In Last 30 years, Kashmir witnessed killings of thousands of militants, some of them trained by veterans in Afghanistan. But why none of them was born so big in their death as Burhan has, explores Shams Irfan

In April 2018, as Aziz, 55, slowly steps on the raised platform and starts walking towards Hizb-ul-Mujahideen commander Burhan Wani’s grave, located in the corner of Tral’s martyr’s graveyard, a sense of piety overtakes him.

Instantly, he takes his shoes off, folds his hands, and then with his head down crosses almost two dozen militant graves of 1990s, to reach near Burhan’s.

As he stood facing a marble epithet, with Burhan’s name, date of birth, death, rank, and code name inscribed on it, he raised his hands in the air to offer prayers. Minutes later, he was sobbing.

It was a group of seven young men who appeared near the raised platform that Aziz felt interrupted. Soon, the man with salt and pepper beard was seen clearing his moist eyes and calmly moving out to join his family waiting near Eidgah.

“It has been 21 months since he was killed but the rush of visitors has not died,” said cemetery caretaker who helps visitors locate Burhan’s grave. “On an average around fifty people visit his grave daily.” Most of grave visitors are the ones who failed to reach Tral on July 9, 2016, for his funeral.

But those who attended Burhan’s funeral went back home with more than just images of a mammoth gathering. Some of them returned home as completely changed persons, carrying permanent burdens on their souls.

One among them was Basit Rasool Dar, 23, an aspiring engineer from Madhama village in south Kashmir. Son of a banker, Basit turned into a “hermit” once home from Burhan’s funeral. Next three months Basit spent in isolation, which his family took as just another phase in a young man’s life. “I wish I could have understood what was going inside his teenager mind,” said his father Ghulam Rasool Dar.

Then on the evening of October 21, 2016, Basit left home to offer Magrib (evening prayers) in the local mosque and vanished. His mysterious disappearance set a desperate cycle of search by his family, but without any success.

Exactly 53 days later, on December 14, 2016, Basit was killed in an encounter in nearby Bewoora village, ending his father’s search on a tragic note. “I regret I couldn’t notice pain in my son eyes,” said his father Dar.

But Dar was not alone who failed to notice the change in his son once back from Burhan’s funeral.

On July 8, 2016, as the news of Burhan’s killing reached Hajin town of Bandipora, two friends Aabid and Nasrullah, both in their early twenties, locked themselves in their respective rooms to mourn in silence. Next morning, Aabid sneaked out of his room, hitched a ride on a friend’s bike and drove all the way to Tral to attend Burhan’s funeral.

“Once back from funeral Aabid was not the same person,” recalls his father Abdul Hameed Mir.

On May 12, 2017, Aabid and Nasrullah vanished. Their sudden disappearance raised many questions in erstwhile Ikhawan town, given room to rumours.

But five days later, when their picture holding AK47’s rifles surfaced on social media sites along with Lashkar-e-Toiba’s Ayub Lone aka Lelhari, searches and rumours stopped.

With post-Burhan situation blurring geographical lines for new age militants like Aabid and Nasrullah, they chose to start their rebellious journey in south Kashmir.

A few weeks later, when they finally entered Hajin, it was both symbolic and emotional for natives who have lived through Ikhwan rule. Last time Hajin had seen a local militant was in 2005, when Abdul Qayoom Parray, who was killed in Bandipora, was brought home for burial.

After Aabid and Nasrullah’s entry, the erstwhile hometown of government backed counter insurgents like Kuka Parray, Fayaz Nawabadi and Rashid Billa, Hajin was now dotted with Burhan graffiti.

On August 5, 2017, Aabid and his two associates were killed in Amargarh (Sopore), while his friend Nasrullah survived for two more months before he too was killed on October 11, in Rakh Paribal area of Hajin. “It was Burhan’s killing and the aftermath of it that triggered change in Aabid,” said Mir.

But Aabid and Nasrullah’s killing couldn’t stop the chain-reaction that Burhan has set in motion post July 2016.

According to figures revealed by Mehbooba Mufti in state’s legislative assembly in February 2018, 88 local boys joined militant ranks in 2016, compared to 66 in 2015.

The numbers spiked in 2017 – considered as one of the bloodiest years in Kashmir’s recent history – as 126 local boys joined militancy ranks.

