Jammu Kashmir history’s most financially empowered Panchayat, elected in a challenging situation in 2018 amid boycott and threats, is completing its term in early 2024. Apparently apolitical, they performed as per the capacities they had and the flexibility the governance structure permitted. As the new election is delayed, the crucial grassroots set-up may have to wait for a long time till the new faces emerge in an election that will be hugely contested, reports Syed Shadab Ali Gillani

Panchayats, the major chunk of elected representatives at the grassroots level are completing their term on January 9, 2024. By the end of 2023, almost all elected bodies linked to the developmental activities will complete their terms.

Now their authority will be exercised by the bureaucracy. With the assembly in deep freeze, since 2018, Jammu and Kashmir will now again be completely under the control of the officials, and political parties have consistently been crying around.

In Jammu and Kashmir’s intricate landscape, the Panchayats have remained the main hotbed of politics. It remained choked in the power struggle within the political class till Omar Abdullah’s government retrieved it from a morass after 33 years. The institution literally bled in the subsequent years.

Even the last election, held in 2018, was marked by political standoffs, militant threats, and unexpected contenders. Still, 74 per cent of voters turned out. In the subsequent years, it became the major success for the successive gubernatorial regimes.

“The five-year tenure of almost 40,000 panchs and sarpanchs is going to end on January 9, 2023. Now we are requesting the government to announce panchayat elections as soon as possible so that we have somebody to represent the people of Jammu and Kashmir,” Anil Sharma, who heads the All Jammu and Kashmir Panchayat Conference, said. “There are more than 4192 panchayats in Jammu and Kashmir, who will represent them? After the assembly was dissolved, we have nobody but these panchs and sarpanchs to represent it.” Some of his colleagues think that the Manoj Sinha government may consider “extending the term”.

Amid these demands, the questions being asked are: How did the last elected PRI members function? What was the impact on the ground? And, how it is going to impact the politics in near future?

Driving Grassroots Development

Junaid Ahmed, a 24-year-old Sarpanch hailing from the Chandhara area of Pampore, emphasises the substantial progress achieved in his constituency since his independent candidacy triumph in 2020.

“From digging two bore wells servicing around 800 households to completing the macadamisation of a major road pending for four decades, and the construction of a four-story school building — the list goes on,” Junaid said. “Resolving the long-standing electricity issue, a transformer was installed.”

Despite overtures from political heavyweights, Junaid remains resolute in his independence, driven solely by a commitment to the welfare of his constituents. “There are ample funds if one is sincere and knows how to utilise them for the people’s benefit,” he insists, a sentiment echoed by the villagers who now proudly attest to the positive change in their lives.

Sheeraz Ahmed, a resident, extols Junaid’s tireless dedication, particularly in navigating the challenges of winter when snow-clogged roads threaten accessibility. “He spares no effort in promptly deploying snow-clearing machines, a testament to his unwavering dedication,” applauds Ahmed.

A resident, unwilling to speak on the record, draws a comparison with the previous Sarpanch affiliated with the PDP, and lauds Junaid’s efficiency and reliability, pointing to a marked improvement in governance.

Direct Funds

Since 2010, a senior officer in the Jammu and Kashmir government said the Panchayat are emerging major developmental modules which have access to a lot of funds. “The funds are directly proportional to two things – one the households living in a Panchayat and the vibrancy of the elected body in a particular panchayat,” the officer, speaking anonymously said. “By an average, a Panchayat gets one crore rupees a year but there are Panchayat which have been spending upward of Rs 3.5 crore as well.”

“If you go deep inside the villages, you will see the face of the villages changed,” the officer said. “In Kashmir, we were supposed to create one lakh man-days under MGNREGA till October, we have created 1.70 lakh and it is still going on.”

The officer said at the ground level they are facing two major issues- one, the elected women do not exercise their authority and, two, the elected members are unaware of their rights and powers. “They have a role in almost every department. There is no possibility of a payment being made by us unless the Panchayat signs it and there is no possibility of approving a project if it has not formally come from the Panchayat.”

