At a time when efforts are underway to request the search giant Google to add Kashmiri to its translation services, Khalid Bashir Gura met a number of young men who are creating content in Kashmiri in order to help the mother tongue survive in tune with the trends that new technologies and the media are dictating

When Touqeer Ashraf, 22, a resident of Pulwama, came to Srinagar for higher education at the university level, he felt bothered at the treatment his mother tongue met especially in the social sphere. He felt, that people were ashamed or battled an inferiority complex while speaking in their mother tongue. Even elders, he said, discouraged kids from speaking.

This led him to think about the “crisis” and he wondered about how to promote and preserve the language which is essential to one’s identity. Now, Touqeer belongs to a generation of young men and women who are taking the language to millions of people using social media.

The Virtual World

Spoken by more than seven million people in Jammu and Kashmir, according to the 2011 census, like him, a handful of language enthusiasts are using social media to rekindle the love, and essence of language and draw the younger generation towards Kashmiri language and culture. This helps the new generation to rediscover their roots, reconnect with their culture and, in a way, reclaim their status.

At their yearly conference, Adbi Markaz Kamraz, Kashmir’s frontline cultural organisation announced that they are approaching Google, to request the search giant, to add the Kashmiri language to its translation services. They have already made a beginning by sending emails. The service once rolled out will help users to convert any content into Kashmiri and vice versa.

“They may do it on their own someday but our campaign is aimed at creating urgency so that we do not lose more time,” a functionary of the Markaz said. “There are smaller languages which have the translation facility and we are slightly a bigger one.”

Once this happens, tons of content in audio-visual or text format will get a service and make the content global in a single click. That is expected to be a game-changer as non-natives can read, watch and listen to Kashmiri in their own language. This will help the new generation have a global audience.

A New Generation

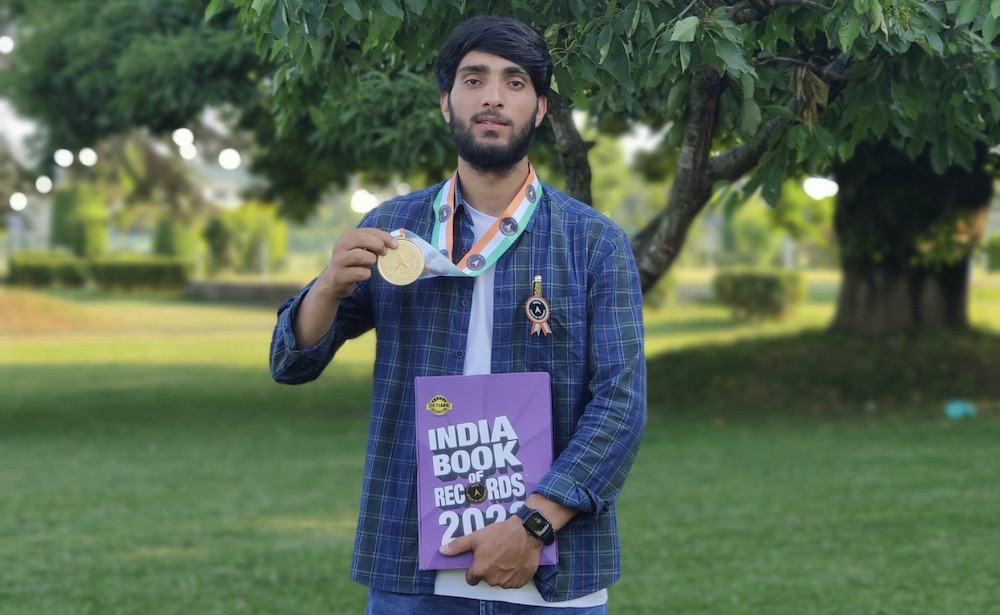

Even though Touqeer has not formally learned Kashmiri at any institution, he has studied Kashmiri till the eighth standard. “My love for my mother tongue never diminished,” he said. “I kept reading language luminaries. But their wisdom and words were not accessible to common people as everyone cannot read and write Kashmir.” That is why, he said, he thought of harnessing the power of social media.

Touqeer started reading the works of the pioneers of Kashmiri literature and later uploaded their work selectively on his social media platforms, under the social media handle KeashurPraw.

