Written on August 2, 1870, this piece offers details about the ‘pride of possession’ when Britons came visiting Kashmir. Shedding light about the court and the courtiers, it gives a sketch of life, the games the exploitative royals played and the armies they raised

The Hurri Purbut, or fort of Srinuggur, overlooks the city. Built on the ridge of an abrupt and rocky hill about 250 feet high, this long rambling edifice has a picturesque look, and reminds you of Edinburgh Castle with a difference. A massive wall surrounds the base of the hill, and over one of the gates an inscription in Persian states that it was built by “The Chief of the Kings of the World, Shah Akbar may his dominions extend, at the expense of one crore and ten laks of rupees, from Hindustan.”

Vigne, little anticipating that Kashmir, soon after his prediction, would fall into the power of Great Britain by the chance of war only to be immediately disposed of to a native chieftain, thus expressed hopes not destined to be realised.

“One of the first results of the planting of the British flag on the ramparts of Hurri Purbut would probably be a rush of people, particularly Kashmerians, to the valley in numbers sufficient for a time to affect the price of provisions. The next would be the desertion of Simla as a sanitarium in favour of Kashmir.

The news of its occupation by the Queen’s troops in India would spread through the East with a rapidity unequalled; it would be looked upon as the accomplishment of the one thing needful for the consolidation of the British power in Northern India.

