Water-abundant and energy- deficient J&K’s first major leap into the lucrative energy sector was in 1999, when the resource-scarce government started implementing Baglihar with a petty bank overdraft. Sixteen years later, it’s Rs 8713 crore investment made it the proud owner of a 900-MW hydropower project. In between, however, the project managers encountered a series of crises but succeeded in surviving unscathed and with a credibility that can now help J&K build multiple Baglihars. Masood Hussain reveals the hair-raising story for the first time

When the deal was signed for implementing Baglihar after ‘retrieving’ it from NHPC, it was considered almost a scandal. After four cost revisions and five revised dates in 16 years, it is proved once again that ‘change’ is sometimes possible only after going against the wind.

People associated with the exercise said it started with just a dream to jump out of the energy misery. Once it began throwing up challenges, it was an unprecedented learning curve that eventually gave the state it’s most precious project. J&K government that now spends more than Rs 40,000 crore annually, has not any asset as huge as Baglihar is. It also lacks any other project earning more than Rs 1500 crore a year.

Initially it was just a small project but once more than 5000 people started working in the narrow gorge, the requirement for funds surged. With coffers literally empty and no financial organization around to come to rescue, it pushed the project managers into the maze of India’s financial world, to get instant lessons initially and part financial closure later.

Paupers’ Coffer

On Aril 10, 1999 , the state-owned SPDC inked an agreement with Jaiprakash Industries Ltd (JIL) – later re-designated as Jaiprakash Associates on for civil hydro and mechanical works for net basic cost of Rs 1622 crore. On July 17, 1999 another agreement was signed with M/S Siemens (a consortium of Siemens AG Germany and Siemens India Pvt Ltd – now Voith) for the project’s electro mechanical works for US $ 119 millions. To consult and supervise the civil, electrical and electro-mechanical works, the SPDC roped in German consulting agency, the Lahmeyer International in August 1999.

The first payment to the contractor company was Rs 162 crore and of this Rs 100 crore was an overdraft from the J&K Bank. “Then we tried to convince the government that financial closure must precede the start but nobody listened,” one top SPDC officer who was part of the process said. “Argument was simple – wait for the financial closure and that will never happen!”

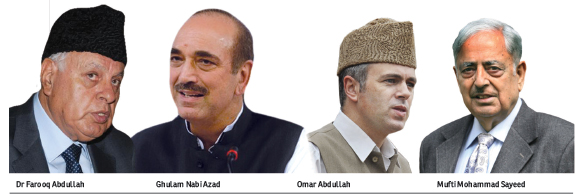

The argument was rooted in not-so-distant history. A year after Dr Farooq Abdullah returned to power in 1996, his government signed an MoU on November 14, 1997 for Baglihar execution on turnkey basis with M/S JPI and M/S SNC Lalivin for technical part. It was part of a series of MoUs, that SPDC signed for five different projects. In certain cases, the consortiums had agreed to even arrange low cost funds against sovereign counter-guarantees.

With an MoU in hand, the government that had replaced a long spell of governor’s rule made its best efforts to get the counter-guarantees but they never came. Hoping against hope, the MoU, lapsed in between, and was resigned in June 1998. Another series of efforts was started to get the counter-guarantees but they never came. For Baglihar, the agreement was finally signed in 1999 and the cabinet decided to implement the project without financial closure.

In the fiscal 2000-01, two payments were to be made and in both the cases loan from the state-owned J&K Bank constituted the main portion of the pyments.

The initial plan anticipated completion of project on December 31, 2004 for which the work was to start on January 1, 2000. But the land acquisition took more time than anticipated. It slowed down the process necessitating revising the work plan strategy. While acquiring the land, the state government adequately used this time to understanding that such a huge project cannot be set up with paltry equity. It needed long term debt!

Bonded Bounty

Raising money from market is a professional job. The first hunt was for ‘money arrangers’, again a first experience. Khandelwal Jain Management Corporation – KJMC was the first company that was roped in May 1999.

Soon after being appointed, the money arrangers and the SPDC officials approached Industrial Development Bank of India (IDBI) and a number of other banks. IDBI showed an interest and appointed Tata Consulting Engineers as appraisers. As they reviewed the project, these engineers said the project cost was high. For any association with IDBI, they suggested change of contract offers and in fact their modifications to suit IDBI requirements and most importantly a power purchase agreement (PPA). No financial institution would lend to a project that has not entered into an agreement in anticipation about who the power will purchase and at what cost.

“We flew here, there and everywhere,” remembers one senior officer. “We visited the Vidyut Boards in Rajasthan, Haryana, and Delhi besides Northern Railways and it was not an illustrious exercise.”

