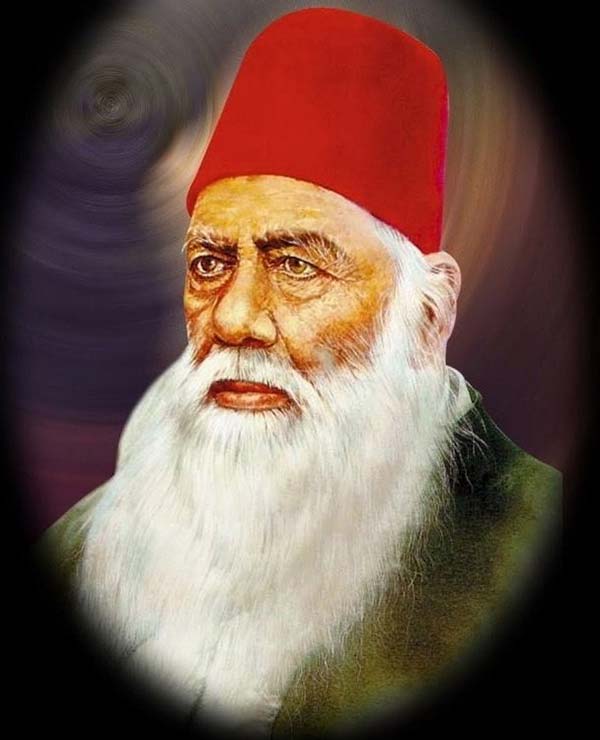

Scholar Nayeem Showkat reviews a brand new biography of AMU founder, in which the author has taken a deep dive into the unexplored history to suggest that Sir Syed Ahmad Khan’s focus areas were to explain why the ‘work of God’ and ‘word of God’ are supplementing each other

Writing a book on Sir Syed Ahmad Khan is an exceptionally daunting task as much has been written, contested and critiqued in scholarly contributions, so far. To have an impact on current scholarship, it entails delving further and venturing into innovative approaches to unveil the unexpressed and rectify the misplaced information surrounding him.

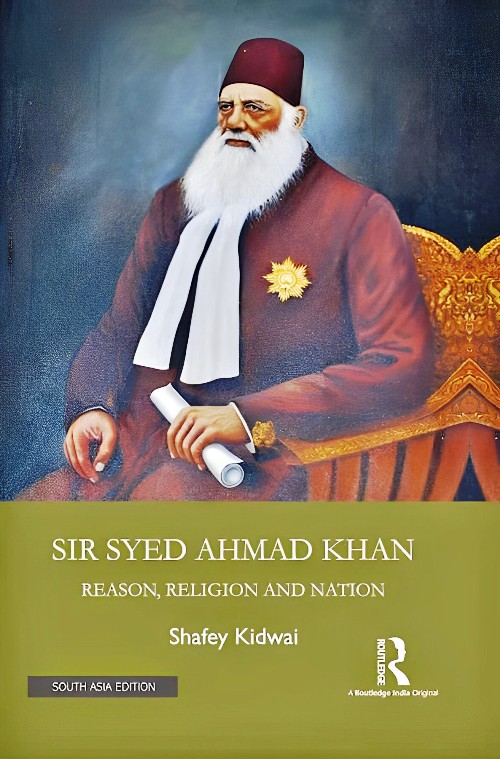

At a time when Aligarh Muslim University (AMU) is celebrating its centenary, the 2019 Sahitya Akademi awardee for Urdu, Professor Shafey Kidwai has come up with the latest biography of the varsity founder Sir Syed Ahmad Khan. The book Sir Syed Ahmad Khan: Reason, Religion and Nation published by Routledge debunks various myths and misreading prevalent about the modern education reformist of India, whose contribution according to Kidwai has been confined to merely being the founder of Aligarh Muslim University.

In the light of reason, the author re-examines various aspects of his life as a religious scholar, journalist, administrator, philosopher, civil servant, reformist, and so on. Kidwai goes on to report several fallacies in the discourses of Graham, Hali and others and asserts that Sir Syed has reckoned reason as the cognitive postulate to understand the elemental truths.

Complementing Science with Faith

Professor lays threadbare his emotion-avoidance-prone outlook, which has attracted criticism and acceptance simultaneously from different quarters of society. He emphasises Sir Syed’s vision of reason as the basis to resolve the conflict between the ‘word of God’ and the ‘work of God’. Sir Syed avers that science and religion are complementary to each other and no dichotomy exists between the two.

