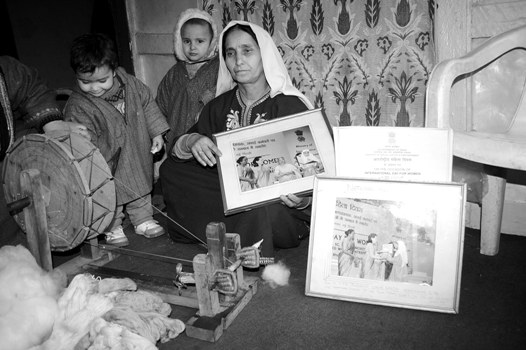

Left to fend for her six children after her husband‘s death Khatija turned to the spinning wheel. Weaving a living, she ended up empowering hundreds of other women. Ibrahim Wani reports.

For Khatija the wheel is a symbol of survival. For thousands of others Khatija is a symbol of inspiration. She spends most of the day at the spinning wheel earning a livelihood for herself and her six children. Khatija did not know how to spin yarn until her husband died and she along with her children was thrown out by her in-laws.

Khatija Begum spent a quiet childhood in a village in Sangam, Islamabad. Married at an early age, she came to Basantbagh Srinagar as a young bride and settled with her husband at her in-laws. Her husband ran a Kiryana store, which was the only source of their livelihood.

However fate soon caught up with her. Unexpectedly, in 1991 her husband died leaving Khatija all by herself and the responsibility to look after their six children. Soon after the death of her husband, her in-laws threw her out of the house and on to the street.

“I had no idea what to do? How to survive? I had six children to take care of,” Khatija recalls. Her in-laws sold the house and did not give her any share.

With nowhere to go Khatija found refuge in her brother’s residential quarter in the same area. Though her brother provided the shelter she had to earn a living to feed her children. It was at that time the spinning wheel became her companion. She learnt to spin yarn from a lady in her neigbourhood.

The lady introduced her to merchants from where she would purchase Pashmina and also taught her the nuances of the trade. She realised quite early that it was difficult for a single woman to survive in this world.

“I would get Pashmina from the merchants and spin for as much time as I could,” says Khatija. She would spin as late as 4 am in night without stopping. “This was the only way I could take care of my children’s needs,” she says. The work would fetch her 1500 to 2000 rupees a month with which she would make her ends meet. “I was able to feed my children and pay their school fees”.

After seeing the pain of suddenly turning destitute, she would readily help other women in need by training them or providing them the raw material for spinning. Taking inspiration from her the women in the neighbourhood realised that they could earn a respectable living and supplement their family incomes working on their own.

Khatija was more than helpful. Not only did she train them to spin but she would arrange the raw pashmina for them. “The women would find it difficult to leave their households and deal with the merchants”.

Most of the women who came to her were either widows or those belonging to the lowest income group. The number of women coming to her started increasing as the conditions worsened in the valley.

“Having faced difficult times myself I could understand the plight of these women. Most of these women are in desperate need of money and through this skill they found a way to earn” says Khatija.

By working with Khatija, the women would be spared the vagaries of nagging middlemen. Besides, the women found it quite comfortable to deal with Khatija instead of the merchants. She says, she does it on a purely non-profit basis.

Over the course of time women from other localities started approaching her. Their number kept rising. At present around 3000 women receive raw material through Khatija. They come to her from as far as Uri and Shopian. “Women come to me with high expectations. For many women this is the only way to run their families,” she says. As she narrates her tale a number of women form the neighbourhood crowd around. They call her ‘Bhoba’- the mother.

Many times she has helped the women from her own meagre savings. “Women come here from far off places with a hope and it is crushing for them if they go empty handed. The merchants never pay up in full. If I go to them with a work of 5000 rupees all I get is Rs 2000 and the rest is witheld for future transactions.”

Morover, she also lends the women, who come to her, a patient ear and gives them hope. “A number of women have family problems with no one to share with and get support from. I just lend them some emotional support and advice so that they can carry on,” Khatija says.

Khatija was awarded for Women empowerment in 2005 by the ministry of social justice and empowerment. The award was presented to her by Sonia Gandhi and Miera Kumar at Delhi.

Though she turned an adversity into an opportunity and on the way helped others as well, she rues the fact that in spite of the award no help has come her way. In twenty years of her struggle she is yet to have a house of her own.