The Spanish Flu that brought the world on its knees by killing almost five crore people exactly a century earlier has visited Kashmir also. Though the formal histories have strangely ignored the catastrophe, there are various credible sources offering enough of the detail that Jammu and Kashmir lost almost 40,000 citizens to the biggest pandemic of the twentieth century writes Masood Hussain

The Spanish Flu of 1918 was the world’s last biggest killer. Believed to have killed, anywhere between 50 to 100 million people, the killer flu, that took off as the mass slaughter of the world war subsided and moved across continents.

Though the origins of the virus are unclear everybody knows it was not Spanish at all. “It was mostly called the Spanish Flu, but only because Spain was not involved in the war, which meant that it was the only European country in which the press was open about the outbreak that had been killing thousands of soldiers at the front,” Ali S Khan, the author of The Next Epidemic wrote asserting the virus was the “first strain” of H1N1, that we now know as Swine Flu. “All the combatant nations suppressed the news to protect morale.”

With World War I concluding, the virus took the shipping routes and military transportation to spread and one of the places it reaches quickly was Bombay. It first infected a couple of cops posted at the port facility in June, and then took the train routes to spread around. In three phases spanned two years, the pandemic annihilated almost six per cent of undivided India’s population estimated to be around 18 million (1.80 crore).

Corpses In Ganges

Probably because of the ongoing freedom struggle – that dominated the overall discourse, not very credible information is available about the devastation by the pandemic. Even in post-partition, the research ignored the subject. There is only one PhD on the pandemic impact on India done very recently by a Maura Chhun, a University of Colorado scholar.

Almost every scholar has relied on the biography of Suryakant Tripathi, a poet known as Niralaa, who lost his wife and his many other family members to the pandemic. “I travelled to the riverbank in Dalmau and waited,” Nirala mentioned in his memoir, A Life Misspent (English translation of 1938 Kulli Bhat). “The Ganga was swollen with dead bodies.”

“Throughout the Indian subcontinent, there was only death. Trains left one station with the living. They arrived with the dead and dying, the corpses removed as the trains pulled into the station,” wrote John M Barry in his The Great Influenza – The Epic Story of the Deadliest Plague in History. Insisting that Punjab devastated hugely, Barry mentions a physician’s report saying that hospitals were so “choked that it was impossible to remove the dead quickly enough to make room for the dying. The streets and lanes of the city were littered with dead and dying people. . . . Nearly every household was lamenting death and everywhere terror reigned.”

The book asserts: “Normally, corpses there were cremated in burning ghats, level spaces at the top of the stepped riverbank, and the ashes given to the river. The supply of firewood was quickly exhausted, making cremation impossible, and the rivers became clogged with corpses.”

Jammu Infected

With the virus in Punjab, it was impossible that it would leave Jammu and Kashmir unscathed. There is also not much of the literature available in Jammu and Kashmir to offer a detailed narrative unlike the plague and the cholera epidemics. Even some major historians and the contemporaries have skipped influenza, unlike the plague and cholera. One reason could be that Kashmir was already witnessing a cholera epidemic after a hiatus of almost eight years. But there are enough details that give an idea about how devastating the Spanish Flu pandemic was to Kashmir. Various researchers have done painstaking working to keep certain basics for history.

Jammu, being closer to Punjab was the first to see the arrival of the virus. The additional problem and perhaps the key factor was that Maharaja’s troops – mostly from Jammu and Poonch, were part of the WWII and once it was over, the survivors were on way home.

The seat of power was visited by the pandemic twice. “The first recorded outbreak took place in August 1918. It was rather mild and did not result in much loss of life. The second time, the epidemic was very severe. It started in the middle of October. The first recorded death in the Jammu city took place on the 17th of August,” Jarnail Singh Dev has recorded in his 1983 book Natural Calamities in Jammu and Kashmir. “The transmission of infection by the human agency from the city to the villages was only a matter of days and the disease soon penetrated into the remotest parts of the State.”

Singh gives interesting details of how the depot’s administration tried to control the epidemic. It was then called ‘war fever’ because it emanated at the conclusion of the Second World War. In India, it was known as Bombay Fever, however.

Immediately, Maharaja’s Wazir of Kathua sought permission to close schools and offices for 10 days. A similar request was also made by his Mirpur counterpart. This makes it clear; Singh asserts that the epidemic was raging in all the parts of the province.