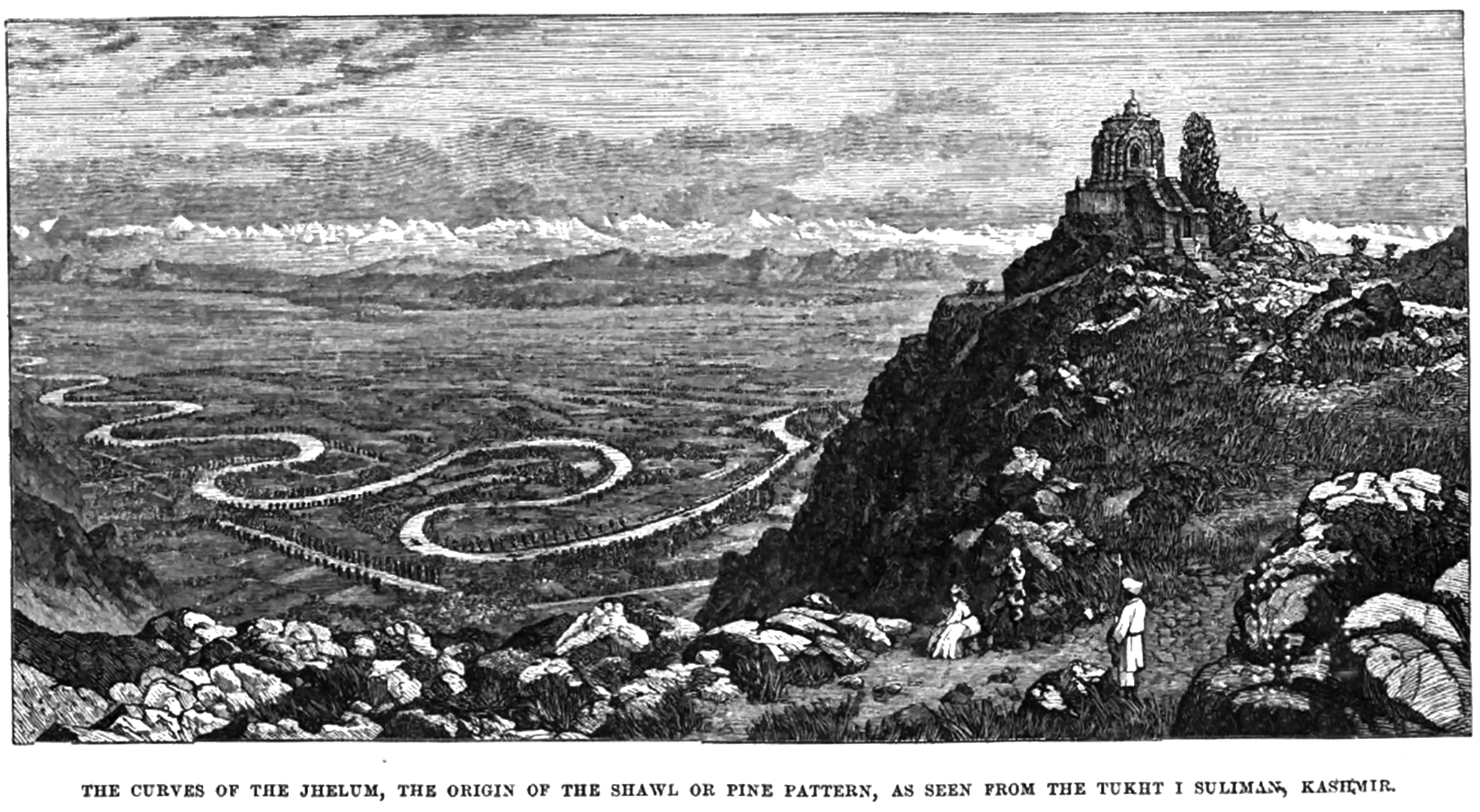

When a road is made through the pass from Bara Mula, an army of any strength and most perfectly appointed may be marched in from four to six days from the healthy atmosphere of Kashmir to defend the passes of Attok or Torbela; and with such protection on the north, Bombay, as the capital of India, on the south, and the Indus between them, the British possessions in Hindustan ought to be as safe from foreign invasion from the westward as such an extended line of frontier can possibly be made to render them. But Kashmir not only deserves attention as a stronghold in time of war; it is to the arts of peace that this fine province will be indebted for a more solid and lasting, though less gorgeous, celebrity than it enjoyed under the Emperors of Delhi. The finest breeds of horses and cattle of every description may be reared upon its extensive mountain pastures, where every variety of temperature may be procured for them; its vegetable and artificial productions may be treated with British skill and capital in such a manner as to ensure an excellence equal to those of Europe, and superior to that of the neighbouring countries.

Kashmir will become the focus of Asiatic civilization, a miniature England in the heart of Asia. The climate will permit the introduction of the sports and games of England, and presenting so many attractions, it will become the sine qua non of the Oriental traveller, whether he be disposed to consider it as the Ultima Thule of his voyage, or a resting-place whence he may start again for still more distant regions.”

The Lieutenant-Governor of the Punjab, Sir Henry M Durand, paid the Maharajah a visit. His arrival was looked for with much interest, not only by the Europeans, who expected he would put an end to the exclusion of foreigners from the valley during the winter months, but also by the Maharajah and his court, which is mainly composed of the ruling Hindoos, and who were in the greatest state of apprehension as to what the object of the journey could be. He arrived in a splendid boat, rowed by thirty men; and fitted up with a large gaily painted pavilion; but as the roof was flat, and he desired to have a good view, he sat on the top of it.

The Maharajah joined him outside the city; and over them attendants held long-poled umbrellas of scarlet and gold.

The many handsome boats, and the large muster of Kashmirian dignitaries made the sight a brilliant one, of its kind. During the ten days of Sir Henry’s stay, salutes were constantly fired to announce to the world the visits and return visits of the great, and every afternoon the Maharajah repaired to his father’s tomb, where he remained some time seeking from him strength and counsel. The Maharajah gave two dinners to Sir Henry to which all the European residents were invited; gentlemen to the first, and ladies and gentlemen to the second, the only occasion on which he has received any members of the fair sex.

The first was given in his town palace, situate on the river and alongside his temple, or chapel royal, which is roofed with plates of gold.

The invitation, written on a large sheet of paper, addressed generally to the residents of Srinuggur, to most of whom it was presented, was worded as follows; and those who accepted it signed their names below.

“His Highness the Maharajah requests the pleasure of the company of the gentlemen at Srinuggur and its vicinity, to dinner at the palace to-morrow evening at eight o’clock. His Highness further desires me to say that, as he is given to understand that some gentlemen are not provided with undress uniform or evening dress, this part of the ceremonial will be waived; and His Highness will be happy to see such gentlemen in morning attire. As each gentleman arrives he will be introduced to the Maharajah by the Resident.”

