As hundreds of workers were busy burrowing tunnels and laying tons of concrete in the Baglihar gorge, diplomats and water experts from Delhi and Islamabad were fighting a war of nerves overseas. Masood Hussain details the tense days and nights of a ‘trial’ after Pakistan invoked her rights under Indus Waters Treaty, petitioned World Bank resulting in appointment of a Neutral Expert who settled the “difference” over the design of J&K’s new temple of growth

For two complete days in February 2003, the Permanent Indus Commissions of India and Pakistan discussed Baglihar and failed to reach a consensus. In Srinagar a government that had made expensive market burrowings and invested in the dam was so panicked that it asked Delhi to turn down an impending visit of Pakistani Commission officials to Baglihar!

Then, both the countries decided to talk again. They met for four days (January 4-7, 2005) and discussed six ‘contentious’ technical issues. Probably for the first time, they shared the data formally. Islamabad insisted the design violated the water sharing Indus Water Treaty. Delhi disagreed. With slightly less half of the civil works through, Islamabad offered an alternative design which, if implemented, would have left the project without a dam and slashed its output to 137 MWs. Failure of this meeting led Pakistan to petition the World Bank.

For the resource-deficient government in Srinagar that continued lifting loans to manage the project and get out of the ‘energy misery’, the failure of talks added to the tensions. Mufti Sayeed, the then Chief Minister said the project was “Kashmir’s jugular vein”, a “flagship of its future prosperity” and will not be abandoned.