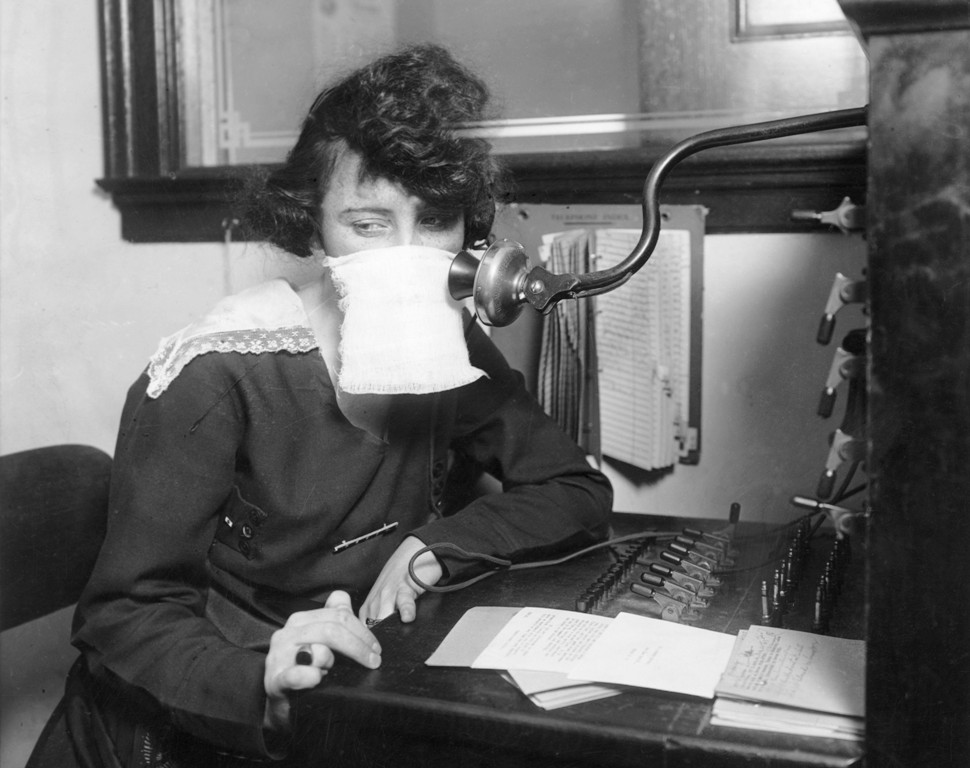

“The only known medicine was quinine (it was being used for malarial fever). The Government of India issued an influenza vaccine invented by the Central Research Institute at Kasauli to the affected states,” Singh has recorded, after consulting the archival records. “The vaccine was to be administered in two doses with an interval of seven to ten days between them. When, for expediency, a single dose was to be given, it was to be larger than the total of two dozes.”

But the vaccine was of no great help. There are no records about how many people were given the vaccine. The death was dancing everywhere though the exact count is not known to Singh. “The total number of deaths in Jammu city with a population of 31000 was about 686, while the figure for the Jammu province excluding the city was reported to be 7988,” Singh has recorded. “The highest daily morality of 38 was recorded within a fortnight of the outbreak of the disease. These figures seem to be incorrect because there was no proper arrangement for recording the deaths.”

Virus In Kashmir

The Kashmir part of the story was slightly different. The virus infection appeared in the middle of August 1918. After some time, it subsided, only to return again in October. The virus exhibited the same pattern almost everywhere. By the fall – around November, the aH1N1 had reached Kargil and Leh too.

“The mortality in Kashmir during the second visit of the disease was very high. The total number of deaths according to Chief Medical Officer’s estimate was 15000 against 7007 reported by the police,” Singh has recorded. “The police report was not considered authentic as they did not perform their duties properly and the public also did not register the exact number of deaths with the police chowkies.”

Officially, the Srinagar Municipality has recorded only 176 deaths from peculiar influenza – mostly based on police records. However, the Municipality President, as recorded by Singh talked about “at least 1000” deaths in the city. Unlike the rest of the plains and offshore locations, the Spanish Flu dominated Kashmir scene till early 1921.

Anita Devi, a Jammu historian who has done impressive research on the health issue has made two important points. The Flu pandemic came at a time when Kashmir – at least parts of South, were already under the grip of a Cholera outbreak.

“The total number of deaths for Jammu province was 8674 and for Kashmir province, it was about 15000,” Devi has written, based on first-hand research. “Towards the close of the year 1925, it again reappeared in a mild form in Srinagar city and cases were also reported from tehsils of Ladakh and Kargil. But the infection died out immediately and the total number of cases and deaths reported was 1384 and 36 respectively.” The virus had mutated and apparently the herd immunity had emerged on the scene.

44000 Deaths

Apart from police records, the yearly administration reports of the depot’s government and the records of Chief Medical Officer lying in the archives at Jammu, the key source on the basis of which the assessments of the damages of the Spanish Flu were made was the census of 2021.

Vinayak Razdan, an avid Kashmir blogger, however, says the human costs of the pandemic were much more. He has used the decadal census to put his point across. “The total mortality from Influenza in the Jammu Province (excluding the city) during the period of four months is reported to be 7988, but these figures are undoubtedly unreliable, considering that the number of deaths in Kashmir where the epidemic was believed to be less virulent and fatal, amounted according to a rough calculation made by the Chief Medical Officer, to 15000,” Razdan has recently written. “This assumption receives further support from the fact that the total mortality from all causes in the Province (including the city) in 1918 stood at 49800 against 25817 and 2I844 respectively in the two years immediately preceding and succeeding the year of Influenza.”

Razadan has mentioned the 1921 census report that suggests that in Jammu and Kashmir 88291 people were consumed by four epidemics – the plague, cholera, smallpox and influenza. The Influenza, that then was nothing other than Spanish Flu, has killed 44514 people including 15000 in Kashmir, 8507 in Jammu, 19375 in Poonch, and 1632 in Bhaderwah.

