Most of the epidemics that Kashmir history has witnessed were imported and they thrived on unhygienic environs, indifferent rulers and a superstitious clergy, reports Masood Hussain

Aware of the ragging plague in Rawalpindi, Jammu, and Poonch, authorities in Kashmir put additional staff at the entry points in 1903 to prevent trespass. On October 9, as recorded by A Mitra, the then Chief Medical Officer in The Indian Medical Gazetted (April 1907), panic spread when a suspected plague case died in Uri.

On November 13, a tonga carried a veiled woman along with her two servants. “The inspectors failed to detect the disease. The order to them was to take the temperature of every traveller,” Mitra wrote. “Their subsequent report showed that all the occupants of the tonga at the time of inspection had a normal temperature.”

The tonga carried the plague to Kashmir. On November 18, a person with high fever, “anxious look, slightly wandering mind, inguinal glands of both sides swollen” was found outside the State Hospital in Srinagar. He had been left there by “a hired pony-man from Kralpura”. The person identified himself as Mrs B’s servant, the same veiled lady in the ill-fated tonga. A Kashmiri resident, Mrs B was shuttling between her Rawalpindi and Srinagar homes.

Immediately, the patient was removed to an isolated tent, outside the city. Investigations identified the two individuals as Ghulam Mohammad, the cook, and Abdul Rahman, the khidmatgar. On November 16, they had reached Kralpora and stayed with Subhan Bhat, Mrs B’s relative. For three days the sick cook remained restricted to a small room in Bhat’s ground floor. He died on November 19. By then various people, mostly grain-dealers had visited Bhat.

Cook’s body was buried in a 10 ft deep grave, carbolated with lime; everything that the cook had touched was burnt and all the persons – a hospital assistant, a khidmatgar and a sweeper, who had contacted him were isolated. Bhat’s Kralpora home with everything in it, including the grains, were burnt to ashes. Mrs B, her servants and the Bhat’s family, the pony-man, were admitted kept in hospital quarantine. None of them developed plague, however.

Kashmir still got the plague. On November 25, one of the four constables who were deployed to restrict the sick cook in the isolated tent fell ill. “When I saw him in the evening, I found him slightly delirious, and I thought the man had pneumonia from exposure to the severe cold of November in an open field. There was no glandular enlargement,” Mitra recorded. “He died at night. When I heard of his death, I suspected pneumonic plague. The body was accordingly buried in a deep grave in an open ground.”

Mitra recorded that the cop, along with his brother, a hospital attendant managing the plague cases, had gone into the tent and handled the corpse. “It is further said, that he put his mouth on the finger of the deceased to bring out a ring, biting it with his teeth,” Mitra wrote. “If this story is correct, which I believe it to be, plague commenced in Kashmir from a crime.”

Soon his medical attendant brother went missing and was never recovered alive. In the next six days, the dead cop’s family, including his father, mother, sister, wife and children and a sister-in-law, annihilated. With the police help, the family had exhumed the cop’s corpse and brought it home for re-burial in their family cemetery. They had done the same thing with the medical attendant who had died at a relative’s home at Geru, 17 km away from Srinagar, near Tral. Then everybody who had any contact with the particular family contracted the plague.

Authorities identified the homes where the plague cases lived and set them afire. “Where this was not possible, it was infected by perchloride of mercury, door and windows were left open, holes were made in walls and roofs, and the main door was closed up and guarded,” Mitra recorded. “Temporary huts were raised to house the infected and tight guard was posted.”

This marked the beginning of the plague that last a year. Outside Srinagar, Geru became the first victim. The cop’s relative, the village Lambardar, the richest man in his area, died first and was followed by his three sons. “This man had relations far and wide in this and neighbouring villages, who came to sympathise with the family,” Mitra reported. “From Geru it ‘spread to Cluirsu, from Charsu to Sail, and so on till it reached Tral, a very populous village 20 miles from Geru.” The government destroyed those houses and where it was impossible, they were disinfected.

Soon, people started dying in huge numbers. In Srinagar, authorities, hired eight coolies, inoculated them with Haffkine’s prophylactic, and engaged them for disposal of the dead. Despite inoculation, one of them contracted the infection and died within 21 days.