Some electricity boards showed willingness to enter into PPA but put conditions that stopped short of ridiculing the SPDC. Haryana, for instance, sought a 1.5% rebate on the power bill for signing a PPA for Baglihar. The State government had already signed PPA with J&K’s power distributing Power Development Department for half of the power generation.

By then, other money arrangers AK Capitals Services Ltd Delhi, Centurion Finance Ltd Delhi, SBI Capital Market Mumbai had joined the race. As KJMC failed to manage the financial closure, it suggested raising short term bonds.

As the first series of bonds was unrated, the investors required rating of the borrowers and appointment legal consultants. Then, the rating agency Duff and Phelps was hired and Crawford Bailey was engaged as legal consultants for the entire bond series.

These secured, redeemable and medium-term bonds guaranteed for interest and principal payments by the state government were offered on private replacement basis. Even then, its takeoff proved slightly difficult.

In fact, the first series of bonds that closed by January 20, 2000 had 28 investors involved. But the SPDC (read J&K government) could raise only Rs 191.20 crore which fell shot by Rs 70 crore of the requirements of Rs 260 crore: Rs 162.24 crore to be due to the JP and another Rs 79 crore to EMC contractor besides surging demand on the land acquisition front. The way-out found was yet another temporary OD from J&K Bank “against the plan allocations of the SPDC for 2000-01”.

“We raised a total of Rs 1053.96 crore in five tranches from the market,” a senior SPDC official said. “Up to January 2005, we managed running the project work with this money.” It cost the state a whopping sum of Rs 757 crore of interest!

Every time the bonds were issued, the government would issue a formal guarantee and in the third bond series the SPDC mortgaged its “present and future assets”, besides opening two Escrow accounts for future recievables to assure the investors. All these bonds had a green shoe (put and call) option and the money arrangers helped oversubscribe them.

All the bonds are paid back. State government has taken over the liabilities on account of bonds by issuing a formal order on July 23, 2004 and converted it into its equity. But it reneged from its commitment creating a situation that almost Rs 670 crore was paid by the SPDC from its own resources.

Pushed Into Sin

Bonds are instruments used as bridge loans to manage emerging contingencies. The project still required financial closure which was till then elusive.

Unable to convince the FIs to lend, the SPDC was getting lured by off shore offers. It sent a delegation in late 2000 to the ECB division in the Finance Ministry seeking permission to raise US $ 100 million at an interest rate of 6%. It was a follow up to the American Certified Funding Corporation’s offer to arrange Euro Currency Bond that was earlier availed by PFC, NHPC and NTPC. The delegation, however, met with no success.

Prior to that SPDC wanted Deferred Payment Guarantee (DPG) from the central government to access low cost funds from Deutche Bank, Credit Lyonnais and ING BHF Bank. It had failed there as well.

Back home, Dr Farooq Abdullah, the then Chief Minister, had a series of meeting with the honchos of major financial institutions, especially with the IDBI chief. It started working and responses started coming.

IDBI finally sought a plethora of documents for re-appraising the project. The lender believed the project lacked techno-economic feasibility. It took its own time and finally the first letter of intent that SPDC received was in December 2001.

But the pre-conditions that IDBI, and many others who intended to be part of the project, shocked almost everybody. The FI wanted “direct and irrevocable charge on the central plan allocations to the state government”. It wanted first charge on SPDCs all bank accounts including the Trust and Retention Account (TRA) wherein all cash flows would be deposited and the proceeds would be utilized in a manner and priority to be decided by IDBI. It also wanted appointment of the trustees for operating theTRA, pledging 100% equity shares held by the promoters (state government) in SPDC with voting rights and blank transfer deeds, appointing Lender’s Engineers at SPDC’s cost, power to review all tenders, assignments and an assurance that the changes suggested by IDBI would be affected and a right to appoint its whole time director in SPDC.

In addition, IDBI suggested amending state’s harsh Transfer of Property Act. Ceiling its exposure to the project to a level, IDBI said the state government would have to arrange any additional amount from other sources if there was any cost escalation. It offered funding at 3.5% above the medium term lending rate (MTRL), then 12.5%. Besides, it wanted modifications in various agreements with EMC and enter into a wrap agreement with JIL which would constitute single point responsibility for project completion with adequate provisions for liquidated damage to cost overruns. IDBI also wanted J&K government not to take up any other project till the Baglihar completes!

Similar conditions were set by others. After the Board of Directors at SPDC absorbed the shock, it authorized its MD to approach the prospective lender again and seek concessions in the pre-conditions. In a bid to prove the harshness of the conditions being set for the loan, SPDC carried a detailed letter from RBI issued on February 2, 2002 that rejected the idea of these conditions saying this will be a contingent liability on the Government of India.