Delving into the financial landscape, activist and writer, Dr Raja Muzaffar Bhat, highlights the positive evolution. In times past, acquiring funds for essentials involved persistent lobbying with the Member Legislative Assembly (MLA). However, Dr Bhat notes a paradigm shift, stating, “Panchayats now receive substantial funds in various forms, enabling them to enhance village infrastructure.”

With direct grants to Panchayat Institutions amounting to approximately Rs 23.5 lakhs, coupled with contributions from the 16th Finance Commission and MG-NREGA, the financial injection is substantial. Additional funding streams, including the Prime Minister’s Rural Housing Scheme and Swachh Bharat Mission Grameen, further fortify the Panchayats‘ financial arsenal.

Panchayats are now spearheading initiatives such as purchasing transformers using PRI Grants. The proactive involvement of DDC Members and BDC Chairpersons in funding power transformers, once reliant on individual efforts or MLA interventions, underscores the newfound efficacy of local governance. “Residents in many small Panchayat villages have pooled resources to address electricity issues, showcasing Panchayats’ active role in meeting local needs,” Bhat said.

Evolution of PRI

In Jammu and Kashmir, the Panchayat system was introduced by Maharaja Hari Singh in 1935, but it was mainly used for judicial and civil administration. Post-partition, the Panchayat system was amended by Sheikh Abdullah. The Panchayats were nominated by the government and had limited powers and functions.

In 1989, the Jammu and Kashmir Panchayati Raj Act was enacted, which provided for a three-tier system of Panchayats, like the rest of India. However, the act was not implemented fully, and the Panchayat elections were held irregularly and incompletely. The Panchayats also faced threats and attacks from militants, who opposed their participation in the democratic process. The Panchayats also demanded the implementation of the 73rd amendment in the state, which was not done due to the special status of Jammu and Kashmir under Article 370.

After the abrogation of Article 370 in 2019, the central government amended the Jammu and Kashmir Panchayati Raj Act and introduced the ‘extra-constitutional’ fourth tier of Panchayati Raj, namely the District Development Councils (DDCs). The DDCs are directly elected by the people and have the powers and functions of the district planning and development boards. The DDC elections were held in 2020.

In 2000, Jammu and Kashmir witnessed its inaugural Panchayat election under the JK Panchayati Raj Act of 1989. Following the conclusion of Panchayat’s term in 2005, the state grappled with a six-year hiatus in holding elections. It was not until 2011 that the region saw the fruition of free and fair Panchayat elections with significant voter participation, a feat largely credited to Omar Abdullah, the Chief Minister at the time.

Fast forward to 2014, and the reins of Jammu and Kashmir shifted to the BJPDP alliance. Their initial move was bold — dissolving every Panchayat two years before their designated tenure concluded. However, in the face of this administrative manoeuvre, the All J&K Panchayat Conference emerged as a counterforce, recommencing its struggle for democratic representation. On November 5, 2016, a delegation comprising 40 members from this organization interacted with Prime Minister Narendra Modi in New Delhi. They demanded enforcement of the 73rd Amendment of the Indian Constitution, focusing on Panchayati Raj in Jammu & Kashmir.

In response, Prime Minister Modi assured unwavering support and pledged to hold new elections in the state. The elections were declared in 2018, a move catalysed by the collapse of the BJPDP coalition government.

The Unequal Reality

Dr Muzaffar delves into the intricacies of women’s representation in Panchayati Raj Institutions (PRIs), acknowledging the commendable 33 per cent reservation. However, a stark reality persists — women may hold the title but often find themselves sidelined in day-to-day Panchayat affairs, with male relatives assuming control.

Haleema, a 55-year-old Sarpanch from North Kashmir, exposes the disheartening dissonance between official roles and practical influence. “On paper, I am the elected Sarpanch. However, the actual world presents a different image.”

Despite being chosen to lead, Haleema’s husband, Nizamuddin Malik, continues to wield authority, managing official responsibilities and addressing complaints. Justifying his intervention, Nizam emphasises Haleema’s limited education and political acumen, asserting, “She does not know much about politics or the complexities of government.”

However, locals challenge this narrative, arguing that Haleema’s lack of literacy should not preclude active political participation. With proper assistance and training, they believe she can fulfil her duties and make informed decisions for the village.