Another relative of the constable took the plague home to Kripalpur (Pattan). After immediately disappearing, the plague recurred in a village on the Wullar lake shores, where it killed many people. They all had helped in the burial of a guest who had come from Geru to Gund Jehangir.

However, Shahgund and Bijpara villages near the lake proved stubborn plague centres. Shahgund proved unfortunate as it lost 269 people to the plague leaving barely 600 in 125 homes. Finally, the authorities completely relocated them to an open ground camp with enforced social distancing and removed the thatch roofs of their huts thus enabling sunlight to get in.

Mitra recorded that people were unsupportive: “The superstition of the people was that the police constables and their relations were only suffering for their sins. Many educated people, from whom better things were expected, actually tried to rouse popular opinion against us by making false representations about discomfort in the camps and spreading the rumour that it was only pneumonia and not the pneumonic plague.”

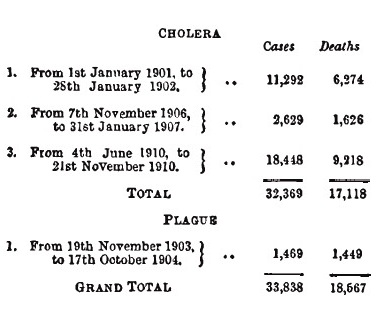

Plague Losses

By 1904 autumn, when the plague was effectively controlled, Kashmir lost 1449 Muslims including 1314 in the periphery. Unlike Kashmir where most of the infected died, Jammu witnessed only 329 deaths in 489 cases. After the plague abated, inoculations started. Of the 352 inoculations in Srinagar, 10 were Europeans, 149 were Muslims and 190 were Hindus. The 1911 census attributed the fall in the population growth of Mirpur and Jammu to the plague and cholera.

In Kashmir’s tragic history of calamities, the plague has been an occasional “guest visitor”. In Mughal era, the plague crisis led Jehangir record the tragedies it inflicted in 1615: “Things had come to such a pass that from fear of death fathers would not approach their children and children would not go near their fathers.”

When the wily mercenary, Alexander Gardner, was passing through Srinagar at the peak of Sikh misrule when Kripa Ram was the governor (1827-31), he saw Kashmir in the grip of a serious crisis. An earthquake had killed some 12000 residents. “The stench from the corpses was frightful, and the survivors were afraid to bury them,” Gardner was quoted saying in Soldier and traveller; memoirs of Alexander Gardner, Colonel of Artillery in the service of Maharaja Ranjit Singh. “In consequence, a kind of plague broke out in a few days, people fell to the earth with vertigo and nausea, and their bodies turned black.”

The Resident Killer

Kashmir’s real ‘resident killer’ was cholera, an epidemic that accompanied the rulers and their armies to Kashmir. Quite frequent since the Afghan era, Kashmir would routinely end up losing not less than 10,000 people to every epidemic.

These epidemics maintained peculiar characteristics throughout. These were diseases imported by the visitors, pilgrims or the soldiers from the plains of Jammu or Rawalpindi. Once brought in, they would thrive on three key factors – a dirty and unhygienic Srinagar, an indifferent ruler lacking local stakeholding and the superstition enforced by the clergy. In certain cases, the rulers would ensure slaves do not get medical help.