“Initially I was apprehensive about the response but as content was appreciated and acknowledged, I felt the urge to work more. I also translate to make it comprehensible to those who do not understand it,” he said.

Laced with the poetry of Kashmir’s fourteenth-century Sufi mystic, Sheikh Nooruddin Noorani, stalwarts of Kashmiri literature and mysticism like Mahmood Gami, Rasul Mir, Lal Ded and Mehjoor, in 2021, he started his YouTube channel. Overlaid with his voice, some background music and pictures and places, he started uploading short videos, reels which soon became viral and garnered him lakhs of followers on other social media platforms.

By now, his collective viewership of all his videos has crossed thirty lakh views on YouTube. On Instagram, KeashurPraw has more than 100 thousand subscribers. “The response is extremely good,” he said. “Kashmiris based outside India and even non-Kashmiris reach out to me and encourage me to do more.”

Since the Kashmiri language has been influenced by other languages and has accommodated hundreds of non-Kashmiri words, Tauqeer lays emphasis on, promoting the “purer” form of Kashmiri to the new generation. Apart from research and uploading, his focus on pronunciation is vital.

It is not just the language which influenced him to promote it but the rich Kashmiri literature has been alluring. The present education system and societal perception of language are responsible for the deteriorating status of language, he believes. That is key to his efforts and the interventions.

A Teacher’s Initiative

Unlike Touqeer, Afaq Ahmad Paddar, a resident of Qazigund, is a postgraduate in the Kashmiri language and has qualified SET examination. He is teaching in a private school in his village. He also started promoting Kashmiri language through social media platforms @sozkmr where he uploads audio poems of different Kashmiri renowned poets.

Personally, he also writes poetry in his mother tongue. He provides rich descriptions of the poems and poets at the time of uploading audio-visual content. However, he does not translate the Kashmiri poetry like other content makers which makes it difficult to comprehend the verses.

After completing master’s, he could not get a job as Kashmiri lacks employment opportunities in the government sector. Later, he switched to English literature. “Now, I am now teaching both languages in a private school,” he said.

His failure to get a job on the basis of his mother tongue skills did not diminish his love for poetry as he continued to write and was acknowledged by his peers and teachers. “I am more inspired by the poetry of Rehman Rahi, Aga Shahid Ali, and Amin Kamil,” he said. “The social media audiences’ especially the young generation love listening to Kashmiri poetry on social media despite limitations of not being able to read or write.” As his social media followers are not many, but it has not de-motivated or prevented him from contributing towards the popularisation of his mother tongue. He does it every time he has the spare time.

Visual Archive

During Covid19, the verses of Sheikh Nooruddin Noorani, on the wall calendar of a Masjid caught the attention of Muneer Ahmad Dar, a resident of Budgam. He recalls his struggle to give voice to his thoughts in his mother tongue.

A postgraduate in economics and mass communication, he had acquired some experience working in the field of media. It was within the praying space of the mosque that he got an idea about translating these rich verses and uploading them on social media to help them reach a wider audience. The ideation of the project coming within the four walls of the mosque gave it some sanctity in his own mind.

“Earlier I had bought the book of Sheikh Nooruddin Noorani but I used to read the translation part of it as I could not comprehend pure Kashmiri, Muneer admitted. “I would photograph the verses, and their translations and WhatsApp to Kashmiri language researchers in the University to learn more.” Soon, he started forwarding the same to people on social media who reciprocated enthusiastically to the verses full of wisdom.

During Covid19, when everyone was confined to homes, he harnessed the true power of social media. “I was stunned by the response. The videos garnered millions of views and it encouraged us to come up with more creative, diverse content,” he said.

His content is in “pure” Kashmiri and aims to shed light on the traditional and cultural objects of Kashmir – from the rich variety of furnishings used in Kashmir in the past or the origins of certain Kashmiri idioms to old heritage houses, life style to information about people and places.

To have a glimpse of the past, Muneer said he wants to build a visual archive of Kashmir’s traditional culture for the future generations and terms it as his legacy.

Muneer’s Facebook page Muneer Speaks has more than 3.50 lakh followers. On YouTube, his content goes under the banner of a channel, @MuneerSpeaks “Mr Koshur”, which has more than 43 thousand followers.