Great Doctor’s Death

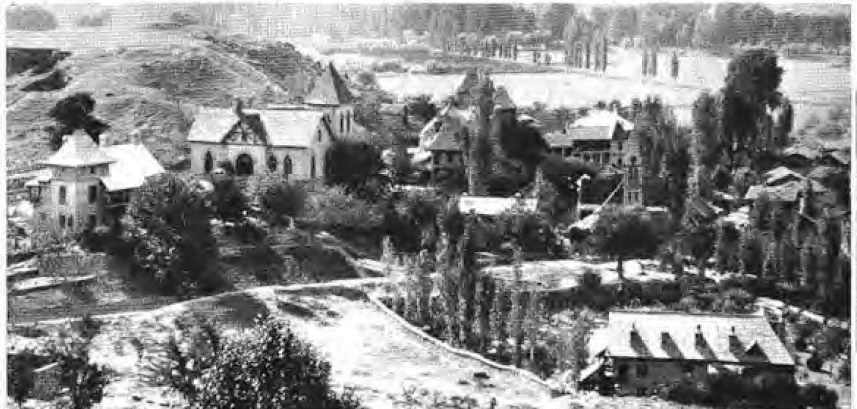

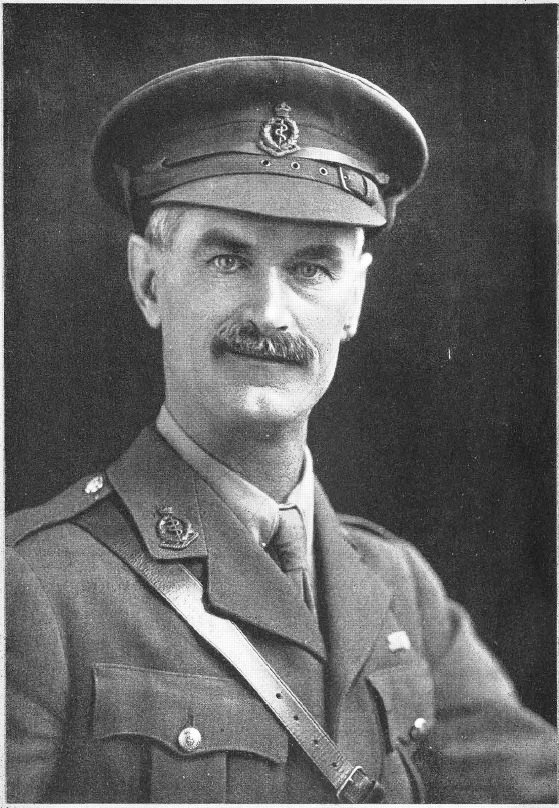

What is interesting and is that Dr Arthur Neve, one of the two Neve brothers to whom Kashmir owes its modern healthcare set up, died of fever on September 5, 1919. He was laid to rest at the Christian cemetery in Sheikhbagh with full state honours, a Kashmir shawl spread over his coffin. Thousands of people joined his funeral procession in acknowledgement of his unmatchable services to Kashmir. Maharaja personally condoled the death of his “old friend”.

Dr Arthur Neve joined the medical missionary services in Kashmir in 1882. Four years later, he was joined by his brother Dr Earnest F Neve in 1886. Till his death in 1919, Dr Arthur wrote a number of narratives on Kashmir including a tourist guidebook that had almost 20 editions till his death. In 1914, he offered his services to the colonial army in WW2 and was taking care of the soldiers. In 1918, he shifted to France literally on the battlefront. A year later he was back home to Srinagar where his absence was felt seriously by the society.

His homecoming was celebrated by Kashmir. “In mosques and temples services of thanksgiving were held for his safe return,” A P Shepherd has recorded in Arthur Neve of Kashmir. “He looked but little older, thinner perhaps and paler, and with a slightly more military cut in his moustache; but as always he seemed the very embodiment of life and activity.”

“At the end of August 1919, Arthur Neve was suddenly struck down by fever. The nature of this was obscure, but it appeared to be related to a severe attack of influenza, from which he had suffered when in France,” his brother, Earnest F Neve wrote in A Crusader In Kashmir. “Owing to his recent strenuous life, resistance to infection had been greatly lowered. Endocarditis supervened; his condition became critical, and he passed to his rest, after many hours of unconsciousness, on 5th September.”

Shepherd, however, has used Mrs Neve’s accounts indicating Dr Neve actually died of influenza.

Seemingly he was Kashmir’s top victim to the Spanish Flu that originated formally from France. “Congregations of Moslems, to whom, in their mosques, the intelligence was imparted, were moved to tears. The funeral was like a triumphal march. For once there surged up to the surface some indication of a widespread appreciation of his long life of service rendered to the people.”

Virus Returns

A century later, the aH1N1 is not dead. It survived in Kashmir as it lived in other parts of the world. The last outbreak was reported in Kashmir as recent as 2009. A decade later it has returned with a big bang. Like commoners, healthcare workers are also getting infected.