Similar tales reverberate across the region. Rubeena Akhter, a 35-year-old Sarpanch from Baramulla’s Delina hamlet, acknowledges her reliance on her husband, Mohammad Rafiq Wani, the deputy Sarpanch, despite her matriculation. Rubeena reflects on her unexpected foray into politics, propelled by her husband’s encouragement, stating, “Politics has never really appealed to me. My spouse was the one who pushed me to run for the Panchayat election.”

Contrastingly, Fatah Begum, an 80-year-old Sarpanch of Amargarh, challenges gender norms and age biases. She shares her enduring interest in politics, defying the discouragement prevalent for women. “The new law made it possible for women to hold 33 per cent of the seats in Halqa Panchayats,” she states, highlighting a transformative shift.

Fatah’s journey serves as a potent reminder that age, gender, and educational background should not impede leadership. “I understood that it should not be,” she asserts, emphasising that her experience stands as a testament to breaking barriers and reshaping the world.

In the realm of Panchayats, the glaring gap between formal representation and substantive influence demands a critical re-examination, echoing the broader call for genuine empowerment and equality.

The Vacuum of Representation

Dr Bhat underscores a critical fallout of election boycotts by major political players—entrusting key roles to inexperienced individuals. “Many candidates in Kashmir won unopposed as there was no one else contesting against them, and the voting percentage was also low. Many candidates won by casting their votes and becoming a Panch or Sarpanch. This was the biggest problem in it,” he observes, shedding light on a concerning trend.

In the turbulent landscape of Kashmir, the repercussions of election boycotts echo through the vacant seats. Dr Muzaffar notes that in Kashmir, numerous seats remained unclaimed, leading to their handover to government officers.

In 2018, when the then governor’s administration decided to hold Panchayat elections, the Jammu and Kashmir National Conference and the Peoples’ Democratic Party (PDP) decided to boycott the polls. They wanted to assembly elections first. This triggered a crisis in the PRI systems and a lot of voters stayed away and at places, there was no contest at all.

PDP spokesperson Mohit Bhan defends the decision to boycott, citing the precarious security situation. “In the past many years, we have witnessed how many Panchs and Sarpanchs were killed, and we wanted to ensure that just because to show a political gimmick that we conducted the elections, we did not want to sacrifice people’s lives or put their lives on stake,” Bhan articulates, emphasising the party’s commitment to prioritising people’s safety over political manoeuvres.

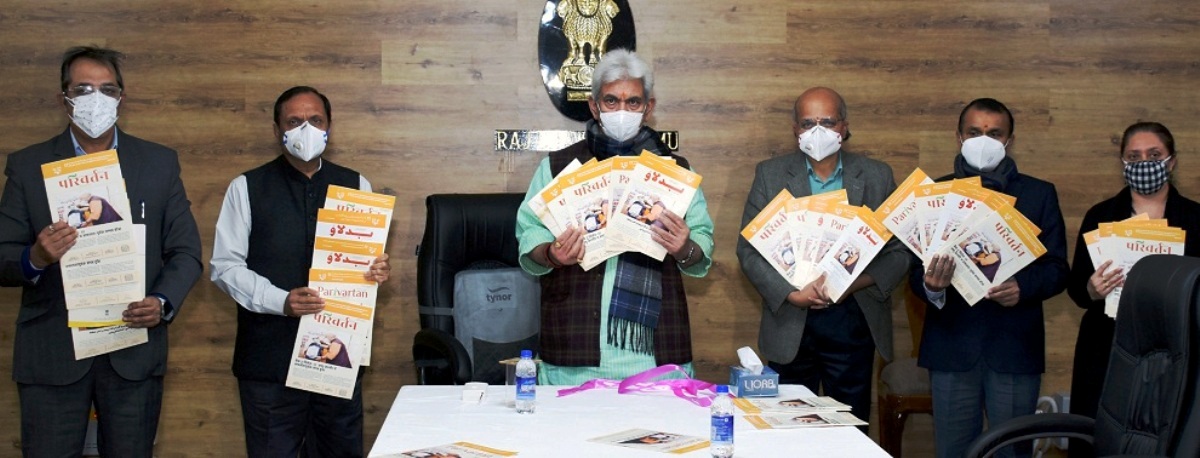

PHOTO BY BILAL BAHADUR

Bhan points out another significant grievance—the lack of inclusive and consultative election processes. “Around 40-50 per cent of seats remained vacant, and at many places, we have seen a lot of Sarpanch and Panch candidates win without any opposition because people were not participating, which shows on the grassroots level, the mechanism was not that strong enough to conduct the election,” he said.