“We uploaded content where we compared our past with the present-day life,” Muneer said, insisting his work involves a lot of research. He admitted the larger reality that people have stopped, by and large, to study and they use audio-visual content to consume knowledge. “Not many people read books now,” he said.

“It is the passion which keeps us going. Our Rate per Minute (RPM) is very low because of geographical and language limitations and whatever money we earn, is not enough for the projects,” he said. Despite this monetary loss, he said he did not want to switch language as it is the USP of his content creation.

His single video according to him, takes at least a week’s time to brainstorm an idea, research correct information, scripting, shooting and editing, and uploading he said.

To give a global touch to his videos, he ensures subtitling in other languages so that non-natives can also understand the content better. “This is not my business or source of my survival he said, but passion,” he said.

Muneer’s focus on cultural aspects of Kashmir in his native language has won him fans from across the globe. One section which has ardently praised his work is the Kashmiri diaspora which views his videos as a way medium to stay connected to roots.

His team compromises of his wife and a researcher who digs details from different sources for his videos.

Online Tutor and Novelist

The online supporters of the Kashmiri language are not content creators alone. It is a huge basket of people, who deliver different services for the popularisation of the language or making its foundations strong on the internet, the virtual world.

Asif Tariq Bhat, 25, a recent postgraduate in Kashmiri language is teaching his fifteenth batch of students in online mode from different parts of the world. Most of them are not Kashmiri but are interested in pursuing the language for different reasons.

“Not all of my students have Kashmir origins,” Asif said. “I have an offshore student who is marrying here and she is also learning the language. There are tourists who do not want to be fleeced while travelling in Kashmir. Similarly, there are researchers, travellers, journalists, who learn Kashmiri for their own individual reasons.”

Similarly, there are families who have Kashmiri origins and want the new generation to learn their mother tongue to stay connected to their roots. There are people in his class who wish to remain anonymous while learning but learn language.

“I charge Rs 5000 for teaching reading and writing Kashmiri. If someone is interested in speaking only, I charge Rs 3000 for four classes a week,” he said.

Besides his teaching, at a time when Kashmiris are experiencing linguistic handicaps in reading and writing their own mother tongue, Asif has written a novel in the Kashmiri language. As is the trend, the youth usually self-publish in other languages to taste fame with no contribution to any language or literature.

He published his first novel in July 2022 after a lot of struggle as every publisher turned him down. The publishers he approached told him they do not publish Kashmiri books as nobody is interested in reading them. These experiences were the signs of the status of language in society.

“I wrote my synopsis for the Kashmiri language novel Khwaban Khayalan Manz, in English. One publisher agreed to publish after learning that the draft was praised by illustrious writers of the Kashmiri language,” he said.

Asif struggled to find a novel in the Kashmir language. The abundance of literature in other languages in the market hurt him. “I was surprised to learn that we are mostly taught the translation of other global writers,” he regretted, questioning why students of the language cannot be taught the Kashmiri literature itself.

Now, Asif has decided to take his novel to a wider audience in a different form. “I am in talks with some social media platforms where I can publish an audiobook of my novel so that Kashmiris who are unable to read the script, can grasp it,” Asif said. “I feel if you listen to something in your native language, it seeps into your heart,” Asif said the youth who are promoting language on social media platforms are doing a wonderful job. “But they should not complicate the language,” he suggested. “The language survives as long as it adapts and updates itself. They must know that the Kashmiri language has survived Sanskrit, Persian, Urdu and now English influence. It is still here.” He disagrees with certain linguistic crusaders that they cannot retain the purity of the language.