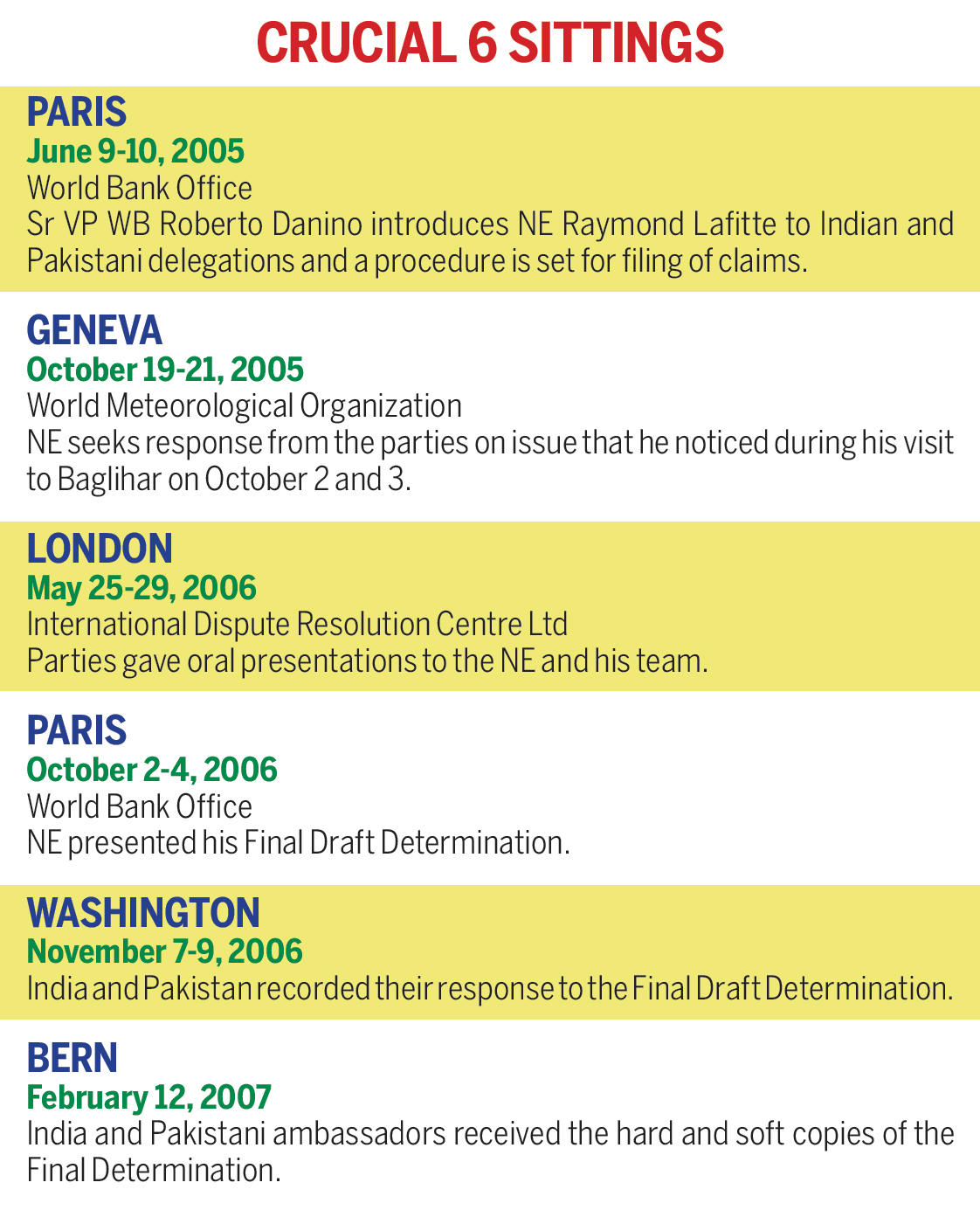

By January 15, 2005 Islamabad had sent a request to the World Bank seeking appointment of a Neutral Expert (NE). Raymond Lafitte, Professor at the Federal Institute of Technology of Lausanne, Switzerland was appointed as the NE on May 12, 2005, the maiden third party intervention under Indus Water Treaty.

Signed on September 19, 1960, the Treaty was brokered by World Bank. It was in fact outcome of the Bank’s efforts to help two nations manage their water resources. Australia, Canada, Germany, New Zealand. Britain and the US were part of collateral Indus Water Basin Development Fund Agreement. The Treaty that survived all the wars between the two countries has a set mechanism of engagement and crisis-management.

The two sovereign states can settle a ‘question’ – the basic disagreement on issues arising out of engagement, bilaterally, the Treaty rules. If they fail, the ‘question’ becomes a ‘difference’ that can be settled by an NE which only WB can appoint while keeping both the parties in loop. If it is more serious, the Treaty terms it a ‘dispute’ which can be tackled by a court of arbitration whose head is appointed by the UN Secretary General.

Pakistan went to the NE with three ‘differences’. Firstly, the design of the project was not based on “correct, rational and realistic estimates of maximum flood discharge”. Secondly, the pondage of 37.722 million cubic meters (in the dam) exceeds twice the pondage required for Firm Power. And finally, intake for the turbines was not located at the highest level consistent with satisfactory and economical construction and operation of a run of the river plant. Pakistan termed all the three differences as violations of various provisions listed in Treaty’s Annexure D. Delhi held a contrarian view on all.

“New Delhi believes the dispute has little to do with water, and is primarily a political issue raised by Islamabad to prevent India from completing projects that benefit Kashmiris, as the hydroelectric project is designed to do,” David Mulford, US ambassador in Delhi cabled back home on January 12, 2005 after meeting officials of two countries managing the Baglihar differences. “Looking back historically, the (MEA) Joint Secretary (Arun K Singh) saw the Dam as analogous in some respects to the Wullar Barrage / Tulbul Navigation Project, which the GOI (Government of India) delayed for several months as a favor to Benazir Bhutto, not as a treaty provision. Once the GOI stopped it, he continued, Islamabad “had what it wanted,” and refused to engage substantively after that. India will not make the same mistake again.”

A set of cables, leaked by wikileaks, details the efforts made by Delhi to prevent Islamabad from involving a third party. To counter Pakistan’s argument that India wanted to withhold water and cause flood, Mulford cabled India’s “benign intentions” to the State Department on February 25, 2005 saying “..if its dam were used to inundate Pakistan, one of its own existing downriver projects (Salal) would be the first casualty.”