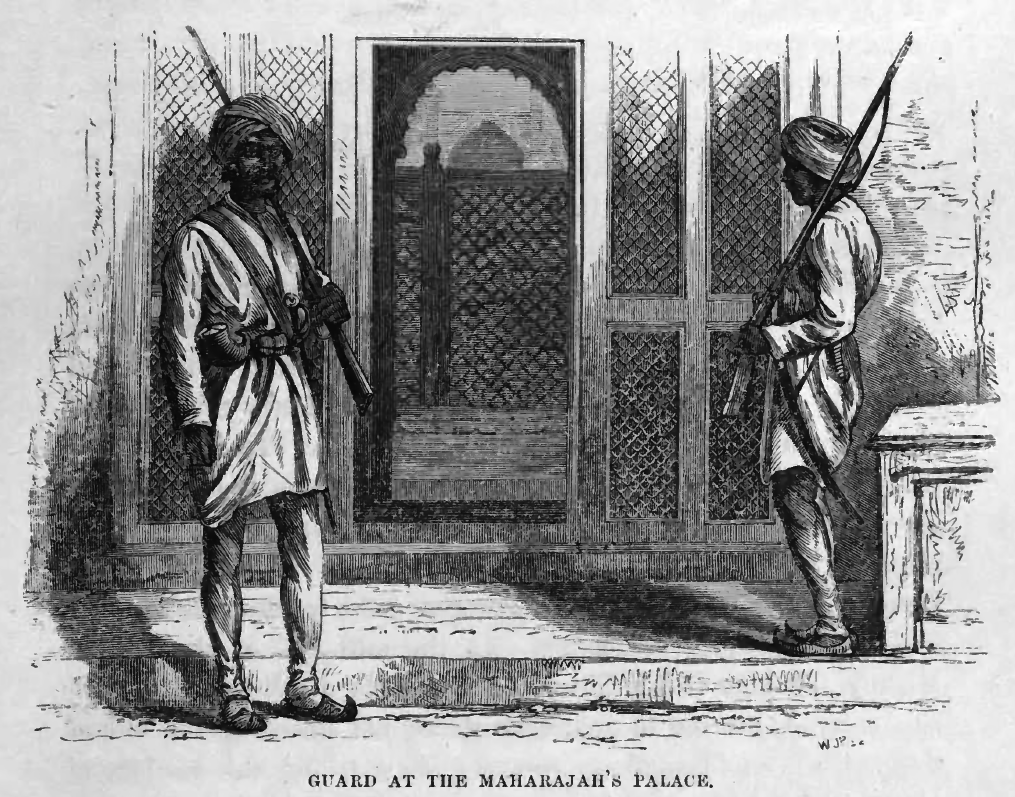

The dinner took place at nine. The bridges and opposite bank of the river were illuminated in a primitive but effective manner by numerous large boats drawn up close to the bank, having scaffoldings three or four storey high erected on them, covered with innumerable little oil lamps, which lighted up strange efforts of native art in the shape of hobgoblins and other designs of a more or less demoniacal character. A rude massive wooden staircase lighted by flaming torches held by soldiers, is the only approach to the palace from the river-side. Ascending it, a short passage leads to a large court-yard lined with troops, whence you make your way to the grand entrance, where the body-guard present arms.

Entering the hall you are greeted with a loud “Salaam, sahib,” to which you reply “Salaam”. The baboo in waiting forthwith conducts the guest to a large and wide balcony fronting the river, at the further end of which are seated the Maharajah, Sir Henry, and the Prince, who rise and bow as each arrival is presented. On the river, in addition to the lighted scaffoldings and bridges, a fleet of canoes covered with small lamps performed various evolutions, paddling with much dexterity.

To beguile the mauvaise quart d’heure two nautch-girls danced in the centre of the apartment, wriggling, waggling, and moving slowly round and round, waving their arms, rolling their eyes, and repeating the same evolutions till dinner was served; but of ballet-girl sensationalism there was none. They were enveloped in a cloud of spangled gauze, silk trousers, and showy jewellery.

Stupid and uninteresting as these nautches are to foreigners, they are a source of supreme delight to the people of India, whether Muhammedans or Hindoos. The latter have troops of them attached to their temples, where they assist in the sacred rites. A burra khana and a nautch is the ambition of the poor, who save up their earnings for the festival, while the rich can do no greater honour to their guests, than by exhibiting their private nautch-girls.

We have entered the great hall brilliantly lighted with coloured lamps, and glowing with devices of the shawl pattern, printed on its ceiling and walls. The Maharajah led his chief guest to the seat of honour, and retired to a balcony, where he watched the proceedings from behind a screen.

Toward these dinners His Highness contributes the eatables and drinkables, but cooking is done by the Resident’s chef, or by those of other Europeans, and the plates, knives, glasses, all the properties are brought by the guests themselves. Each man brings his own servant who looks sharply after his comforts, and yet more so after his table furniture. Some of the visitors returned minus their silver mugs; the neighbouring servants watch them rise, and pocket them on the instant.