Closing A Dispensary

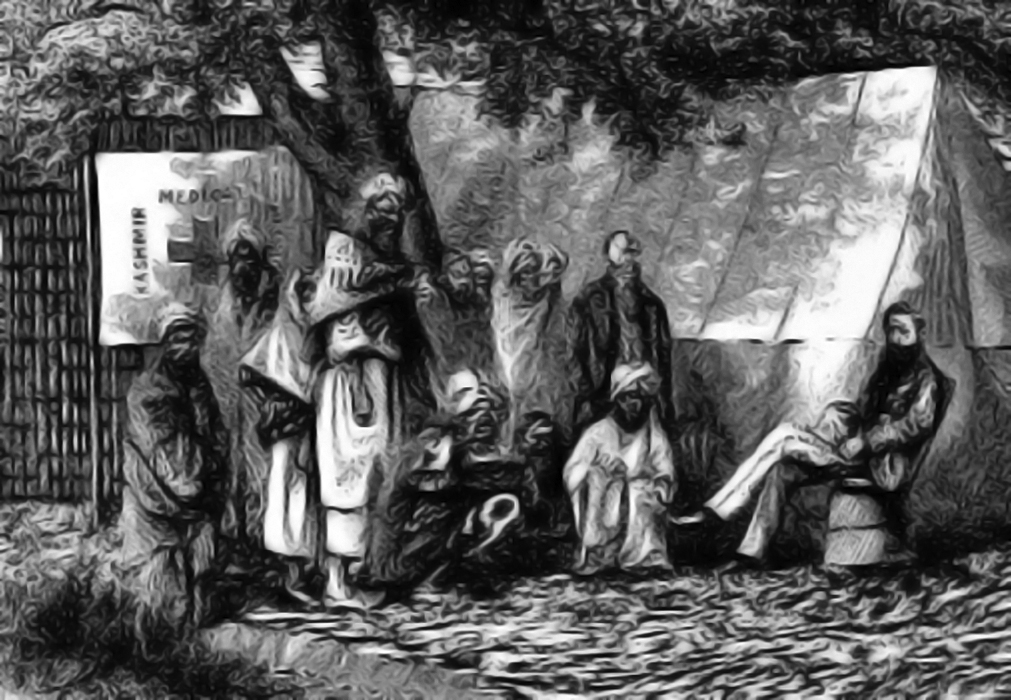

To every pain-giver, however, there has always been a healer around. One of many benefactors of Kashmir was William Jackson Elmslie (June 29, 1832 – November 18, 1872), a Scottish Presbyterian doctor who introduced the modern healthcare in Kashmir from 1865 till his death. His Srinagar dispensary was operational by May 1867 but “the native Government do all in their power to oppose me”. As Cholera broke out by killing six soldiers on June 16 (soldiers had brought it from their pilgrimage to Haridwar), his dispensary, located in European quarters, according to his memoir Seedtime in Kashmir, was closed down.

On July 9, he wrote to Mrs Cleghorn: “It appears that the local Government and the Mussulman Mullahs are now greatly afraid of us, especially as two of their priests have become Christians. The result of this fear and hatred has been great hostility and opposition to my work. From the very beginning of the season, sepoys were placed at the entrances of all the avenues leading from the city to the European quarters. These sentries confessed themselves that their orders were to stop the sick from going to the Padre Doctor Sahib, as they style me. Some were allowed to pass on, giving the sepoys some money; others who were caught coming to me were roughly handled and beaten, some were fined, and others were imprisoned.”

After closing the dispensary, what did the Maharaja do? “We translated a charm against cholera which has been issued by order of His Highness the Maharajah,” Elmslie recorded on August 1, 1867. “Each copy is sold for four annas. It directs the possessors to perform certain acts of worship and to give alms, assuring them that in so doing they are safe from the plague.” Being marketed through government offices, the “curative and preventive” manthar was to be repeated, and pasted above the doors of the houses!

Sometimes, the rulers would hold the subjects responsible for the epidemic. Hasan Khuihami’s Tarikh-i-Hasan mentions that in 1845 cholera, Samad Baba Qadiri, a resident of Chhattabal, was burnt alive in cow-dung for his alleged crime of cow-slaughter along with his 17 family members under the supervision of Bhola Nath, the Thanedar.

The Rough Notes of Journeys Made in … 1868, ’69, ’70, ’71, ’72 &’73 in Syria, Down the Tigris, India, Kashmir, Ceylon, Japan [&c.] author has remained anonymous despite being key witness to the 1872 epidemic. “They tell you here that cholera comes only with famine, but there is no famine at present here, and still the deaths from cholera number sixty daily,” he recorded on August 14, 1872. Next week he was in Islamabad (Anantnag) where he found on August 21, that “an order from the Kotwal has gone forth that the whole population, Mahometans and Hindoos, men, women, and children, shall for three days employ all their time in prayer.” The next day, the Kotwal lost his wife to cholera.

