The events of 2008, 2009 and 2010 exposed gen-next to a new Kashmir. They picked stones to vent their anger against a militrilized setup where men in uniform enjoy total impunity. Anando Bhakto talks to some of the youngsters who got exploited, physically, emotionally and financially in order to keep the narrative of peace alive

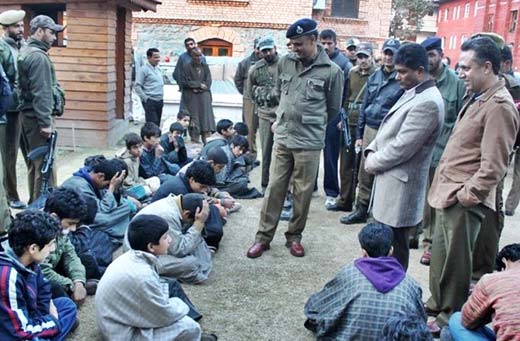

Pic: Shahid Tantray

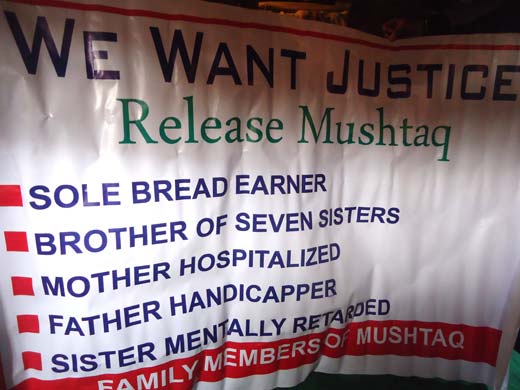

Fearing that once they had taken her brother to Kotbalwal in Jammu, hundreds of kilometres from Srinagar, she would not be able to see him again, Sameena came in front of the speeding police van at Zainakadal police station, trying to stop it. From inside the van, Mushtaq did not realise his sister had been pulled away before the vehicle rammed her over. He tried to force open the door, crying out his sister’s name in panic; crying out to God for help. And for such common human behaviour, Shabir, an associate of police, abused him, slapped him. And, began hitting him in the head repeatedly and mercilessly. A few hours later, Mushtaq resumed consciousness at Batmaloo police line with five stitches on his head and bruises all over his body. In the past 24 years, Kashmir and its people have learnt to live with what appears a never-to-end ‘oppression’. New Delhi too has learnt to pass this off as ‘democracy’!

Jammu and Kashmir is the only place where the Juvenile Justice Act of 1986 has not been implemented. The upper age limit of a juvenile has been fixed at 16 years, two years lesser than that mandated for children living in India. The consequences are enormous. “The Amarnath Shrine board controversy had led to massive protests in the summer of 2008. There were sit-ins, demonstrations, stone-pelting everywhere,” recalled Mushtaq Ahmed Sheikh, resident of Saidpora, Nawhatta in down town Srinagar. “One such day, a policeman came to our house saying ‘sahib’ had summoned me to Nawhatta Police Station. When I reached there, SSP Ashiq Hussain Bukhari demanded that I told him the names of five stone pelters. I was surprised. I knew none.”

What happened to Mushtaq thereafter, barely 13 then, is a ghastly account of how rule of law in Jammu and Kashmir is ‘abused, outwitted’, and more often than not ‘circumvented’ to suit the caprice of police personnel. “The SSP booked me under Public Safety Act (PSA); I was neither produced before any magistrate nor taken to court for hearing,” recounted Mushtaq. “Later when the court sent me to police remand, I thought I would be out once the remand ended in a couple of months. But the police had its tricks. Since only one remand can be issued for any one police station, they started shifting me from one police station to another and so on to get fresh remand orders at the end of the existing one.”

For the next one and a half years, Mushtaq was imprisoned in over half a dozen police stations including Safakadal, Zainakadal, Urdu Bazar, Rainawari, Khanyar and Maisuma police stations. This was in blatant deviation from the provisions of the Juvenile Justice Act which stipulates that no juvenile can be detained in police station or jail for a period longer than 24 hours, and that the juvenile must be sent back to their parents or guardians or to a juvenile home, if identified as neglected or delinquent juvenile.

Pic: Bilal Bahadur

The JJA provides that if a juvenile is produced before a court he must be granted bail then and there, subject to the issuance of a bail bond from his parent that he would not participate in unlawful activity in future. But the police in Jammu and Kashmir have developed a whole gamut of strategies to frustrate bail pleas. One, the police and the judges deny prima facie that the accused is a juvenile. Second, as in Mushtaq’s case, they shift the accused to a different police station once bail is issued. And third, after the accused is released, the police immediately book him under a different act. Mushtaq is an example. “After I was released in 2012, the police rearrested me three months later. I have no clues, why? A second PSA was slapped against me. I was first lodged in Urdu Bazar Police Station, then at Zainakadal Police Station. It was then that I was being taken to Kotbalwal, Jammu. But the head injuries done by Shabir, after my sister tried to stop the police van, ensured I stayed in Srinagar.”

