A brave widow from J&K’s summer capital, Srinagar, has been fighting against all odds for 19 years to get justice for her husband who was killed only four months after their marriage. She has lost faith in the system but her battle is far from over, Mudasir Majeed reports.

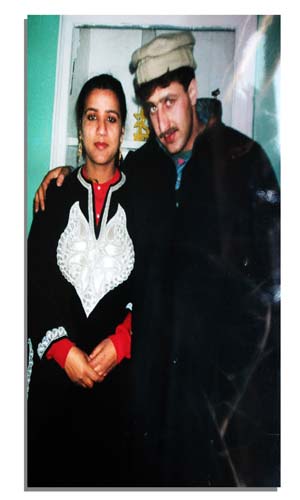

A wedding picture of Munawara Sultan and her husband, Gowhar Amin Bahadur, hangs on a wall inside a large room at Munawara’s three-storied house in Batamaloo on the outskirts of Jammu and Kashmir’s summer capital, Srinagar. Wearing a golden-colored pakol cap, a thick reddish-brown mustache fringing his lip, Gowhar stands close to Munawara with his arm placed over her shoulder.

A wedding picture of Munawara Sultan and her husband, Gowhar Amin Bahadur, hangs on a wall inside a large room at Munawara’s three-storied house in Batamaloo on the outskirts of Jammu and Kashmir’s summer capital, Srinagar. Wearing a golden-colored pakol cap, a thick reddish-brown mustache fringing his lip, Gowhar stands close to Munawara with his arm placed over her shoulder.

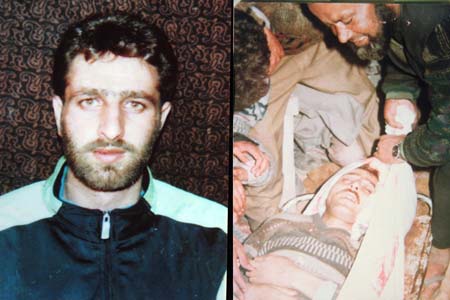

Not even four months of marriage had passed that one more picture was added to Munawara’s photo album. It was the picture of Gowhar’s blood-drenched body, draped in bandages, and his wailing kin circling him. He had been brutally tortured and shot at a cowshed in Banpora, Batamaloo.

At the peak of insurgency in 1990s in Kashmir valley against Indian rule, Batamaloo had become notorious for frequent grenade attacks, IED blasts and exchange of gunfire between government forces and rebels. People from Kashmir’s remotest locations visiting Srinagar were seen bustling in the congested Batamaloo market which also houses Kashmir’s main bus terminal. Gowhar had a shop here in early 1990s where he would sell garments and vend lighting gas cylinders.

On April 7 1993, a powerful landmine exploded near Government Girls High School, Batamaloo, resulting in casualty to government forces. “All entries leading to Batamaloo or out of it were sealed. Security personnel were densely deployed on streets. No movement was allowed until next morning,” Munawara says.

The next day, all male members of Batamaloo including Munawara’s husband were asked to assemble in General Bus Stand, Batamaloo. “Nearly 10,000 people gathered in the bus stand. The action was carried by 4th Battalion of BSF under Commandant G. S. Shekawat and Deputy Commandant, Sanyal Singh. The children had parched due to extended crackdown and search operation, and Gowhar had brought a bucket of water which led to an argument between him and BSF officers. Within a minute, they detained 12 persons and bundled them into gypsies. Gowhar was one of them,” Munawara, now 40, recalls.

This was a time in Kashmir valley when a person picked up from such search operation by government forces had least chances of safely returning home. “Either his family would get his body or they would endlessly wait in the hope of his return. And the worst was hopes were never answered. The wait would end in more wait,” she says.

It was the last time that Gowhar was seen alive. A few hours after the search operation was over, Munawara was informed that Gowhar had been picked up by BSF. “I shrank with fear. The joy of recent wedding started turning into despair. I couldn’t stand up. I froze. But when people gathered around me, consoling me with hope and support, I stood up. We went to Police Control Room, Srinagar. Nayaz Mehmood was Superintendent of Police, PCR and he assured us that he will confirm where Gowhar was taken, but appealed us to stay calm,” Munawara says.

As people including Munawara were waiting at PCR for some news about Gowhar, a group of women from Banpora, Batamaloo sprung from a nearby street, beating their chests, “They said BSF had killed two persons at a cowshed in Banpora. Within minutes, bodies were dropped at PCR. It was my Gowhar and our neighbor, Javid Bakhshi,” Munawara says, adding, “I could do nothing but sit on ground; helpless, crying and plucking my hair. Four months and seven days of marriage and I lost him. His brain was missing. His chest was ripped open with bullets. His clothes were stained with blood. They had murdered him.”

