When a mischievous boy with Afghan blood was forced out of a seminary at the age of 14, he broke down and instantly turned into a poet. He inherited carpentry to look after his family but never gave up his passion for creative poetry. Now the man lives a satisfying life as he might be one of few poets who sell in Kashmir, reports Samreena Nazir

Managing his day’s fatigue with the sips of Nun Chai after returning home from his work, he often raises his finger and writes in the air.

Carpenters generally carry pencils on their ears to mark the wood sheets they work on. So does Sajad Husain. But apart from marking wood sheets, Sajad gives life to every breeze that flows through his mind, with that pencil. Sajad is a professional carpenter and a passionate poet, a poet-carpenter actually.

“I usually write my poetry on the scrap wood while working and then return home with that particular bit of thin wood to copy my lines from it”, the 52-year-old Sajad Husain Najar, said. With seven poetic collections to his credit, he is popular as Sajad Inqilabi.

Sajad has an interesting life. His family history is equally different. Before 1947, a labourer from Afghanistan Jabbar Khan came Kashmir. For most of the medieval history and even earlier, Afghan would come to Kashmir for work, loot or simply to misrule. Kashmir’s Afghan rule is one of the worst. But open borders would rarely prevent fugitives from the law in Kabul to take refuge in Kashmir.

Whatever the reasons for Jabar’s Kashmir arrival, he was caught by the situation that evolved here. India and Pakistan bifurcated into two countries and the first major exercise they undertook was they clashed over Kashmir. This led to the closure of all the borders and Khan was stuck up in Kashmir.

With no possibility of return, Khan decided to make Kashmir his home. He married in a Dar Family at Khudwani (South Kashmir). Inqilabi was born as his grandson in May 1964.

Possibly because of poverty or some other reasons, Inqilabi was given for adoption to Ghulam Mohiuddin Najar, a resident of Takiya Behram Shah, also in Islamabad.

https://www.facebook.com/KashmirLife/videos/1702306639818728/

In his childhood, Sajad admits, he was notorious for his mischievous behaviour. Every day after having fun with his friends, he would return home with a lot of injuries and scars all over his body. His adopted parents were genuinely bothered about him. They finally admitted him to a local Darsgah for Quranic education. But the fate had something different for the boy. The headstrong child was eventually thrown out by his teacher for asking, what Sajad said, irrelevant questions. He remembers that he was in his twelfth year of age at the time of this crisis. He also remembers that he felt heartbreak for the first time.

This incident, Sajad said, led him to discover himself as a human being. It was 1976. When he reached home, he was in a bad condition. He felt pained and humiliated.

“I left the Darsgah with swollen eyes and holding the Quraani Qaidah in my hands,” Sajad said. “When I reached home, I gave my crisis the words it required.” He wrote:

Haefiz Quran Waale, Kourtha Tche Zanh Wazean Aeth,

Parha Alif Teh Thar Cheaum, Goub Goustch Neh Baar Aaasun

(O God, the memoriser. Have You Ever Weighed the Quran. For I want to recite the Alif buy am scared of its mass.)

Laam Gov Kamal Waarah, Zeave Gaye Sharmeh Daawaie,

Yeli Meem Kanov Tche Bouzekh, Zuv Goutch Nisaar Aaasun

(To me the value of Laam is too huge and my tongue is extremely shy. When you would hear me reciting Meem, I must give my soul in sacrifice.)

Wugraaie Yiekh Teh Wenzeum, Douh Khand Brunhie Te Kyazai,

Yeli Yikh Teh Nikh Amanath, Beh Gosus Tayaar Aasun

(When you would send for taking away my soul, is there a possibility to get a notice of a day so that I am ready with the debt I owe you)

Praraan Cheh Paaneh Sarkaar, Firdous Teh Houzi Kounsar

Yeli Kholeh Meon Daftar, Pateh Gous Neh Naar Aasun.