Acknowledging the negative fallout of the boycott, Bhan concedes, “We left the space open, and a lot of nincompoops came and filled these posts and sealed these spaces. That is why we have decided that the party will contest every election.” He emphasises that past experiences demonstrated that those elected uncontested often misrepresented the people.

Highlighting the manipulation of such inexperienced officials, Bhan remarks, “Any delegation which comes from the central government, these Sarpanchs are taken, and they say that everything is fine on the ground, but that is not the real picture.”

In 2019, the then-chief election officer, Shailendra Kumar, highlighted the failure of voter participation as a significant factor leading to the vacant Panchayat positions in Kashmir. The data underscores a stark reality, revealing that around 61per cent of Panch and Sarpanch seats across ten districts in the region remain unfilled, showcasing a notable disparity compared to Jammu and Ladakh, where only 103 and 24 positions remained unfilled. Across 137 blocks, in Kashmir totalling 19,582 Panch and Sarpanch seats, of which only 7,528 were contested, leaving 12,054 (61.5 per cent) berths vacant.

Security Dilemmas

Security remained a perpetual nightmare, even earlier. “Many elected people were taken to high-security areas for some time, and by taking them to high-security, you are taking away from the people,” Bhan said. “And the job they are required to do cannot be done from the security zones.”

Bhan raises a poignant example: a Sarpanch stationed in Pampore despite representing a village in Shopian. “What is the point of conducting this election then? Isn’t this a political gimmick?” he challenges, underscoring the disconnection between elected officials and their constituencies.

Dr Muzaffar echoes these concerns, emphasising the detrimental impact of geographical isolation on the ground-level engagement of elected members. The sentiment is clear—democracy thrives when representatives live among their people, not in fortified zones.

Bhan emphasises the need for a conducive environment where Sarpanchs can actively serve their villages. “It is not that you conduct the election just to check a box and then put this person in high-security areas and allow him once in 15 days for two hours to visit his village and do signatures,” he contends.

Sheeraz Ahmed draws a direct correlation between security concerns and low voter turnout, citing threats that deterred participation across Kashmir. Elected members, he notes, were confined to high-security areas for extended periods due to these concerns.

The spectre of violence looms large over Panchayat members in Jammu and Kashmir, manifesting in targeted attacks by militants. Shabir Ahmad Mir, an independent Sarpanch, fell victim to such an attack in Kulgam, underscoring the perilous environment.

Sameer Bhat faced a similar fate when assailants fired rounds at his house in Khonmoh village, near Srinagar. As the village head of Sarpanch, Bhat succumbed to injuries, highlighting the grave risks faced by grassroots leaders.

Ajay Pandita Bharti met a tragic end at the hands of militants in south Kashmir’s Anantnag district. Reports suggest he had repeatedly sought security due to threats to his life, emphasizing the vulnerability of those in grassroots politics.

The statistics are grim—militants in Kashmir claimed the lives of around 24 Panchs and Sarpanchs between 2012 and 2022. These attacks underscore the formidable challenges confronting grassroots politics in the region, where the very essence of democracy is under threat from acts of terror. “Between 2010 and 2017, there were 32 attacks on the Panchayat members,” a senior officer said. “20 were killed and 11 survived injured.”

Panchayats Under Scrutiny

In unravelling the inner workings of Panchayats, Dr Muzaffar sheds light on a pivotal but underutilised facet—the Gram Sabha or Deh Majlis. “The Gram Sabha is the supreme body to make village development plans,” he informed, noting that every adult in the village plays a crucial role in shaping these plans. However, a glaring gap surfaces as he points out the underrepresentation of women in these crucial decision-making forums. “The lack of involvement of women in Gram Sabha meetings pertains to a significant gap in inclusive decision-making,” he remarks, highlighting a pressing concern.