The dinner was well laid out, the hall brilliantly lighted, and the guests, nearly all officers, were full of expectation of Sir Henry’s speech, which was to fulfill hopes that the valley would be open to Europeans in winter, and consequent sport in Kashmir.

Sir Henry, a stalwart man, and in youth a dashing officer, has long been considered one of our ablest Indian administrators… Dinner over, Sir Henry proposed the toast of the evening the Maharajah of Kashmir. At the outbreak of the Indian Mutiny the late Golab Singh, then on his death-bed, enjoined, nay ordered, his son to proceed with all his troops to the aid of the British, an injunction promptly obeyed, and the soldiers of Kashmir fought by our side at the siege of Delhi. From the late Maharajah and from the present ruler Englishmen had received unvarying kindness and hospitality. In no country were they treated with greater, or perhaps equal consideration. He asked the officers round him whether, even in India, they met with the same prompt attention to their wants, the same quick despatch, or whether kulis were supplied to them with the readiness that distinguished Kashmir, a remark much applauded, as there have been loud complaints on this subject in India. Sir Henry concluded a complimentary and diplomatic speech by saying that the Queen had no subject more loyal than the present Maharajah, and called on Colonel Gardiner to reply.

The colonel, one of the most extraordinary men in India, has from his boyish days gone through adventures of every romantic and daring character. Probably from this fact he took the fancy of Golab Singh, forty-five years ago, by whom he was appointed commarider-in- chief of his forces, a post which he has held uninterruptedly till the present time.

Now a strong hale man of eighty-five, his uniform is a large green and yellow tartan plaid, puggery and trousers. He replied briefly, and ended by saying that he had been present at the late Maharajah’s death, whose last words to his son were, “Should only one Englishman be left in the world, trust in him.” Some present were disposed to think this concluding sentence an embellishment of the gallant colonel’s invention.

The young prince, in his father’s name, thanked Sir Henry for his speech. The company then withdrew to the balcony, and dispersed by boat to their camps or bungalows. Sir Henry threw no light on the subject which has so deep an interest to Indian visitors; but a few days afterwards it oozed out that His Highness had consented to the establishment at Islamabad of a sanitarium for British soldiers, and that six hundred men were to come, as soon as the arrangements were completed. Thus the thin edge of the wedge will be inserted.

Two days after the banquet the Maharajah held a review of his army in a fine parade ground, not unlike the race-course in the Bois de Boulogne. Seats were provided under an awning for the European visitors, and the troops, in number about five thousand, marched past. The main body of the infantry wore an imitation of the British uniform, scarlet coat and white trousers, with scarlet and white puggery. But the most picturesque regiment was formed of Balkans, from Baltistan, Little Thibet, the capital of which is Iskardoh. Their uniform consists of a large double-cornered scarlet cap, which, when on, has a most extensive look, and when off, folds down flat, jacket faced scarlet, with dark green sleeves, a kilt, light green knickerbockers, crimson woollen leggings bound round with different coloured cords and bare feet. They are armed with the old Brown Bess, and carry their ammunition in pouch boxes, made of papier mâché. Not the least singular feature is their long, silky, black hair, curling in ringlets down to the waist.

Most classes of Muhammedans shave their heads completely, and from youth to age never allow the hair to grow more than a few days. Yet many old men have very little hair left to shave. The troops under the command of Colonel Gardiner are executing various evolutions with considerable dexterity. The words of command are given in English, which sounds strange. Two regiments have formed a square to receive cavalry, with small field-pieces at the angles; and the ammunition in the centre.

They are loading, when one of the gunners lets his fusee fall on the powder-bag, but catches it up and hurls it into the square. The ammunition waggon explodes, and so do most of the papier mache pouches, in which the men carry their cartridges or loose powder. As the smoke clears away, the plain is seen covered with running, burning figures, tearing off their clothes, falling and rolling in pain as though on a field of battle. Unprovided with medical stores, the native doctors attempted, but in vain, to relieve the worst sufferers, and the cavalry dashed off, quickly returning, each man bearing a sheep before him. These animals were at once killed, and their blood poured over the wounds of the sufferers, but no benefit could be derived from the process.

The hospital, which had been empty in the morning, was quickly filled. The Maharajah immediately left the ground; first, to consult his spiritual adviser, and then to visit the survivors in the hospital. Fourteen men died that evening, but no information could be afterwards obtained, as the matter was hushed up by orders from head-quarters. Another day was devoted to boat races in honour of Sir Henry. The Maharajah’s boats contended, each rowed by thirty men, and there were several races between Englishmen.