Delhi even offered certain design changes to Pakistan. Monica Mohta, the then Director MEA (Pakistan) informed Robert O Blake, Malford’s deputy, that prior to President Musharraf’s visit to India, “The GOI had conceded “two-and-a-half” of Islamabad’s six technical objections by agreeing to dispense with low-level intakes for turbines that would have shortened the project’s timeline by eight weeks, and replacing a ‘sluice spillway’ with a ‘shoot (it probably is chute that is pronounced as shoot) spillway’.” This, she told the US diplomat, was reiterated by Prime Minister Dr Manmohan Singh to Musharaf when the latter visited India.

Consistently, Delhi exuded confidence that the project was Treaty-compliant and no expert can prove it wrong. In fact, they had set up a ‘hydraulic model’ of the Baglihar at the Irrigation Research Institute (IRI) in Roorkee. Mulford detailed this model in a July 10, 2005 cable terming it a 1:60 scale “running model” of the dam. “The 200-meter large model is powered by the Ganga Canal and reportedly allows observers to note the water’s behavior as it runs through the sluices, intake points, channels, and reservoirs.” During his 5-day visit to India in October 2005, the NE actually spent two days (October 2-3) at Baglihar and two days (October 5-6) in Roorkee interacting with the Directors of National Institute of Hydrology (NHI) and IRI.

Aware of what had happened to the Navigation Lock at Tulbul, Baglihar owners in Srinagar were keeping their fingers crossed. “We had been assured by the central government that the project will come up at all costs,” remembers Basharat A Dhar, the then Managing Director of the J&K’s State Power Development Corporation (SPDC), now heading the State Electricity and Regulatory Commission (SERC). “But we had the apprehension that the verdict could go either way and that would be disastrous for a state that was literally managing every single penny at huge costs.”

In October 2006, when the NE shared his draft determination with the two countries, tensions went up. Analysis of the draft indicated the verdict may cost heavily, even though the basic design was unchanged.

In October 2006, when the NE shared his draft determination with the two countries, tensions went up. Analysis of the draft indicated the verdict may cost heavily, even though the basic design was unchanged.

In his 116-page Final Determination that was handed over to the ambassadors of the two countries on February 17, 2007, NE discussed every issue in detail. He gave six Determinations.

Maximum design flood was a key basic difference between the two countries. India had evaluated Probable Maximum Flood at 16,500 m3/s (cubic meters per second) and Pakistan calculated it to be 14,900 m3/s. NE adopted the Indian calculation insisting: “Climate change, with the possible associated increase in floods, also encourages a prudent approach.”

Baglihar dam has five main sluice spillways, three chute spillways and an auxiliary spillway located at different crest levels. From day one Islamabad was against any gated spillway. NE, however, ruled that gated spillways are “in conformity with the state of the art” and the conditions at the site of the dam “require a gated spillway”. He stated that gated spillways are “consistent with the provisions of the Treaty”.

The two countries had completely diverse opinions on the level at which gated spillways would operate. Pakistan complained that the proposed orifice spillway was “not located at the highest level consistent with the provisions of the Treaty”. India’s position was that these were necessary to ensure safe passing of the design flood, and also a silt-free environment near the intakes for trouble-free operation.

NE ruled the gated chute spillway on the left wing were “at the highest level consistent with sound and economical design and satisfactory construction and operation of the works.” Considering that the spillways were for “sediment control of the reservoir and evacuation of a large part of the design flood”, NE ruled these should be of the “minimum size and located at the highest level (808 m asl)”. But for ensuring “protection against flood of Pul Doda, the outlets should preferably be located 8 meter lower, at about elevation 800 m asl (meters above sea level).”