Teacher

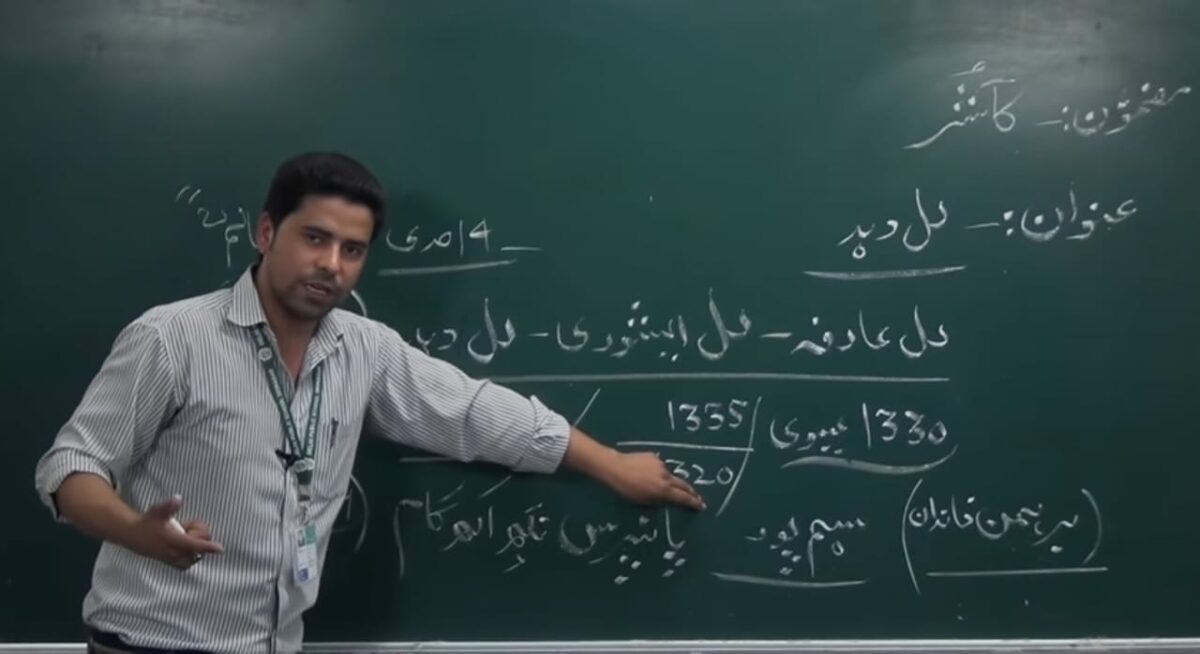

According to Sajid Reshi, who teaches in one of the leading private schools, language should be caught not taught. He has a YouTube channel, @paninzyavpaninkath as he enjoys thousands of subscribers which he has dedicated to learning and promoting Kashmiri language, script, literature, folk stories, Kashmiri history and culture.

“Kashmiri content lacks digital presence,” Reshi regrets. “I am trying to take it to that space. Also, through digital storytelling, it caters to wider audiences including the Kashmiri diaspora.” He gets demands from parents to create content. He appreciates those who do not have a language background but are passionately promoting the language but are disillusioned with organisations that claim to be its guardians.

Pertinent to mention that, the National Education Policy 2020 advocates that “wherever possible, the medium of education will be the mother tongue, local language, regional language until at least Grade 5, but preferably until Grade 8 and beyond”, both in public and private schools.

The essence of language is also essential for communication. “If someone becomes a doctor but does not know the language of common folks, how can he connect with the patient? Irrespective of the profession one aspires to find oneself in, language is the medium to connect,” Reshi stressed.

Kashmiri Dictionary

When Asiya Hassan, a graphic designer, confronted the challenge of teaching Kashmiri to her nephew, she searched the internet. She felt a lack of online resources to teach the language. The idea of setting up the page, Kashmiri Dictionary on social media came out of the lack of online resources about our language.

Kashmiri language expert, Prof Shad Ramzan said the academia must encourage the digital conversion of the Kashmiri literature but he had a rider. “For years, a very well respected group of researchers at the Jammu and Kashmir Academy of Art, Culture and Languages worked on Kashmir dictionary and it is complete,” Shad said. “People who wish to use the Kashmir dictionary must use this only and not add to the confusion.”

Charity Begins at Home

The Kashmiri language is not endangered as long as people speak it. Dr Nazar Ali, who heads the Kashmiri department at the Central University of Kashmir said the private schools also do not encourage students to speak in their mother tongue. “We need to assess who teaches Kashmiri at a basic level as in many schools the situation seems to be serious,” he said. “Have schools recruited expert teachers like other subjects specifically for teaching this language?”

As we teach at the post-graduation level, many students have weak comprehension of their own language.

“Even if I speak in Kashmiri at home with kids in Kashmiri, we feel left out of race,” he said as the initiative to learn and promote language should be started at home.