(Waiting there the Almighty, in heavens with eternal bliss. But when He opens my records, O God, there should not be hellfire)

Like every other parent, Sajad’s parents too wanted him to study and help him live a decent life which they themselves never enjoyed. They sent him to teh school where he took his studies seriously. But his father had a responsibility of five daughters, in addition to Inqilabi and his younger brother. His father could hardly earn from carpentry beyond what was required for feeding the large family.

This situation urged Inqilabi to discontinue his studies and drop out completely. By then, he had reached his middles. He left his school bag and took a bag full of carpentry tools. But one tool existed in both the bag, his pencil. It was this tool that connected his two worlds, his profession and passion.

“I was barely 14 when I read Mushtaq Kashmiri’s Shour-e-Muhshar. There was a poem Monde Hinz Eid (the Eid of a widow) which made me restless,” Inquilabi said. “For many days, my eyes kept shedding tears. That poem had a strong impact on my mind and then I read anything and everything that Mushtaq Kashmiri had written including Sur-e-Israfeel and Sal Sabeel.”

For Inquilabi, it was not an easy thing to give a vent to the artist inside him. For the whole day, he would sweat in physical labour. And then in the evening, he would unleash his poet on his person and garnish his thoughts.

Later, when he got married, he was blessed with three daughters. His requirements and tensions increased with the passage of time. He continued living a life of deprivation.

Inquilabi had limited earnings and huge requirements. He also wanted his poetry to be published. He had not enough money to get his poetry published and approached few copyists to write his work but was unable to pay them. Those day, he admits, were days of his penury.

“I was not in a position to feed my family properly,” Inquilabi said. “It was harsh winter and days without work as construction had somehow gone down. So I decided to learn calligraphy (kitabat). I used to go Cheeni Chowk, Islamabad to learn the art of from Mir Ghulam Ahmed. Before leaving home in the morning, my wife would give me a list of things to buy from the market, but empty-pocketed, I would always return empty handed.” As Inquilabi was talking about those days, he would not move his eyes from his wife, who was sitting near him. His eyes were still tearful and it seems as if he would break down.

“It is believed that a son keeps the name of his parents alive but we don’t have a son but still his poetry is going to keep him alive,” Naseema, his wife said. “I know it, he will be remembered for his work.”

Inqilabi has six books to his credit and is working on the seventh one. His books reflect his thought on social, political spheres of Kashmir and the ongoing conflict. In his book titled Zakhmeach Zuag, Inquilabi has captured the condition of society like this:

Bae’tch Travith Rae’tch Raave Aareh Maenz,

Zoon Gaashus Khoun Peovyie Na’ar Maenz

(You left behind your family and spent your night in desolate grounds and the moonlight saw your blood spilling over fire)

Chum Neh Muloom, Chuie Katen Tche Madguza’ar,

Potreh Ga’asho, Chum Dil Tawai Beikaraar

(Son, My heart is restive because I am unaware where your burial place is.)

Maaleh Myanev Ctxaleh Kos Yuith Heou Jinaaz

Raj’eh Gobra Majeh Tcxoni Krehanmaaz.

(Son, who father can bear a funeral like this. Do you know your mother’s heart has ruptured in pain.)

Inquilabi’s poetic talent worked as a kick in his economic standard and made him able to bring up his daughters with ease and provide them an education. “People liked my work and I was appreciated at every step,” admits Inquilabi. “It boosted my income Alhamdulilah. I earn Rs 40-50 thousand for every book, as I don’t have to pay for its calligraphy because I do it myself.” Of his three daughters, one is settled and is working with a bank. Two are grown up and studying. Inquilabi and his family live a satisfying life.

But how often does his write his poetry? Inquilabi said unless he doesn’t get a subject which is inspirational and satisfactory, he is not able to write.