IRON FIST

By the time Burhan was lowered in his grave after over two lakh people offered his funeral prayers, Kashmir was literally turned into a battlefield. On one side were angry mourners trying to march towards Tral, the hometown of Burhan, defying CRPF and police obstacles and the use of bullets and pellets to stop them. The mayhem of July 9, 2016, ended on a bloody note with 12 civilians dead, thousands in hospital with pellets and bullets in their bodies, and thousands still on the streets refusing to give up. The policy of crushing civilian protests with ‘iron fist’ soon backfired, sending Kashmir into a long cycle of killings, shutdowns and killings.

But with BJPDP alliance, Mehbooba ended up justifying most of the civilian killings with her crass one-liners like “toffees and camps”.

Between conflicting priorities of ruling partners, Kashmir was left to burn for months. With every civilian killing, pellet dotted face, fractured leg, and tear-gassed street, Mehbooba’s grip on Kashmir started to loosen.

The price of “restoring peace” in Kashmir through the barrel of gun was massive. It took 117 civilian lives, over three thousand pellet injuries, around ten thousand injuries, to keep Kashmir under control.

But as streets protests fell silent for a while, guns started to roar across Kashmir, triggering gunfights inside residential houses and orchards. With “iron fist” policy in place encounter sites became new battlefields for angry youngsters.

In post-Burhan Kashmir, it became a sort of norm for civilians to march towards encounter sites with clear objectives to help trapped militants escape. At a few places, they actually succeeded in getting militants out from besieged spots, but often at a cost of massive civilian causalities. Burhan’s killing marked the death of fear in Kashmir periphery, a phenomenon that no policymakers is able to respond.

BURHAN LEGACY

When Mannan Bashir Wani, 27, a PhD scholar at Aligarh Muslim University (AMU), who lived in Tekipora village of picturesque Lolab Valley, heard about Burhan’s killing, he confined himself into his room. For next two days Mannan was inconsolable. When he came out of his room, there was a visible change in Mannan. Known for his intellect throughout Lolab, Mannan was soon to surprise everyone.

On January 5, 2018, Mannan travelled to Delhi from Aligarh, and vanished without a trace. Two days later, when Mannan’s picture holding an AK47 rifle surfaced on social media, it shocked everyone! Everyone wanted to know how a guy with such a promising career can chose gun?

The answer perhaps lay in those two days Mannan spent in isolation after Burhan’s killing.

Perhaps former Chief Minister Omar Abdullah was never so right in his entire political career when he prophesised that “Burhan’s ability to recruit in to militancy from the grave will far outstrip anything he could have done on social media”.

“The way people reacted to Burhan’s killing was surprising, if not shocking,” said one of Mannan’s friends.

But the question everyone seems to ask is what made Burhan so popular? Was it his social media presence, his looks, his non-controversial stature, or his ability to attract people?

The answers might not be as black-and-white given Burhan’s phenomenal following and cult status. He is perhaps the first rebel whose name was mentioned by Pakistani’s Prime Minister Nawaz Sharief while addressing United Nations General Assembly.