Dr Abdullah flew to Delhi and met the Finance Minister in July 2002, and as a result IDBI issued a mildly changed letter of intent which reduced rate of interest by a mere 1% but insisted on creating a lien on the Consolidated Fund by retaining the “direct and irrevocable first charge on the central plan assistance.” On these conditions IDBI and HUDCO committed Rs 300 crore each, SBI Rs 250 crore, and Canara Bank, PNB and Central Bank of India Rs 25 crore each – all totaling Rs 925 crore. Power Finance Corporation (PFC) separately committed an exposure of Rs 615 crore.

J&K government made a last ditch effort to get the conditions relaxed and failed again. It had invested more than Rs 1240 crore in the project and had immediate requirement for another Rs 860 crore- a literal devil and the deep sea situation. The rating agency had downgraded its rating for the third series of bonds because of some minor flaw while managing the second, making funds costlier. By February 25, 2000 the SPDC Board t had mandated its MD to “mortgage the assets of Upper Sindh Hydel Power Project and also create the charge on the assets of Gas Turbine plus sale proceeds of 750 million units generation by SPDC” to ensure the next series of bonds does not fail. In such a distressing situation, J&K had no option but to incorporate all these conditions on August 28, 2002.

Planners in the government were happy that money was coming finally. It only required preparation of documents and the devolutions would start. By the time documents were ready for signatures, model code of conduct was in place. And then, a new government assumed office in Srinagar.

At the peak of this ecstasy landed a letter from the central government’s banking division on January 14, 2003. “While the state government had taken adequate steps to create all necessary security acceptable to lenders, conditions which allow the lenders to debit the Consolidated Fund of the state is unacceptable,” the letter communicated. Delhi did not want creation of a precedence that would make financial institutions dictate to the State itself. The entire process was stalled. “Union government’s department of expenditure had permitted the process but now (with this letter) we were back to square one,” admitted an SPDC insider.

Fiscal Rescue

Even the new government led by Mufti Mohammad Sayeed was scared. “If we abandon the project we lose Rs 1400 crore that we have invested,” Mufti publicly said in December 2002, soon after taking over, insisting Baglihar was on the brink of closure. SPDC had already received a slowdown notice from the contractor. “If we have to proceed ahead, we need lot more money.”

Mufti’s cabinet had rejected the IDBI conditions. “The conditions were so stringent and unacceptable,” explained Muzaffar Hussain Beig, the then Finance Minister. “For creating a lien on the Consolidated Fund (that includes the salary of the governor) the constitution needs to be amended which is not possible. We could not have destroy the whole state for one project.”

With Dr Haseeb Drabu, the then Economic Adviser accompanying, Mufti and Beig flew to Delhi with suggestions of possibilities for completing the project “caught in a vicious circle”. They wanted tax free bonds to fund the project if FIs were not interested in it.

Initially, the J&K government was told by the Atal Behari Vajpayee dispensation that Baglihar is being discussed with the Asian Development Bank. Later in the last week of July 2003, Srinagar hosted a conclave of Indian Banking Association (IBA) wherein 19 CMDs of various banks with Dalbir Singh, then Canara Bank CMD as their leader, participated. “This is investment in peace,” Mufti, referring to the Baghliar project, told them in a 90-minute meeting at picturesque Dachigam. Later they announced advancing Rs 1000 crore to Baglihar on easy terms. In immediate follow up, IL&FS was roped in to coordinate them all. By then, SPDC had booked an expenditure of Rs 1600 crore.

The situation started changing rapidly thereafter. By October 2003, Dr Drabu managed convincing the Prime Minister that a special assistance of Rs 630 crore as part of the Prime Minister’s Reconstruction Plan (PMRP) would salvage the project. The only condition for availing this grant was that its every rupee would be released when the SPDC could garner three rupees from the market. IDBI and HUDCO, which had tried to create history by literally taking a state as a mortgage for a few thousand crore loan, were nowhere around. Then, IBA announced committing Rs 1500 crore to the project.

On December 17, 2003, the Mufti led coalition government managed the passage of an amendment in the J&K Transfer of Property (2nd amendment) Act that offers financial institutions the right to sell mortgaged state land to central PSUs and FIs in case the government defaults on loans. Opposition termed it a conspiracy to dilute state’s special status and demanded the bill to be first sent to a select committee. The ruling coalition, however, refused the same and passed the bill in the din.

This development followed he Power finance corporation (PFC) emerging as leader of a new consortium to fund Baglihar on September 23, 2003. Loans were to be advanced at 10.5% interest and repaid in 40 equal quarterly installments starting from October 2006. On November 5 2000, all the lenders met and two days later, they conveyed their conditions to the state government.