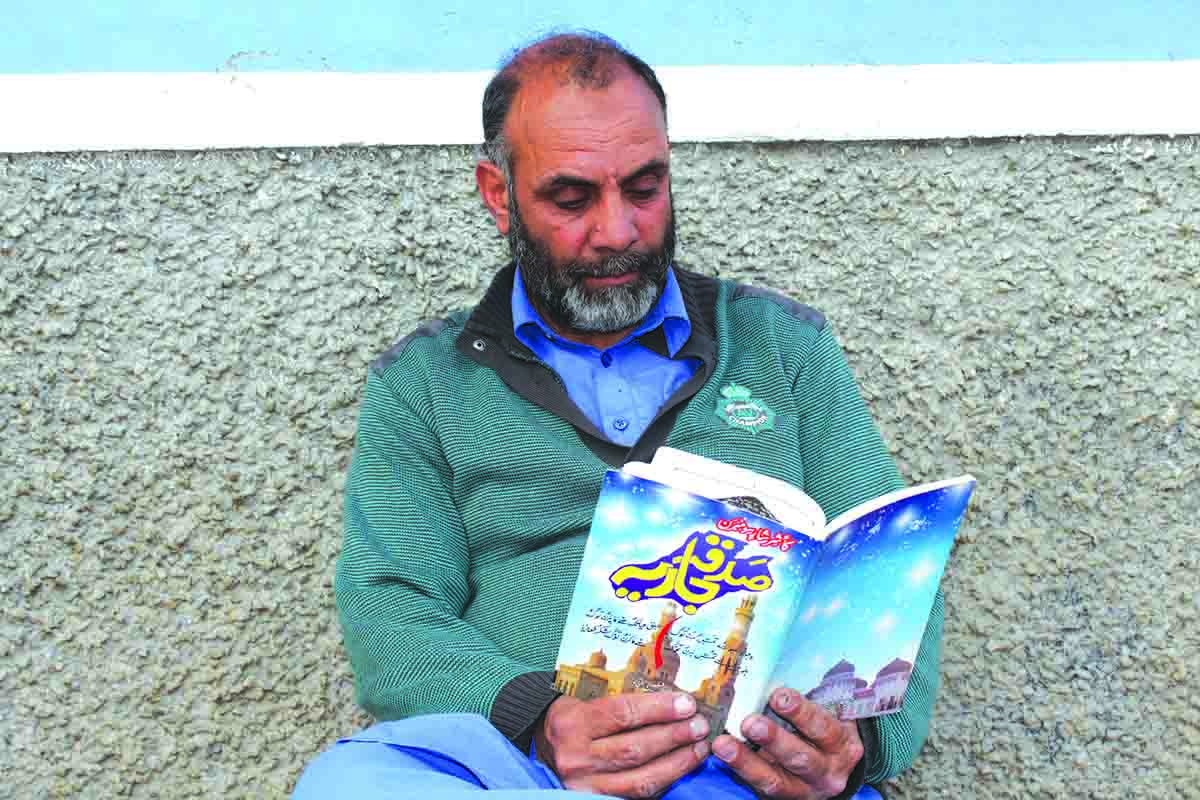

Poushgound (Bucket of Flowers) was his first poetic collection. When he wrote this, he was 14. His next collection was Sadq-aie-Jariyah (Ongoing Charity), which has an emphasis on being fearful to the might of God. His other books include Romut Anhaar (The lost Identity), Tyoth Teh Meuoth (Bitter and Sweet), Zakhmeach Zuag (The Pain of a Wound) and Fikre Hund Aalaw (A Voice of Concern).

In Romut Anhaar, Inqilabi says, addresses Kashmir:

Chuyya Mouloom Zuuv’as Chay Laar, Tche Gutch Beadaar Kashmi’rov

(Thee soul is hunted out, wake up, Oh Kashmir!)

Hewaan Chay Hea’th Woureh Mouja, Amis Namrood Sund Foujah

Che Na Chuie Kanh Seit Bouja, Choon Dag’eh Daar kashmi’rov

(Step Mother’s attrition is torturing you, with her inhuman military

You are a lone traveller of agony with no one to console you. Oh Kashmir!)

Dikh Na Nea’ab Jigar Txapus, Che Kaim Taqdeer Thowe Taapas

Mya Wantam Kar Yiye Wapas, Panun Anhaar Kashmi’rov.

(Just give me the whereabouts and I will gouge out his liver, who stole your fate. And tell me, when will you regain your lost identity, Oh Kashmir!)