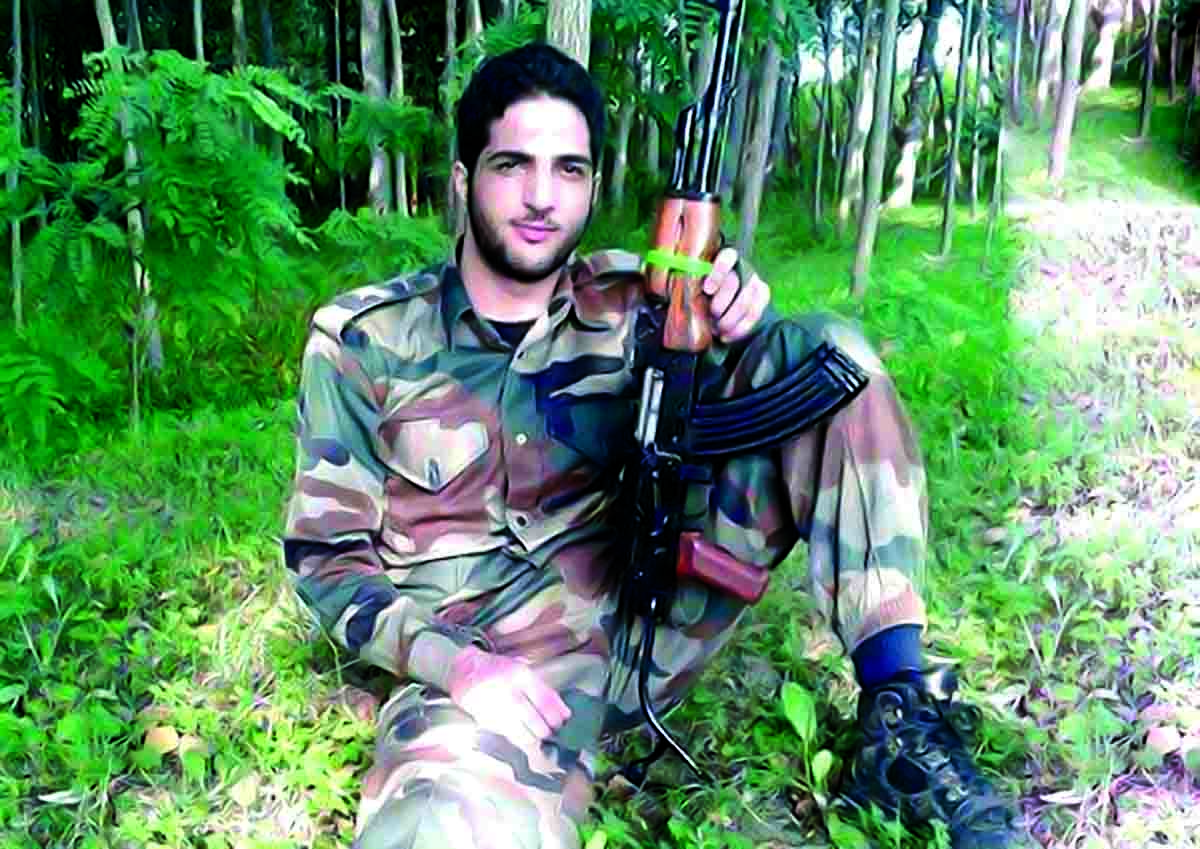

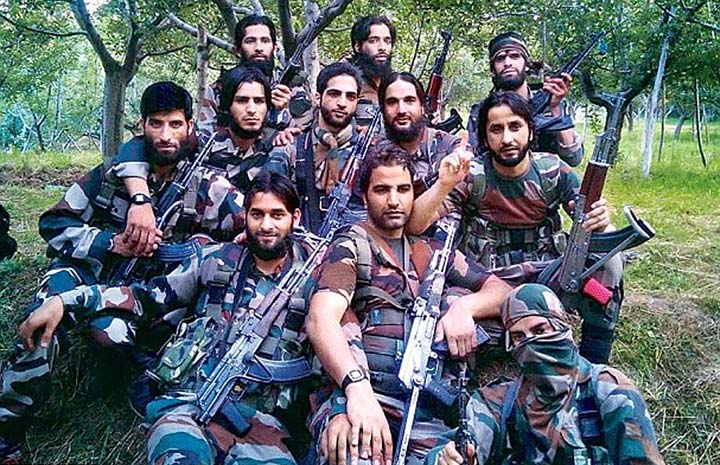

But in Kashmir, long before Burhan became an international headline, he had successfully steered militancy out of foreigner’s hands. He restored Hizb’s assets and image by promoting it as an indigenous force. He unmasked the hooded rebel for the first time. With his boy-next-door looks, and signature AK47, he photographs started to dominate social media spaces in Kashmir. Even after two years of his death, the iconic image of Burhan surrounded by his ten associates is still the only postcard picture of new age militancy. Apart from his online presence Burhan’s ability to attract new recruits in militant folds, even from his grave has baffled security experts.

“Burhan gave new militancy a face, which it lacked since late nineties,” said Azad, a student who wishes not to be named. “There were famous militants back then too, but present generation could hardly relate or remember them.”

To make his point Azad tells how Gurez, a small valley with overwhelming military presence, stayed shut for 21 days after Burhan’s killing. “Since 1990, there has not been even a single protest in Gurez, but it shut to mourn Burhan,” said Azad, who lives in Bandipora.

While other militants eventually faded in time, the aftermath of Burhan’s killing keeps Kashmir on the edge even after two years. Almost every street in Kashmir is painted with Burhan’s name, echoing fallout drenched in blood.

Perhaps that is why Aziz, who has lived through 1990s, was inconsolable when he finally reached Burhan’s grave.