In the three months when he was set out free, his hopes for reconciling to his formative years as an adolescent were already dead. His father’s health deteriorated noticeably, and his mother suffered major ailment related to gall bladder. The only brother in seven sisters, including a mentally retarded one, he preferred to work as conductor in a bus rather than study. At any rate, once a juvenile is detained for stone pelting or any other anti-state activity, it is next to impossible for him to continue studies. Said Faizan, a juvenile who was detained in Safakadal Police Station on charges of stone pelting and setting a Rakshak van on fire in August 2012: “The prejudice of teachers and my fellow class-mates was marked. They shunned me totally. I felt very odd when I went back to Shaheen Public School on my release. In a few days, I decided to quit school.” His parents have now planned that he should appear as a private candidate for matriculation examination when he turns 15 next year.

Advocate Babar Qadri, who has handled many cases of illegal detention and physical abuse of juveniles, said the police have a free hand in determining the fate of a juvenile prisoner. The police illegally detain juveniles without registration of FIRs, and that in many cases extend to months together. “In Kashmir, security concern overrides human rights and child rights like nowhere else. The Jail Manual followed in Jammu and Kashmir was last changed in 1957. It recommends a daily allowance of Rs 27 per day per head for prisoners and that covers all expenses including food. Can anybody imagine surviving on Rs 27 a day? Kashmiris are treated as fifth world citizens.”

Significantly, the actual problems for the juvenile detainees arise after they are released. Their names are listed in all the police stations and whenever there is anticipation of stone pelting or anti-state demonstration, or a ‘hartal’ by pro-freedom groups, these juveniles are summoned to police stations and detained till evening. “You become a problem for your family, neighbourhood, school and your friends. You have no career, no social life, no hope for future,” Qadri remarked. This also impacts employment opportunities very often. One of Qadri’s clients Bilal Ahmed Makhdoomi of Gojwara area in Srinagar was forced to earn bread for his family at the tender age of 16 in 2011, after his father suffered a sudden brain stroke, not able to bear the detention of his only son among six daughters. The Public Health Engineering Department under SRO 43 offered to induct him as staff as replacement for his dead father, but he lost this opportunity as the police did not issue him a No objection Certificate. One wonders, when the state exhausts all employment and material opportunities of a civilian, makes no effort to lift him from penury, helps him weave no dreams for a sustainable future, regresses his every hope into despair, how else does it expect him to react than pelt stones? But when he does pelt stones, the state responds with unspeakable coercion. During the consecutive summer hartals in 2008, 2009 and 2010, the state fired indiscriminately at protesting crowds, killing approximately 45, 32 and 122 civilians, respectively – majority of them juveniles!

The bailed juveniles, once they are out, are forced to work as police agents or collaborators. One of Qadri’s clients Danish Farooq, resident of Sajjadabad, Srinagar, was taken to various places during raid operations by police and forced to identify another juvenile Umar Farooq as fellow conspirator against the state in 2012. The accusations against Danish were shady. On 12 June 2012 a petrol bomb was hurled on G Convoy of CRPF’s 144 battalion. Whereas on the night of this incident the CRPF personnel lodged FIR against three unidentified persons (testifying that they had no clues of the perpetrators) at Kralkhod Police Station, Danish was made an accused later and then forced to identify Umar. The price of collaboration was heavy; angry neighbours of Umar attempted to set Danish’s house on fire the very next day.

“In my case, SHO Showkat’s car overtook my bus one fine afternoon while I was on board as conductor. Shamim, a resident of Gojwara, screamed out my name, pointing his finger towards me and saying Yahi hai, yahi hai (It’s him, it’s him). Before I could understand anything, I landed up in Nowhatta Police Station, where the police personnel kept asking me to identify stone pelters,” recounted Mushtaq. On his refusal to act as agent or ‘cat’, as collaborators are locally known, he was subjected to full night physical abuse and torture by Showkat and his associates. The impunity with which the police behave in J&K is indeed suggestive of a ‘Nazi rule’. In 2013, even as advocate Gowhar Makhdoomi approached SSP Aashiq Bukhari with bail orders from Lower Court, Srinagar, the police refused to release Mushtaq. He was sent to Kupwara jail, where he remained for the next four months until his release on January 1 this year. Advocate Shafqat Hussain has demanded a compensation of Rs 10 lakh for Mushtaq’s family for the illegal detention of their lone bread earner.

“There is a police state in Jammu and Kashmir for the past 24 years. The police do what they will. The courts are too helpless to take any action against them. Who do we approach here? It is a state where near one million armed forces have been stationed by the centre to contain a possible insurgency threat from merely 150 militants. When the state itself shows such evident discrimination, where is the hope for justice?” lamented Hussain. No wonder, when he raised objections at Mushtaq’s continued detention despite court ordering the latter’s release, a very senior police official remarked outrageously: “Court to hamara joota hai (the court is under our feet).”

Indeed, the courts appear helpless. Sometime ago the Jammu and Kashmir High Court dismissed a petition in the form of PIL demanding ban of pepper gas shelling and pellet guns. The court argued these were not harmful to the human body, although cases galore where people have lost their eye sight after being injured with pellets. “This was done under pressure from the Home Department, and was certainly in violation of every established norm of a judicial system,” alleged Qadri.