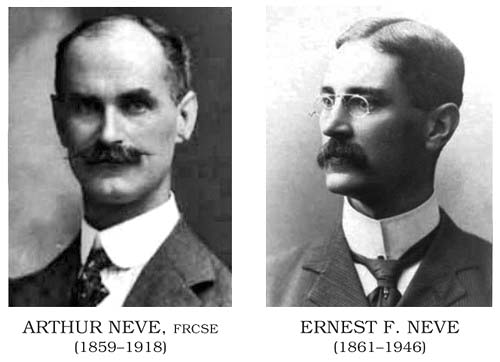

The Neve Brothers

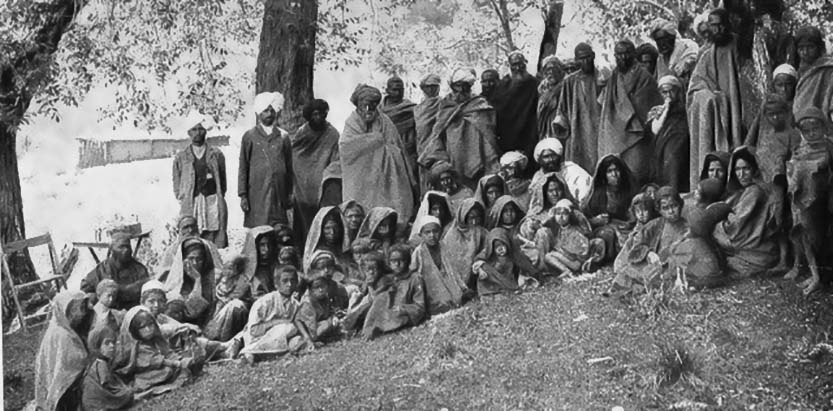

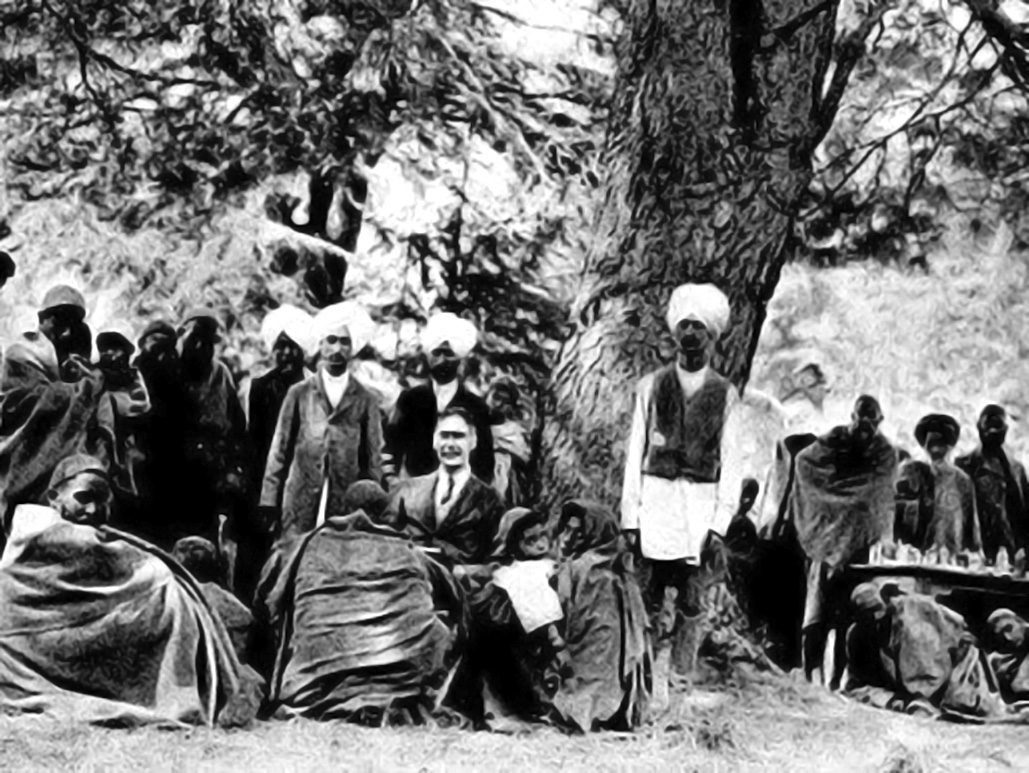

Brothers Dr Arthur Neve and Dr Earnest Frederic Neve laid the foundations of the formal hospital in Kashmir. Arthur came 1882 and Earnest joined him in 1886. They gave their lives to Kashmir. The brother had the distinction of visiting all the Cholera impacted districts in the summer of 1888. They traced the epidemic sources.