While the Panchayat Raj Act dictates that any village plan should be crafted by the Gram Sabha, Dr Muzaffar notes a discrepancy between theory and practice. “Whenever one has to do any work in the village, the elected members of the Panchayat have to call Gram Sabha, but the ground is something else here. They sit in a room and make plans,” he observes, underscoring the need for a more robust and participatory process.

Amidst the intricacies of Panchayat governance, Dr Muzaffar raises red flags over corruption and lack of awareness among elected representatives about their powers and responsibilities. He advocates for capacity-building workshops to address these systemic challenges, emphasising the crucial role of informed and empowered representatives.

The scrutiny does not stop at governance intricacies; it extends to the criminal dimension. In a grim turn of events, media reports highlight instances where elected members have found themselves on the wrong side of the law.

One shocking incident involves a Sarpanch, Yashpal of Patrara village, arrested for allegedly shooting his wife, Neelam Devi, in Rajouri district. The complexities deepen as Yashpal, also a Village Defence Committee (VDC) member, reportedly used a 303 Rifle in the crime.

Another incident involves the arrest of four individuals, including a Sarpanch, in connection with the murder of Sunny Saansiyain in the Bishnah area. The assailants, armed with a pistol and sharp-edged weapons, took Saansiya’s life in his own home. Police recovered weapons and a motorcycle linked to the crime.

The controversies don’t end there; a Sarpanch faces legal trouble for allegedly producing a fake caste certificate to contest a reserved seat in the Panchayat election. The case, involving Sarpanch Santosh Kumari, unfolds a web of deceit as government officials are implicated in aiding in the fraudulent acquisition of the certificate. In Budgam a BJP Sarpanch was held for rape.

The intricacies of Panchayat dynamics, both in governance and the legal realm, underscore the multifaceted challenges these grassroots institutions grapple with.

Unconventional Charm in Panchayats

In the tapestry of Kashmir’s Panchayat landscape, a humourous thread weaves through the serious business of governance. Several elected members, albeit not hailed for their oratory prowess, managed to tickle the funny bone of Kashmiris. Take Fayaz Rather, aka Fayaz Scorpio, for instance. His quirky online appearances during the Covid19 outbreak, coupled with his unabashed desire for a Scorpio automobile, turned him into an unconventional figure. Unfazed by criticism, Fayaz Scorpio continues to captivate audiences with his distinctive approach. Off late, he has started endorsing local brands on social media.

In a more serious tone, Junaid Ahmed contemplates a future in electoral politics, driven by a genuine desire to serve his people. Recognising the transformative potential at the grassroots level, he emphasizes, “If a person is dedicated, then he can bring change with his contributions, and Panchayat is the basic level from where one can start.”

Sheeraz Ahmed, acknowledging Junaid’s education and work ethic, sees him as a promising candidate for the future. It is a sentiment echoed by others who appreciate Junaid’s dedication and efficiency.

Looking forward, Rubeena sees her political journey to support her husband’s aspirations. With a conviction that political involvement can enhance their collective impact on the neighbourhood, she emphasises the importance of supporting each other’s objectives.

Dr Raja Muzaffar anticipates a surge in youth participation in upcoming elections, fuelled by dissatisfaction with past fund utilisation. “In upcoming elections, young men and women will participate in Panchayat elections, I believe. The need for greater awareness and educational initiatives to empower elected representatives and foster more inclusive governance is thus the aim,” he asserts, signalling a potential shift in the demographic dynamics of Panchayat politics.

However, the anticipation is met with a dose of reality, as the administration shows no immediate inclination to hold elections. Lt Governor Manoj Sinha cites the ongoing delimitation exercise and reservation considerations as prerequisites for Urban Local Bodies (ULBs) elections. Despite the delays, Sinha highlights the government’s commitment to empowering grassroots democracy in Jammu and Kashmir, emphasizing the transfer of more departments and responsibilities to elected representatives since August 2019. The confluence of humour, aspirations, and the bureaucratic chessboard shapes the intricate narrative of Panchayat politics in the region.

Region Panchayats Sarpanchs Panchs

Jammu 2,135 2,135 20,093

Kashmir 2,177 2,177 17,929

Ladakh 192 192 1,505

Total 4,504 4,504 39,527