The Bar Association in Srinagar has been consistently demanding that prosecution should withdraw cases of stone pelting against juveniles as it threatens to seriously undermine their prospects of education and social well-being. “In 1990 many suspect-juveniles ended up becoming full time police informers or collaborators. The parents today want to send their wards outside the state to avoid the same happening to them. But the pending cases against them mean they have to be physically present here and appear in courts for hearing on regular intervals. This denies them the chance for a more secure, dignified life outside the state where they would not have to live with the stigma of having been detained. This gravely affects their rehabilitation process,” said Basheer Siddique, another lawyer fighting for juvenile justice.

The Juvenile Justice Act, 1986, introduced copious provisions for the rehabilitation of juveniles. The act states that a Juvenile home is one which is not a jail and “shall not only provide the juvenile with accommodation, maintenance and facilities for education, vocational training and rehabilitation, but also provide him with facilities for the development of his character and abilities, and give him necessary training for protecting himself against moral danger or exploitation and shall also perform such other functions as may be prescribed to ensure all round growth and development of his personality.” Kashmir, where the lone juvenile home came up in Harwan area in 2010 after over two thousand juveniles were booked under various charges of arson and stone pelting including PSA, is a place worse than jail. “I was incarcerated in solitary confinement in a cell in Harwan, where there was no electricity or lighting arrangement. I was terribly scared by the thought of ghosts and evil spirits. When I called out for help or cried, my voice would echo in the dark, giving an eerie feel,” said Faizan, who was booked under charges 307, 147, 148, 149, 52, 427, 435 of RPC for alleged involvement in stone pelting in Iddgah, Srinagar, on 20 August 2012. The official in Harwan made him wash car, clean toilets, and beat him with pre-heated leather belt. The first day he was given food, the next day he starved from morning to dusk before being bailed out to his parents. “Mooh pe bhi mukka maara (They punched me on the face also),” Faizan told me, opening his mouth to give me a glimpse of his broken front tooth.

At times, there have been murmurs relating to sexual abuse of child detainees. But the state machinery, in particular its coercive police force, has been able to stifle the murmurs rather swiftly. “There was once a case of 11 boys detained for stone pelting in Maharajganj Police Station, of whom four were juveniles. The lawyers objected to the single chargesheet filed against all 11, and demanded there be a separate chargesheet for the minors,” said Siddique. “The four juveniles complained in court that they had been made to sodomise each other in the police station. When the Government Medical College examined them under court orders, the possibility of sodomy was ruled out. In any case, the examination was done after a lapse of five to six days; it was next to impossible to determine sodomy. However, the medical report mentioned that bruises were found in the private parts of the children, which raised strong suspicion that the alleged sodomy indeed took place.” But the police was quick to convince the children to not pursue the case by agreeing to drop chargesheet against them. A smart barter, indeed!

In Danish’s case again, the 13 year old was lodged with adult criminals who attempted to sodomise him under instigation from police. Although his lawyer Babar Qadri brought this to the notice of the court, the court refused to entertain plea against the concerned police station. On the contrary, the police promptly nicknamed Danish as ‘Petrol’, in reminder to his alleged involvement in hurling petrol bomb on a CRPF convoy.

In 2009, Abdul Rashid Hanjura, a social activist filed a Public Interest Litigation (PIL) in 2009 in Srinagar High Court. The litigation which questioned why the state government had not been implementing the JJA despite it being passed in 1997, accused the government of being blind and neglectful of its basic constitutional obligation to protect the rights of the child. “The state government has failed to set-up homes and courts. Non-implementation of the act and conduct of proceedings at regular courts results in dwarfing of the development of the child, while exposing him to baneful influences, coarsening his conscience and alienating him from society.” Hanjura found support in the court which directed the state government on June 5, 2010 to implement the law.

The government did not. For, it clearly had different plans. Currently, it is considering legislation of the New Police Bill. The New Police Bill is an essential blueprint to exercise control on the entire populace. It guarantees wider powers to the police, including collection of personal information on demand, the authority to arrest a person without trial for six months if he fails to produce the sought information, and increased surveillance of people. Importantly, the police officials will always be considered ‘on duty’ which will make prosecution of erring policemen virtually impossible.

In recent years, Kashmir’s infamous detention camps of the 1990s have undergone a makeover. What once echoed of howls of pain now resonate of bird song and good music. Ministers have quickly taken them over, to enjoy the surrounding mountains and mirror still lakes. The narrative of ‘occupation’ is changing. Through instruments such as the proposed police bill, the state will ensure Mushtaq and Faizan and ‘Petrol’ and thousands of other juveniles are filled with more fear. More trauma. More ridicule. More everyday ‘repression’. So that there is absolutely no note of complaint. So that there is no endeavour for justice. So that, there is ‘peace’.

Anando Bhakto, a New Delhi based journalist reporting on democracy and governance issues, is an alumnus of Asian College of Journalism. He has authored four all-India cover stories, and interviewed important political dignitaries on matters of policy concern. In 2013, he did MA in Journalism from Cardiff University. He contributed this story to Kashmir Life.