Market forces may have to rework Kashmir’s woodworks sector so that the main producer, the artisan is not pushed to a disadvantage, writes Peer Faizan Bashir after investigating the craft eco-system for his academic requirements

“The destruction of the old five-story wooden palace of Srinagar during Harsha’s reign marked a turning point in the history of woodcraft in Kashmir. From 1028 CE onwards, the region witnessed a flourishing of woodcraft, fuelled by the abundant resources near the river Vitasta,” historian PNK Bamzai records in his history of Walnut Wood Carving. “This resurgence gained momentum under the Sultans, possibly driven by the need for larger structures for Muslim worship. The adoption of the Saracen style, primarily for mosques and tombs, suggests a significant foreign influence introduced by Islam to Kashmir’s architectural traditions.”

Wood carving in Kashmir thrived under Zainulaidin, aka Budshah’s patronage, drawing master artisans from Samarqand, Bukhara, and Persia during the Muslim period. He provided amenities to foreign craftsmen, popularising their art among Kashmiris. The art received a significant boost under the Sultans, with mosques mainly constructed of wood.

The shrines of Khanqah-i-Mualla and Sheikh Hamza Mukhdum Kashmiri exemplify the craftsmanship. A speciality known as Khatamband involves intricate designs using thin slices of pine wood, noted by Sir Walter Lawrence for producing “beautiful ceilings of perfect design, cheap and effective.” Modern examples of Kashmiri woodwork, including ceilings, can be seen in the Naqshband Sahib shrine. (see Historical Introduction of Wood Carving Industry in Kashmir by Azad Rashid Sheikh.)

Budshah commissioned the construction of a magnificent wooden palace in Nau-Shahr, boasting twelve storeys with fifty rooms, halls, and corridors. This palace, adorned with a golden dome and spacious halls lined with glass, exemplifies the grandeur and architectural excellence of Kashmiri craftsmanship under the Sultan’s patronage. (Handicrafts and Kashmiri Artisans during the Mughal Period by Sameer Sofi.)

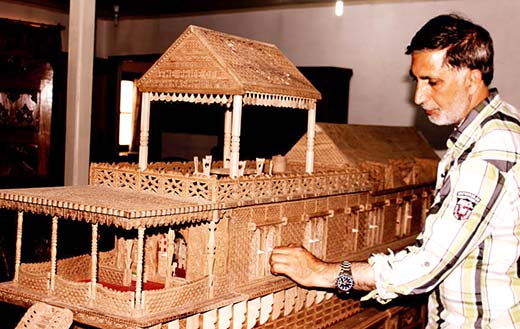

Wood Works

Many mosques and Kashmir shrines were either made entirely of wood or finely decorated with wooden elements. Wooden architecture featured prominently in the construction of roofs, balconies, verandas, arcades, porticoes, panelled walls, and painted ceilings, showcasing the versatility and aesthetic appeal of wood as a structural and decorative material.

The delicate workmanship and attention to detail, including the imitation of wood veins, contribute to the beauty and perfection of Kashmiri woodwork. The fame and reputation acquired by Kashmiri artisans in wood carving, panel making, and other crafts are attributed to the adoption of Central Asian patterns and techniques.

Artisans introduced innovative techniques, including latticework (Pinjarakari) and geometric patterns (Khatamband), which added charm and elegance to architectural structures. Despite the passage of time, Pinjara and Khatamband have survived, demonstrating the enduring legacy of craftsmanship passed down through generations. Artisans continue to innovate and adapt these techniques, incorporating floral motifs and painting to enhance the beauty of wooden panels and ceilings.

During Mughal Occupation

The wood carving industry during the Mughal occupation, as noted by Bernier, was flourishing. In his Kashmir and Political History of Kashmir, Bernier remarks, “The workmanship and beauty of their bedsteads, trunks, inkstands, boxes, spoons, and various other things are quite remarkable, and articles of their manufacture are in use in every part of the Indies. They perfectly understand the art of varnishing, and are eminently skilful in closely imitating the beautiful veins of a certain wood, by inlaying with gold threads so delicately wrought that nothing seems more elegant or perfect.”

The woodcraft industry was not only valued for its aesthetic appeal but also for its economic contributions. Trade and transportation heavily relied on boats, with thousands of them in use for both commercial and general purposes. The Mughal rulers recognised the importance of this industry for facilitating trade and transportation networks, contributing to the overall prosperity of the region.

Mughal emperors considered Kashmiri handicrafts, including wooden articles, as prestigious items suitable for exchange as honorary gifts. This recognition elevated the status of Kashmiri woodcrafts and ensured their continued production and patronage by the royal court.

Since the building industry during the medieval times changed over from stone to timber, the carpenter was in great demand and seems to have commanded a market in the bordering hill states as well.

In Dogra Misrule

During the Dogra rule in Kashmir, the wood-carving industry experienced significant growth, with approximately 50 wood-work factories recorded in the 1921 Census. These factories specialised in carving, Pinjara (latticework), and panelling, often incorporating designs inspired by German, Egyptian, and Swiss styles, as well as sculptures of animals like elephants, dogs, and horses.

Despite being a predominantly Muslim community, wood carvers embraced secular designs, despite potential conflicts with religious beliefs. The industry operated as a cottage industry, with workshops run by master craftsmen who obtained orders from middlemen firms and supervised apprentices. While some workers began investing their own capital in the 1930s, limited resources hindered significant expansion. Products such as tables, desks, trays, boxes, and chairs showcased intricate carvings, reflecting a growing demand for decorative and utilitarian items.

