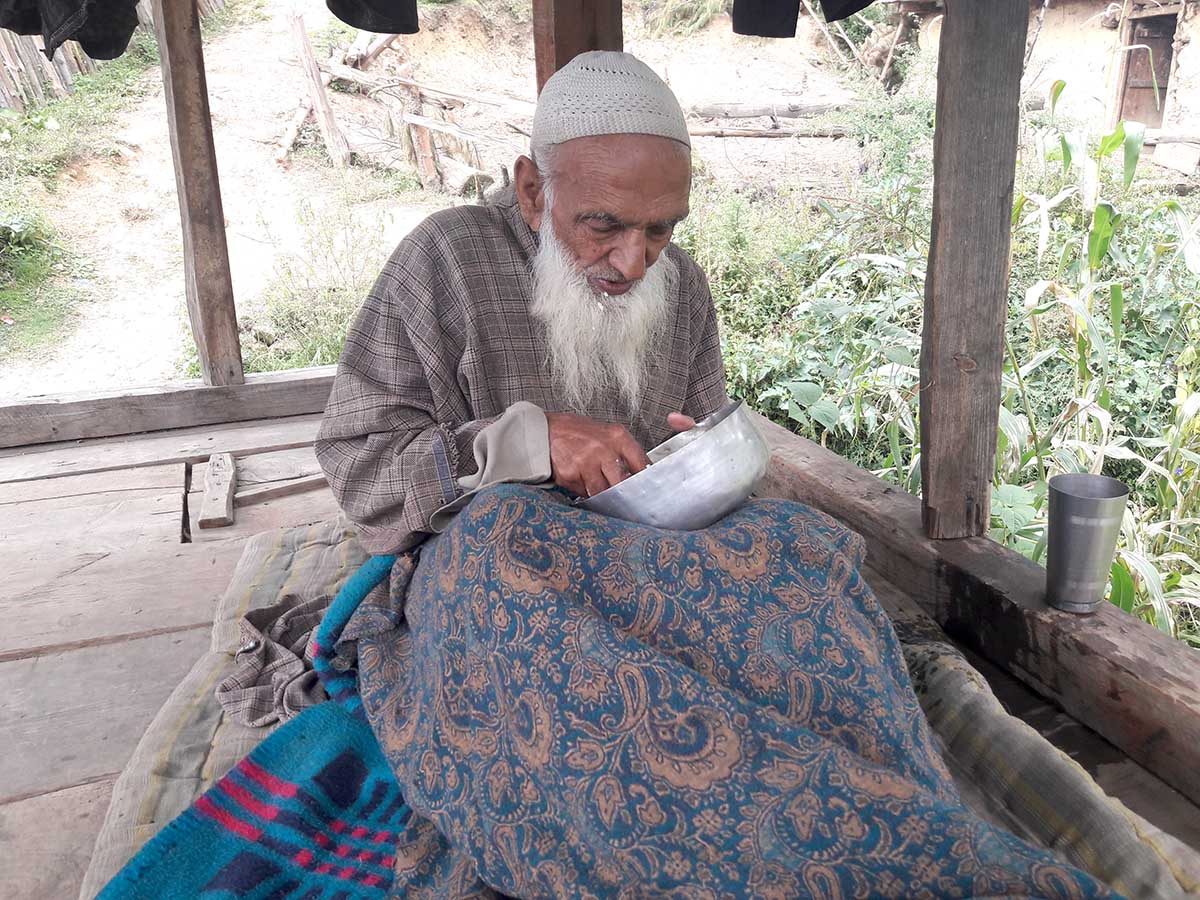

Deep South in a sparsely populated hamlet overlooking Shangus is a man who has lived a century and never used a vehicle. He knows the forests of India and Pakistan but has now started forgetting things, report Umar Khurshid

Lassa Khan is unsure of his age. “I can be either 105 or 110,” he said. “I don’t remember accurately.”

A professional shepherd, Khan lives in a single storey mud house on the summit of a mountain in Brimmer-Nurser in south Kashmir’s Shangus belt. He is always surrounded by his three generations in the Gujjar Basti, located slightly away from the main village.

Incoherent and weak in his memory, Khan, however, remembers certain things. In 1945, for instance, Lassa said, he was married to Tooti Begum of nearby village Ranipora. At that time, Jammu used to be the second home for all Kashmir’s cattle herders during winters. “After I got married to Tooti, I stopped going outside,” Lassa said.

The old Khan says those were good days of Kashmir. “Earnings were less but people were living independent lives.” Sitting in the elevated space on his old style, wooden rice granary, Khan said that India and Pakistan were not separate and the British were ruling the entire region. “Rulers were treating subjects with respect,” he said. “This was despite that the British people would not be around always.”

“I used to roam all around India and Pakistan then with my flock and the associates,” Khan said. “Nobody would stop you anywhere. One year you decided to take your flock to one mountain range and next year you could go to other side. But now you even need permission to move from one district to another.”

Khan said he has even spent months in desserts in Pakistani areas with his herds. But what he specially remembers is the abject poverty. “There was no proper food,” he said. “I have survived on corn chapattis for decades.”

Those days, he said, clothing was simple and rare. “A person used to be called a rich if he owned trousers,” Khan said. “When my cousins got married, we paid a rent (in the shape of corn) to get a Shalwar for a day.”

Khan’s routine was Pulhood, (a grass slipper) for decades during winters. In summers, he said, he used to walk barefoot. “Many times I travelled to Jammu barefooted,” he said.

One thing which is very interesting about Khan is that he has never travelled by any mode of transport till he turned 90. Later, due to the old age and weakness his son Sooba used to take Khan in a private vehicle to see a doctor or to a relative or acquaintances, occasionally.

Khan also remembers how during the reign of Maharaja Hari Singh, his government would send the residents to Beagaar, the forced labour. Muslims used to plead with the Pandit’s – who mostly were running the government, to release them from Beagaari and ultimately Pandit’s held all the rice-fields of Muslims in lieu of this concession.

“At the end of the day all the land belonging to Muslims was occupied by Hindus rulers,” recalls Khan. “It was really very difficult to purchase grains during those days. Though it would cost Rs 3 for a Kahrwar (80 kgs), but only one out of every 100 persons could afford purchasing that.”

People lacked an idea of a paper rupee, actually, Khan said, they knew only coins. In Ranipora, where his brother in law Haji Shah Wali Khan lived, Khan said Wali once gave one rupee note to his sister Paadshah Biwi, for safe custody. “She mistook it for a piece of paper and threw it away simply because she did not know it was money, she only knew coins were money,” Khan said. “She had never seen a paper currency note.”

Khan also remembers that one day, when he was with his uncle Mishri Khan, and they were moving with their flock, they came across an unusual sight. “We saw a long line of people who were waiting in a queue to get their letters read and written by a well-dressed man,” Khan said. “He was perhaps an English man.”