“Sound operation of the outlets will necessitate carrying out maintenance of the reservoir with drawdown sluicing each year during the monsoon season,” the NE determined. “The reservoir level should be drawn down to a level of about 818 masl that is to say 17 m below that of the Dead Storage Level.”

Pakistan had issues with dam crest elevation thinking it would be used to raise the pondage level. The dam design suggested a full pondage level of 840 m asl and the total freeboard above the full pondage level of 4.5 meters. NE did not find the freeboard at lowest elevation. “The Determination of the NE is that the freeboard should be of 3 m above the Full Pondage Level leading to a dam crest elevation at 843.0 m asl,” the verdict reads. “This is possible if the design of the chute spillway is optimised by minor shape adjustments in order to increase its capacity.”

One of the main concerns of Pakistan was the pondage of 37.722 MCM (million cubic meters) in the dam, which, she believed exceeded “twice the pondage required for Firm Power” and was violating the provisions of the Treaty. NE insisted that “the values for maximum pondage stipulated by India as well as by Pakistan are not in conformity with the criteria laid down in the Treaty”. He ruled that maximum pondage should stay at 32.56 MCM and the corresponding Dead Storage Level must be an elevation of 836 m asl which is one meter higher than the level of the Indian design.

Another major issue that Islamabad was consistently insisting on was the level of intake from dam to the two stages having three turbines of 150 MW each. Each of the two tunnels, located at an elevation of 818 m asl were draining 430 cubic meters per second (cumecs) of water to run the turbines. NE was dissatisfied with the Indian design and changed it. “..intake level should be raised by 3 m and fixed at el. 821 m asl,” he ruled.

Of the six ‘determinations, three each favoured either of the two parties. For Pakistan, the spillway award was a severe blow. The NE upheld India’s design for maximum flood discharge and both the controversies on spillways. NE upheld Pakistani position on changing the elevation of the power intake channel, reducing the dam freeboard by 1.5 meters and lowering the pondage of the dam.

The NE, however, played a diplomat at the cost of the arbitration insisting that his decision was not rendered against one or the other party. “In principle, costs are to be borne by the unsuccessful party…The logical basis for this policy appears to be that a “successful” claimant has, in effect, been forced to go through the process in order to achieve success, and should not be penalized by having to pay for the process itself. The same logic holds true for a successful respondent, faced with an unmerited claim”, the Lattife report said. “In conclusion, having considered the content of his decision, paragraph 10 of Annexure F which gives him discretion in “special circumstances” and the practice of international tribunals, the NE decides to share the costs equally among the parties”.

The win-win situation of the verdict led Islamabad and Delhi to claim victory. As politicians were hawking the victory, the engineers on site were assessing the impact the verdict woud have on account of changes in power intake. This was considered crucial because experts at Roorkee had suggested the power intake should take off slightly at a lower elevation than designed. Now, NE wanted increase in elevation and the threat was formation of vortices and swirls which could trigger bubbling thus destabilizing the plant.

Installation of anti-vortex devices would require additional investment but the world famous hydrologist Dr Schwartz from Lahmeyer International GmbH, the SPDC consultants for the project, decided to go ahead. Eventually, it worked: No swirls were formed.

One great advantage that SPDC had was that the changes did not require any major dismantling as the work was still in progress and much below the spots where design-changes were ordered.

But tensions continued. In August 2008, a month ahead of the trial runs, Pakistani Commission officials visited the site to see if the changes ruled by the NE were made.

Soon after, when the reservoir filling started, a 7-member Pakistani Indus Commission landed to check it again in October third visit in less than three months. Treaty permits reservoir-filling between June 26 and August 31, a schedule SPDC followed. Islamabad said it was alright but they did not receive a minimum of 55000 cusecs discharge. They threatened to seek compensation as the discharge fall impacted people. However, they returned satisfied that low rainfall was the culprit and not the dam.

Now the project is in operation for almost seven years. Second stage also started generations though it is currently not running for lack of discharge. For the time being, everybody seems to be in ‘aquatic’ peace.