Travellers like TR Swinburne and Sir Francis Young-husband praised the skill and ingenuity of Kashmiri artisans, underscoring the industry’s modernity and excellence.

The Khatamband ceiling of Srinagar garnered such admiration that a few were even exported to England during the Dogra rule in Kashmir. This era marked the genesis of modern wood carving, with intricate designs applied to various articles of daily furniture.

Dr A Mitra, a prominent minister of Maharaja Pratap Singh, organised an exhibition showcasing Kashmiri arts and crafts, further boosting the wood carving industry. Singh personally presented a wood-carved gate and frontage of the Kashmir camp to King George V during the Coronation Durbar in Delhi, promoting Kashmiri wood-carving among the British aristocracy.

Wealthier individuals both within and outside Kashmir extended their patronage to the artisans, leading to the evolution of new designs by famous craftsmen like Ustad Sultan Muhammad Buda. According to the Report on Economic Survey of the Wood-Carving Industry in Kashmir, Ustad’s contributions were highly esteemed, as he established a workshop and engaged workers, although some later left to start their own ventures.

What Is Wood-Work?

Woodwork is an intricate process of creating ascetic designs on wood, especially walnut and particularly the Juglans Regia species. Different parts of the tree, including branches, trunk, and roots, offer varying colours and grain patterns, with wood from the roots being the most prized for its durability and distinct dark colour.

Craftsmen (Nakash) etch floral or other patterns through a dexterous use of mallet and chisel on wood. Wood carving is done on a variety of objects ranging from furniture (tables, chairs, writing desks, dining tables) to articles of personal use like jewellery boxes, photo frames and various other articles used for interior decoration. The artisans imbue their craft with spiritual symbols and motifs. This includes motifs such as lotus flowers, iris flowers, Chinar leaves, grape vines, and animal motifs, reflecting the rich cultural tapestry of the region.

The work is usually done in Karkhanas, which a Ustad (master) presides over. The Ustad is distinguished by its expertise and ownership of means of production.

Karigars (skilled workers) work under the Ustad, with each specialising in different aspects of the craft. Novices learn walnut wood carving through apprenticeship, observing and imitating their masters. Apprentices start with peripheral tasks before progressing to carving. They learn about tools, raw materials, and techniques such as drawing designs on wood. Different roles within the craft, such as carving, carpentry, and polishing, require distinct skills and knowledge. Becoming proficient in carving typically requires a longer apprenticeship compared to other roles.

The craft is traditionally male-dominated. Social norms and physical requirements of the craft, such as strength and posture, contribute to this gender divide. The socialisation within wood-carving Karkhanas reinforces masculinity, with activities like singing, discussing politics, and hosting male acquaintances and customers. These norms and practices create an environment perceived as unsuitable for women. Finished products from the Karkhanas enter the market through various channels for circulation.

A Practitioner Speaks

Nazir Ahmed Khan has been engaged in the profession for the last thirty-five years. The artisans work in and around Chachabal, Safakadal, and Norbagh. Nawabazar, Fatehkadal, Gojwara, Rajourikadal, and Noorbag localities in Srinagar. Noorbagh, however, is the centre of the woodwork. People belonging to the Najar caste are usually the wood carvers. Nevertheless, there are people from other castes, such as Khan’s and Shah’s, who are associated with this craft.

The process that leads to the finished product of Walnut wood could be summarised in points below:

An aged walnut tree is axed and cut into desirable pieces on a band saw. Left for yearlong sun-drying, its bark is removed with a Randi.

A carpenter shapes the pieces of wood into different articles: Bed, Sofa, Table etc, and temporarily fixes them together with nails. The product, thus, reaches the wood-carver (Naqshgaar), who engraves the wood with chisels and creates different designs, including, Chinar, Grapes, Pear’s, Apples, Snakes and so forth.

A carpenter shapes the pieces of wood into different articles: Bed, Sofa, Table etc, and temporarily fixes them together with nails. The product, thus, reaches the wood-carver (Naqshgaar), who engraves the wood with chisels and creates different designs, including, Chinar, Grapes, Pear’s, Apples, Snakes and so forth.

There are two types of craftsmanship: Kashmiri and Punjabi, the latter being costly, time-consuming, extremely intricate, is down to minute details. Different designs are carved into wood: Horses, Bears, Hookah, Harvesting scenes, and even from the Mughal soldiers.

The chisels, and mallets, of varying sizes the artisan procure from Rehbaab Sobun, an area in old Srinagar city. Sebargi, Aaarwouel, Advatith, Watith Narweol, Bod Nariweal, Lokut Nariwoel are some of the instruments used in carving.

After creating designs by first carving to reveal the cloaked lower skin (Zameen Kadun), then creating lines and designs (Guzar Dun), and polishing, the product gets shifted to the carpenter again. The carpenter joins the pieces of wood back into the bed, and chair, and polishes it.

Issues

Khan, the walnut woodcarver, said the dealers sell the products at high rates leaving the artisans high and dry. He said the dealers, expert craftsmen and mediators, get the most of the artisans’ products, creating an economic bipolar divide: elites gaining more money leaving the poor artisan with a few bucks.

Besides, they pointed out that the cheap labour work done by non-native seasonal labour for their elite craftsmen impacts the level playing field for the artisans.