“The court left Jummoo in March and travelled on slowly via Punch, and Baramulla. The traffic on the direct route from Jummoo via Banihal was at this time considerable, and among others, there was a party of several hundred Hindu pilgrims,” Arthur wrote. “Cholera broke out on both sides. At the time when the Maharaja arrived in Baramulla, there were several cases among the camp followers and coolies… It must have been the 5th or 6th of April as far as I could ascertain on the spot three weeks later, that cholera stricken Hindu died at Shahbad, a large village at the foot of the pass. The following day, a peasant of that village was attacked, and the epidemic began to spread.”

While the entire Kashmir between Shahbad and Baramulla was caught in the crisis, the movement of a regiment to Shopian hills took the epidemic to these villages.

Dr Enrnest Neve was in Kashmir for many decades. In 1888, he recorded a hundred deaths a day in the city. He saw closely how the superstition was playing against the logic. “It is the shrine which protects from disease and disaster, and to it, they look for aid in any enterprise or in times of stress,” he wrote in Mission Hospital Reports. “One of the villagers, referring to the plague, which had not invaded the isolated mountain district in which his village was situated, said to me, “It has not come here, sir, the Pirs here have mighty powers.”

Superstition, Neve said was the major contributor to deaths. “On one occasion, for instance, the Mohammedan priests of a famous shrine made a proclamation that to avert the pestilence; the tank in the courtyard of the sacred edifice should be at once filled with water brought by the worshippers. The people came in their hundreds, each bearing a water-pot which was duly emptied into the tank, some of the water of which was then drunk as a preservative from cholera. Unfortunately, the water was infected, and the disastrous outburst of cholera which followed was acknowledged even by the Mohammedans to be obvious due to the work of the previous day.”

Cholera attacked Kashmir five times – 1888, 1892, 1900, 1907 and 1910, in twenty years killing at least forty thousand people. In 1888 and 1892, Neve said Srinagar was a City of Dreadful Death. “In some houses, one by one all had been attacked, and the last survivor was left with no one to attend and give food and water. The village official who reported the cases had just died. The head-man of the village refused to move out of his house, and panic was universal,” Neve described the scene in Lolab belt in 1907 epidemic. “Many of the village springs became veritable death tanks.”

Beagaar and Cholera

The governance structure, however, managed its exploitation amid an epidemic. In May 1888 when hundreds were dying every day, Neve was on cholera duty in Islamabad, where he was shocked to see a levy of 5000 or more coolies assembled in a ground. “The villagers were almost distracted with fear. Who would do all the agricultural work? What would happen, during their long absence, to their wives and children? To what perils of pestilence and inclemency of weather would they themselves be exposed in the crowded bivouacs and snowy passes of the deadly Gilgit district?” Neve wrote. “I was present at a sort of farewell service on a maidan outside Islamabad when nearly 1000 men were starting. And when they took leave of the friends who had accompanied them so far, loud was the sobbing of some, fervid the demeanour of all as, led by the mullah, they intoned their prayers and chanted some of their special Ramzan penitential psalms. Braver men might well have been agitated at such a time. It is certain that cholera clung to the camp, and that unburied corpses of hundreds of these poor begaris marked the whole line of march from Srinagar to Bunji.” Originally known as Bawanji, the Astore cantonment marked the end of Dogra rule. Kashmir’s oldest saying – Baratha Bawanjan (should I sent to Bawanji) is linked to this spot, a reference to the Beagaar system.

The famous Settlement Commissioner, Sir Walter Ropert Lawrence was camping in Kashmir during the 1892 cholera outbreak, the worst of the town epidemics since 1824 in which he believes more than 18000 people died. “All business was stopped, and the only shops which remained open were those of the sellers of white cloth of winding sheets. Men would not lend money, and in the villages, the people would sit all day long in the graveyards absolutely silent,” he wrote in The Valley of Kashmir. “Men telling me how they had lost all the members of their family would break into hysterical laughter, and I have never seen such utter despair and helplessness as I saw in 1892.”