Nineteen years have passed but there is no end to Munawara’s agony. In all these years, Munawara’s consolation has been her son, Anis Gowhar. “I have withered in pain, solitude and helplessness in Gowhar’s absence. Now all I have is Anis. I live for him. I am his mother, his father and friend,” she says. “I am used to solitude now, though Anis comforts me. But sometimes I shrink in corner and sob. I get choked between four walls,” she says and breaks down, her moist eyes turning red.

As I talk with Munawara, a tall boy sporting brownish stubble peeps through the half-open door. “He is Anis,” Munawara says and calls him in. He obeys and leisurely leans his back against a cushion near to me and drops his head forward, as if exhausted by some labor. Anis doesn’t look at us. His eyes are stuck to his cell phone. “The year 1993 was a disaster in my life. One, I married. Second, Gowhar was killed. Third, Anis was born,” she says.

Her words catch Anis’s attention. He smiled and sunk his head into the narrow opening in his Pheran (a traditional Kashmiri gown). “I have a habit of joking with him. He was born eight months after his father’s death. He is 19 today and studies Commerce at SP College,” Munawar says.

Anis grew up at his maternal grandfather, Ghulam Mohammad Khan’s house. He didn’t know his father till he was in Class 9. After Gowhar’s death, Munawara shifted to her parents’ house. After spending 17 years with her parents, she got her own house two years ago, next to theirs. ‘Getting nurtured in the lap of my parents, my son had no concept about Gowhar. But one day he shocked me by asking, ‘Mama, who is Gowhar in the middle of my name, Anis Gowhar Bahadur’. Anis was living under the false notion that his grandfather was his father,” Munawara says.

Gowhar’s death has effected a significant change in Munawara’s demeanor too. She has learned to live like a man. “I stand for justice. I attend two courts, High Court and Lower Court. I go alone. I don’t have any fear. I have been fighting since his death to get his murderers punished. I want to see them die the way they killed him. I know there are less hopes of justice from the Indian judicial system, but I am not giving up, never! If we forgive murderers, they will keep persecuting us. Today if I raise voice against cruelty, tomorrow thousands will join me,” she says with a confident voice.

Despite having witnesses to her husband’s death at the hands of BSF, the perpetrators haven’t been punished. “Once, five BSF men were presented in an inquiry. Among them was the then Commandant G. S. Shekawat. Sanyal Singh, the main culprit has never been presented in court till date,” she says.

“Police station Shergari, Srinagar registered FIR No. 74/93 under section 364/302 RPC on April 1993 in Gowhar’s case but no investigation was carried out. Later in 2007, I moved J&K High Court with a petition in which I blamed BSF for my husband’s custodial killing and sought reinvestigation of case,” says Munawara.

After the judicial inquiry was conducted by Chief Judicial Magistrate Srinagar, Gowhar Amin’s widow says, the High court established that the deceased was killed by BSF in custody. The CJM Yashpaul Bournuey, in his report submitted to High Court, held, “I am of the considered view that the accusations made by the applicant are well-founded and substantiated. She (Munawara Sultan) has produced eye-witnesses who all are local inhabitants of the area, and have categorically stated that Gowhar was lifted by BSF men in their presence and few hours later his body was handed over to police.”

The state government granted her Rs 1 lakh as ex gratia relief and Rs 2 lakh were disbursed to her on the direction of High Court. Moreover, she had been promised a job under SRO but nothing such has happened till date. Munawara has grudges not only against Sanyal Singh and his cabal but against entire India. “India is providing shelter and protection to killers of my husband. I have no reason to love this country. Instead of punishing killers, they have been rewarded,” she says.

Today, Munawara’s faded brown eyes speak of the distress she has been subjected to for all these years. Her fair complexion on wedding picture seems to have darkened with her miseries. When I reached Batamaloo, I found her buying vegetables. A black shawl covered her head. She doesn’t allow Anis to go to market to buy stock for home. She does all indoor and outdoor work herself.

Munawara sold her jewelry to buy an autorickshaw. “The driver gives me Rs 100 per day. With that money, I fulfill Anis’s requirements and mine as well,” she says. As I closed my notebook and prepared to leave, a man wearing a woolen cap entered with a register in his hand, “You have to pay Rs 200. Your November entry is pending,” he told her. As he left, Munawara tells me he was from Mohalla Mahat Committee (A local committee arranging funerals of dead). “I don’t want my funeral to be a burden to anyone, not even my son. I pay Rs 100 per month to committee. They will manage when I die.”

u r real lady…..

love u guddy baji……