transmission before the Qur’an’s complete canonisation.

Later corrective hands revised the text up until the ninth to tenth centuries CE, showing it remained in use for an extended period. These corrections erased some rare readings, modifying the text toward the standard version.

Codex Parisino-Petropolitanus provides invaluable insights into the early evolution of the written Qur’anic text. As one of the oldest surviving Qur’an manuscripts, its textual features illuminate the initial transmission process in the decades following the establishment of the Uthmanic archetype.

Careful study of its orthography, scribal practices and textual variants allows deeper analysis of the Qur’an’s standardisation and canonisation in light of non-Uthmanic traditions that still circulated in the late seventh century. The manuscript demonstrates how the authoritative text was still undergoing refinement and gradual solidification even while Uthmanic prototypes were spreading.

Codex Parisino-Petropolitanus represents a crucial historical snapshot of the Qur’an’s textual development shortly after the promulgation of the Uthmanic mushaf, capturing a transitional stage before the definitive standardization of the holy text.

Or. 2165

The British Library manuscript Or. 2165 is another early Qur’an manuscript written in Hijazi script. It consists of 47 folios and is currently housed in the British Library in London. Through paleographic analysis, this codex has been dated to the late first century AH. It shows similarities to the Codex Parisino-petropolitanus but represents the work of a different set of copyists. The British Library acquired the manuscript in 1994 after it was identified by German scholars, and it continues to be an important specimen for the study of the early Qur’anic text.

The Birmingham Manuscript

In the halls of the University of Birmingham lie fragments of one of the oldest known Qur’an manuscripts in existence. Its discovery in 2015 shook the academic community and captured global headlines. This ancient text has become a gateway into Islam’s origins and the history of its sacred scripture.

The fragments first came to the university as part of a larger collection of over 3000 Middle Eastern documents acquired by the Cadbury Chocolate family in the 1920s. For decades they lay mostly forgotten in the university library until a doctoral researcher Alba Fedeli noticed something amiss. The parchment pages seemed oddly bound alongside a later Qur’an manuscript in a different script. Her keen eye set off a chain of investigations that led to radiocarbon dating revealing the jaw-dropping news – these folios were from the seventh century CE, placed within the lifetime of Prophet himself.

The power of this discovery cannot be overstated. For Muslims, the Qur’an represents the divine word of God transmitted to Muhammad. Its origins rest on oral traditions passed down through generations before being compiled into written form. Finding such an early physical copy brings Islam’s foundational stories to life in a profoundly visceral way. It provides a tangible connection to the Prophet’s world when the sacred verses were first etched onto parchment by pious hands.

The manuscript consists of two folios containing parts of Surahs 18 to 20 written in an elegant early form of Arabic script known as Hijazi. This graceful calligraphy flows across the folios with startling clarity given the text’s antiquity. One can almost feel the devotion of the scribe who penned these words centuries ago, dedicating himself to perfectly preserving the holy revelation.

Since its unveiling, the ancient fragments have been subject to extensive study and debate. Researchers have confirmed the radiocarbon dating and analysed the text’s contents and writing style. Some Muslim scholars initially questioned the dating, highlighting the manuscript’s dotted script as proof of it being later. But evidence has verified that early Arabic scripts did sometimes employ dots, though often inconsistently. Minor orthographic variations have also been found between the manuscript and today’s Qur’an, sparking discussions about canonization.

Above all, this precious discovery has reinvigorated interest in the Qur’an’s origins and development in nascent Islam. It provides hope that other ancient manuscripts lie hidden, awaiting discovery by fortunate researchers blessed with providence. Though faded over time, the Birmingham folios shine light onto the fledgling Muslim community in seventh century Arabia who first etched and recited these sacred words, igniting a spiritual revolution for all humanity.