Official records suggest that a traveller from Lyallpur District died of cholera on the Banihal road and within a day a number 4000 coolies working on a new road were affected. Of 200 infected workers, 176 died instantly.

An Enquiry

British India government deputed Surgeon Colonel, R Harvey to investigate the cholera epidemic and his findings were shocking and interesting. Lamenting over London’s “greatest mistake” of the selling the Elysium on Earth, as Thomas Moore once sang, to the Jammu Maharaja, Gulab Singh, the British doctors told the British Medical Association meeting at Nottingham (UK) in August 1892 that a road for wheeled conveyance has come up recently as a natural consequence of a growing increase of traffic and now been opened, with a great and “as another consequence, an increased liability to imported disease”.

Harvey’s report said in 1843, Cholera has killed 20,000 people in Srinagar, and lot many in 1870; almost 10,000 – 3500 of them in Srinagar in 1888. “Severe epidemics, then, are becoming more frequent, and the intervals between them are shortening,” Harvey reported. “To those who believe, as I do, that cholera is not an airborne poison, but is invariably carried by human intercourse, the opening of the Jhelum valley road makes it absolutely certain that the danger of the importation of cholera germs has increased, is constantly increasing, and cannot be diminished.”

A Dirty Srinagar

The imported germs found perfect soil to prosper. It quoted various officials to explain that Srinagar’s “unsanitary condition” and “filthy habits” of residents are “proverbially notorious”. He found the “badly built” town with torturous paths, without any drainage and ‘unswept’ from ancient times. Dr A Mitra told him: “..Barustal-gus (filth at the door) is proverbially admitted to be a mark of affluence. Human ordure is scattered broadcast all over the town. From the roads and houses on the river bank drains carrying slush filth and sewage empty into the river, in which the washermen wash unclean clothes, the dyers wash their dyes and the butchers’ entrails of animals. The consequence is that the water of the river, as it flows through the city, is little better than liquid sewage.”

Then, the Maharaja’s government had appointed fifty sweepers (scavengers) for conservancy work over an area of about four square miles for eight months in a year. Harvey concluded: “It is not too much to say that the inhabitants eat filth, drink filth, breathe filth, wear it, sleep on it, bathe in it, and are steeped in and surrounded by it on every side; and till this state of things is altered, it is as certain as fate that epidemics of cholera at shorter and shorter intervals must continue to recur.” The doctor gave the credit of importing the fresh phase of cholera to the ruler, asserting: “In 1888 the disease was imported from Jammu by His Highness the Maharajah’s camp.” The British India investigator followed the chronology of the camp’s movement into Kashmir and that of the cholera cases reported accordingly.

How it impacted Kashmir. “The type was about as malignant as I ever have seen; 65 per cent, of the Srinagar cases, died, and at height of the epidemic as many as 40 per cent, of the cases died within 24 hours. Every part of the city suffered; there was hardly a house where there was not one-or dead, whole families being swept away in some instances,” Harvey recorded. “A complete panic took possession of the people. The shops shut, the streets deserted, and business entirely suspended. The officials whose duty it was to distribute food from State granaries to the poor, of whom there are 30,000 to, refused to leave their houses, and the people unable to get grain were driven to eat all sorts of unwholesome food, thereby rendering themselves more obnoxious to attack.”

To the joint efforts by the medical staff and the Maharaja’s government, ‘carelessness, prejudice, negligence and superstition’ played the spoilsport. The officer recorded: “Very many of the sick absolutely refused all medicine, on the ground that if God had willed them to die they had to die and if to live medicine was unnecessary. Others pretended to take it, but did not do so; many had themselves bled to fainting, and hundreds took purgative medicines to carry off the disease in that way.” Harvey found the visiting European community in Srinagar had been relocated to Gulmarg, despite that some of them died of Cholera.

Harvey did make a set of suggestions to prevent a recurrence. But he was aware of the limitations of the British resident because the entire power rested with “His Highness the Maharajah”, whom he described as “an orthodox Hindu of the strictest kind”, asserting that his Council does have some “educated and enlightened men” but doubted that “if any of them will oppose the known wishes of the Maharaja”. He found the Srinagar Municipality lacks funds to do anything beyond managing its scanty staff.