On January 7, 2005 – when India and Pakistan talks on Baglihar failed, SPDC inked an agreement with PFC and finally managed the financial closure of the project. With the project’s revised costs put at Rs 4000 crore, the PFC led 9-member consortium–comprising REC, HUDCO, J&K Bank, Canara Bank, Indian Overseas Bank, Central Bank of India, Union Bank of India, and UCO Bank– agreed to advance Rs 1770 crore. The Rs 1600 Cr investment already made by the SPDC into the project was booked as the owners equity and the rest Rs 630 crore came as grant from the centre. Later, however, Three consortium members – Indian Overseas Bank, Union Bank of India and UCO Bank did not disburse their share of totaling Rs 160 crore forcing the SPDC to enter into a separate agreement with J&K Bank for a bridge loan on revised rates on September 19, 2007.

The consortium accepted that half of the generation would be sold through Power Trading Corporation to repay the loans and Power Purchase Agreement (PPA) was signed on November 29, 2006. It marked the conclusion of six years exercise to manage project’s financial closure.

Back To Begging

The financial closure made on January 7, 2005 was express on one thing that any additional cost beyond Rs 4000 crore would be borne by the SPDC and also that state government shall have to buy power from its own project. The state government thought both the conditions were manageable till another calamity hit project. This time it was the ‘Act of God’. The 2005 floods literally decimated the project. The floods did not just change the time lines ; they resulted in massive cost overruns.

Initial estimate of the destruction suggested that the project would cost Rs 1200 more. For Dr Drabu, who headed the state response, arranging additional resources outside the financial closure was a real tough task. As Congress was ruling the state and the centre, it became easier for him to manage the resources. Central government gave Rs 670 crore as interest free subordinate loan to the state which was deducted from the central devolutions later. Fortunately, the Bankers’ consortium also felt convinced that it must lend more so they gave another Rs 483 crore. Balance Rs 47 crore was managed by the SPDC and the state government from its own sources.

“The project did not conclude at that,” admits a senior SPDC officer. “We estimate the phase-I conclusion at an overall cost of Rs 5827 crore of which Rs 5600 crore is already booked.” It includes nearly Rs 640.36 crore that has been paid as ‘Interest During Construction’. He said the additional expenditure was managed by the state and the SPDC from its own resources.

Interesting part of the story is that of the Rs 5600 crore that the project booked, Rs 2253 crore is the debt, Rs 630 crore was subsidy by the central government, Rs 670 crore is the zero-cost debt from centre and the balance Rs 2047 crore is the equity. Of the equity Rs 1053 crore was the bond money raised by the state and provided to te project as owners capital and Rs 954 crore was pure equity. The state government paid Rs 757 crore as interest on bonds that is not added to the project cost. Baghliar, is thus, a unique project that was created more with debt than with equity.

An Earned Dignity

But the entire pain that SPDC underwent for all these years fetched J&K credibility in the money market. Politics apart, former bosses in the SPDC admit that it was a huge learning experience. “It was a lesson we learnt so hard that now we know how it works,” one top officer said. “The investors have a confidence now because Baglihar-I is operational and making money.”

On August 14, 2012 the then MD SPDC Basharat Ahmad signed an agreement with the J&K Bank in Srinagar and on August 23, he was in Delhi for another agreement – this time with PFC.

For Baglihar-II requiring Rs 3113.19 crore, J&K Bank agreed to lend Rs 500 crore whileas the major portion of the seventy percent debt amounting to Rs 1679.23 crore came from PFC. SPDC managed Rs 934 crore as its equity.

“Unlike Baglihar-I that took six years for financial closure, we inked the deal in record time and with favourable conditions,” Basharat, the then MD SPDC remembers. “Unlike Baglihar-I, it was not a crowd (of financial institutions) around and more importantly no collateral mortgaging was involved.” There were only two conditions: state government guarantee and creating an Escrow account.

The only problem that J&K faced was that it had requested the Prime Minister to grant Baglihar-II a viability gap funding. Former Chief Minister Omar Abdullah had written a letter as early as September 2011 seeking Rs 1000 crore support which would reduce the debt burden and improve the project viability. Thought it did not happen but it did not impact the project completion.

Interestingly, there were no defaults in repayment on Baglihar-I which will be debt free by 2019. The second phase will be debt free by 2026.

On repayments front, there is a slight difference between the two phases of the project. Half of generation from Baglihar-I goes to PTC for debt repayment (at a uniform tariff of Rs 3.65 per unit) and in Baglihar-II 60 percent of generations will be sold to PTC for debt servicing. But SPDC insiders say the Power Development Department will have to pay for every single unit that it purchases.