Another day to Polo, or hockey on horseback, a favourite game among the chiefs and nobles of Asia. The game of Chaugan is explained by Abul Fazl in the Ain i Akbari, as the Emperor Akbar was proficient in it, and played, not only by day, but at night, when fire balls were used.

“Superficial observers look upon this game as a mere amusement . . . but men of more exalted views see in it a means of learning promptitude and decision. It tests the value of a man, and strengthens bonds of friendship. Strong men learn in playing this game the art of riding, and the animals learn to perform feats of agility and to obey the reins. Hence his Majesty is very fond of this game. Externally it adds to the splendour of the Court; but viewed from a higher point, it reveals concealed talents . . .

There are not more than ten players, but many more keep themselves in readiness. When one ghari (twenty minutes) has passed, two players take rest, and two others supply their place.

The game is played in two ways. The first is to get hold of the ball with the crooked end of the chaugan stick and to move it slowly from the middle to the hal (the pillars which mark the end of the playground). This manner is called in Hindi rol. The other consists in taking deliberate aim and forcibly hitting the ball with the chaugan out of the middle; the player then gallops after it quicker than the others, and throws the ball back. This mode is called belah, and may be performed in various ways. The player may strike the ball with the stick, in either hand forwards or backwards … in any direction, or he may spit it when the ball is in front of the horse . . . His Majesty is unrivalled for the skill which he shows in the various ways of hitting the ball; he often manages to strike the ball when in the air, and astonishes all.

When a ball is driven to the hal they beat the naggarah, so that all that are far and near may hear it. In order to increase the excitement betting is allowed … If a ball be caught in the air, and passes, or is made to pass, beyond the limit (mil), the game is looked upon as burd (drawn). At such times the players will engage, in a regular fight about the ball, and perform admirable feats of skill.

“His Majesty also plays at chaugan in dark nights, which caused much astonishment even among clever players. The balls are set on fire . . . polos wood is used which is very light, and burns for a long time. For the sake of adding splendour to the games, which is necessary in worldly matters, His Majesty has knobs of gold and silver fixed to the top of the chaugan sticks. If one of them breaks, any player that gets hold of the pieces may keep them.”

Finally, his Highness gave a grand dinner-party to all European visitors, the first to which ladies had been admitted; but we live, as Mr. Disraeli says, in times of transition. The entertainment took place in a garden called the Nishat Bagh, on the margin of the Dhul Lake the favourite haunt of Lalla Rookh and Feramorz.

The garden, situate at the head of the lake, and base of the mountains, rises in a series of ten terraces, the upper three being eighteen feet in height, one over the other. From tanks filled with fountains on every terrace a stream runs down the centre of the garden, and along inclined walls of marble cut into various shapes to diversify the form of the wave and lessen its sound.

“When the waterfalls gleam like a quick fall of stars,

And the nightingale’s hymn from the isle of Chenars

Is broken by laughs and light echoes of feet

From the cool shining walks where the young people meet.”

Pathways of green turf, o’erarched by ancient trees of the time of Akbar, lead to an open pavilion, through the centre of which runs a crystal stream, brought through a passage from the springs of the mountain hard-by, and crossed by slabs of marble. The dinner was at nine. The road to the garden was through the Apple-Tree Canal, the floating gardens, the city lake (with its limpid waters covered with rose-coloured lilies), and past the Isle of Chenars, from which might perhaps have been heard “the nightingale’s hymn.” The garden was illuminated with rows of lamps along the several terraces, and on the landing stage a guard with lighted torches received the guests. Soldiers and torchbearers preceded each of them to the tenth terrace, where, under a large awning, sat the Maharajah, and the Lieutenant-Governor of the Punjab. A nautch was progressing. Thirty women were present, only a few of whom took part in the performance, which was in the style before described; but varied by a single-stick encounter between two of the girls. The scene was brilliant, and the cool shining walks glittered with a profusion, if not with the “hundred thousand” lamps of Vauxhall. After nautch, dinner.

Then walk, see the fireworks, smoke, and depart.

(This essay was excerpted from Letters From India And Kashmir, a book that George Bells and Sons published in 1874, almost four years after it was written. It is widely believed that the book was authored by J Duguid in 1870 and was annotated in 1973 by H R Robertson and W J Palmer. Illustrations used in this copy belong to Robertson.)