Kidwai delineates a detailed biographical narrative of Sir Syed, which offers a fresh perspective on his life while unravelling various unexplored and wrongly attributed facts about him. From his family history to his father’s name, to his mother’s role, to the story of his wife, two sons and daughter and many others, the book corrects many misreported things about the founder of AMU and his kith and kin.

Sir Syed was of the opinion that while violence should be eschewed, rebuttal in the form of writing is the best method to solve critical issues. He believed in religious freedom without any kind of political or official pressure.

Freedom of Expression

Sir Syed overtly supports freedom of expression, with his writings bearing testimony to his extraordinary capability of unequivocally explaining its epistemological framework and empirical dynamics. The writer reveals that Sir Syed was an ardent advocate of free speech even in matters of belief. He held that truth can’t be vanquished, irrespective of its being consonant with the opinion of the majority or otherwise. These ideas resonate closely with Chomsky’s concept of ‘manufacturing consent’, Professor Kidwai observes.

Sir Syed executed the phenomenal task of creating the much-required public sphere to foster the discussion on socio-political issues to influence policy and action. While he is hailed as the man behind shaping the democratic consciousness, the presence of the metaphors of resentment against the direct elections and a few other elements of democracy make Sir Syed’s philosophy somewhat akin to that of Socrates.

The singularity of Kidwai’s book is that it is a very pertinent aberration from the hitherto existing biographies, in that it analyses Sir Syed’s work in the light of significant questions prevalent in nineteenth-century India.

Key Questions

The questions of gender equality, modern education, women’s education, British imperialism, conversion, democracy, politics, scientific temperament, development, cultural supremacy, and Urdu-Hindi controversy have been thoroughly discussed and critiqued. Apropos the shifting dynamics of the meanings of watan and qaum as reflected in Sir Syed’s writings, Professor Shafey Kidwai’s discourse is an indispensable resource to comprehend the AMU founder’s standpoint.

One exemplary contribution of Sir Syed, among many others, that is overlooked was his contribution to convincing the British government of the exigency of the public-friendly railway service in India. He is a proponent of both male and female education in definable steps as he opines that “cultivation of female should be indirect, aiming first at the reformation of the men who when they have arrived at a particular stage of progress will raise the women to their level.” Considering the level of ignorance and dogmas in society at that time, he observed that the empowerment of women may further perpetuate an imbalance in society as the males were not ready for such empowered women.

Sir Syed rather proposed an alternative and indigenous model of education, which focused on home-based teaching for women initially. Another fact brought to light is that while earlier Muslim travellers to Europe had only focused on European women regarding their promiscuity and lascivious behaviour, Sir Syed, on the contrary, showered heaps of praise on those women with respect for their educational achievement and empowerment.

Cultural Supremacy?

Demolishing the idea of cultural supremacy, Sir Syed avers that no culture is infallible, since every culture carries some unique features and is simultaneously deeply mired in human feelings and defects. His viewpoints were in line with the twentieth-century works of Franz Boas and his students, with roots in the writings of Johann von Herder.

The author posits that Sir Syed overtly endorsed patriotism as is evident from all his writings. Indeed, he describes patriotism as a significant manifestation of love, in the light of his interpretation of the religious texts.

Stating that bias should be avoided at any cost, he stressed the need for balanced views in writing, particularly history. Regarding the essence of journalism, Sir Syed emphasised the significance of both information and enlightenment, in that he believed that it was incumbent upon the newspaper to not only provide information but also to supplement the readers with insight about relevant issues.

Scientific Society

Setting up a Scientific Society way back in 1864, Sir Syed can be termed as one of the first to realise the importance of instilling scientific temperament in the Indian youth. A strong indicator of his acute scientific temper is that the largest share of publications in his Aligarh Institute Gazette pertains to scientific discoveries and innovations.

The observations lay out in the framework of the content analysis show that religion was the least preferred subject in Sir Syed’s newspapers. His journalistic endeavours remain considerably important in the realm, as he can conveniently be said to have pioneered ‘public service journalism’ in India, besides laying the foundation of development journalism in Urdu.

Sir Syed had a multi-faceted personality, as is discernible from his penchant for wordplay. He contributed a copious number of articles in his periodicals, employing techniques of ‘persuasive prose’ filled with nuances of humour.

The book erects a new image of Sir Syed in the reader’s mind, however, it leaves one wondering if it was Cambridge that made a more significant impression on Sir Syed, why AMU is not dubbed as the Cambridge of the East, but Oxford. Professor Kidwai treads the ‘road not taken’ when he decides to deviate from the oft-repeated practice of simply eulogising Sir Syed’s accomplishments and rather adopts a lens of reason to evaluate the bent of the reason that is ubiquitous in writings of the latter, augmenting its scientific validity, thereupon.