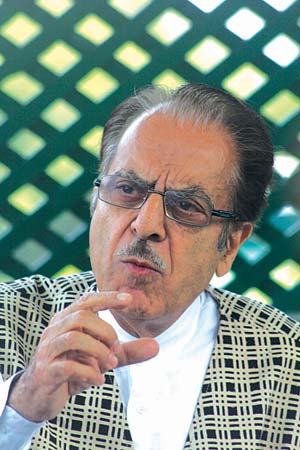

Academic Prof Saifuddin Soz has been in politics for a long time. Basically, from NC, he joined Congress and became a central minister. A widely travelled man, he led the state Congress also. Last week, his book Kashmir: Glimpse of History And The Story of Struggle was published by Rupa. Here we republish a brief excerpt from the book that explains Soz’s ideas about how Kashmir can see light at the end of the tunnel

I have lived through the years of turmoil in Kashmir, always considering myself to be part of the life of Kashmiris. I had got elected to the Lok Sabha in a by-election in June 1983 and since then I invested time to understand the life and times of Kashmiris.

India and Pakistan have never come to an agreement on Kashmir. It has also remained a live situation as an item on the agenda of the United Nations. Strangely enough, all the three basic stakeholders to the dispute—India, Pakistan and the people of Kashmir—have, by now, become absolutely disillusioned with the UN for a different set of reasons.

In my opinion, it is futile to look to the UN for any workable help for the resolution of the dispute as the powers holding the authority of veto have all along responded to the situations keeping their own strategic interests in view. It is why the whole world, seemingly in one voice, offers one simple advice, ‘Let India and Pakistan sort out the dispute bilaterally.’

My quest for a possible solution has led me to suggest the following.

- The primary responsibility goes to the Government of India, which must take steps to help the people of Kashmir to move out of the tormenting cycle of violence. The initial steps could be to show a gesture of compassion for creating a situation of relief in the minds of Kashmiris, who have suffered immense miseries from the very day the central government started dragging its feet from its commitments to willingly accept the decisions of the Jammu & Kashmir Constituent Assembly and the provisions of autonomy guaranteed under the Delhi Agreement of 1952.

Apart from the commitments of the Indian government at various points of time, the clear commitment made by the then prime minister of India, P.V. Narasimha Rao should serve as a guiding principle to take measures to resolve the dispute.

The first step in this direction could be to initiate a dialogue with the primary stakeholder, the people of Kashmir. And, if the Union of India has to talk to the people of Kashmir, it will have to decide the grouping with which it will initiate the dialogue. In my opinion, it is the political conglomerate called the Hurriyat. Then, the ball will certainly move to what is broadly known as the ‘mainstream’. Under the present circumstances, it is possible that ultimately the Hurriyat and the mainstream might have to move to a broader political consensus on an ‘achievable goal’.

- The Government of India should have realized much earlier that it was wrong for it to dilute the autonomy that was enshrined in Article 370 of the Constitution of India and the Delhi Agreement of 1952 between Nehru and the Sheikh. The Centre committed mistakes subsequently also by taking recourse to issuing orders unlawfully like the presidential order of 1954. It repeated another blunder by dismissing the Farooq Abdullah government unconstitutionally on 2 July 1984.

It committed yet another grave mistake by appointing Jagmohan Malhotra as the governor of Jammu & Kashmir for the second time on 19 January 1990, against the protest by the Farooq Abdullah government. It is widely believed that Jagmohan was squarely held responsible by the people of Kashmir for creating a chaotic situation of death and destruction in the state and also organizing the exodus of Kashmiri Pandits. So, it is the Union of India that caused unrest in the minds of the people of Kashmir and deepened it over a period of time by committing mistakes one after the other. The Union of India has to adopt a mechanism to assess properly as to what has gone wrong and how it can be corrected.

- The Government of India should implement a policy shift in Kashmir. The basic tenet of that would be the realization that no amount of repression in Kashmir, be it through bullets or pellets, can solve the problem. The anger in the minds of the people of Kashmir, particularly in the minds of the youth, has to be addressed. The policy shift will also envisage that the army, the paramilitary forces and the Jammu & Kashmir Police have to design a policy to win back people for a dignified and peaceful normal life.

- The Government of India should realize that the people of Kashmir have suffered enormously in the period of turmoil, spanning nearly three decades. The government itself admitted that more than 45,000 people have been killed in the crossfire in Kashmir during the past three decades. The people put that figure to be more than 70,000. This and other areas of suffering of the people in the crossfire during a long period of turmoil must be probed by a commission of inquiry. This way, the Government of India would bring great relief to the people of Kashmir, and it will constitute a substantial move towards removing the deficit in trust between the Union of India and the people of Kashmir.

- The current crisis might require the mainstream political class of the Indian state and the separatists represented by the Hurriyat to come to a common understanding for the settlement of the Kashmir dispute, so that the society moves to a ‘possible goal’.

- While this approach gains momentum, the Union of India could help to organize an internal dialogue among the people in the three regions—Jammu, Kashmir and Ladakh—and within a region, among the people of sub-regions like Kargil and Ladakh regions or/and Chenab valley and Pir Panchal, so that democracy permeates into the entire area of political, social and economic development on the basis of equity and justice. There are areas of public concern on which Kashmir and Jammu vehemently differ with one another. A vigorous dialogue alone can remove differences in approach and the Union of India can play a big role in this.

- The Union of India will have to consider that the presence of the army and paramilitary forces in Kashmir and elsewhere in the state is not needed in this magnitude. So, call it demilitarization or give it another name, something must happen in that direction so that a situation of peace and relief is caused in the minds of the suffering people.

- The Armed Forces (Special Powers) Acts (AFPSA) is draconian and has been misused in Kashmir. Even the army has accepted that the law has been misused on a number of occasions and has apologized. Its revocation will bring a great physical and psychological relief to the people of Kashmir.

- The people around control line and international border between India and Pakistan have suffered immense miseries, throughout the border in the J&K state. It is often that people around this line on the border have to move to the hinterland for long spells of time, due to shelling and crossfire. The Indian government should also think of providing insurance cover to the entire population on the border, say within the radius of five kilometres or more.

- Since our neighbourhood can’t be changed and India and Pakistan can’t live in perpetual animosity, the Union of India has to accept that it has to organize a dialogue on two axes—New Delhi-Srinagar/Jammu axis and New Delhi-Islamabad axis. I accept that proposition as a compulsion woven into the situation, that is, the Kashmir dispute.

While I have explained my outline on how to move forward, I want to take the position that Kashmir is not a complex problem but a simple proposition. It can be resolved if the leadership shows political sagacity and the resolve to find a solution.

While I have explained my outline on how to move forward, I want to take the position that Kashmir is not a complex problem but a simple proposition. It can be resolved if the leadership shows political sagacity and the resolve to find a solution.

One could see that the current unrest in Kashmir is a writing on the wall, and the stakeholders should respond to the situation and come forward for a possible solution.

The so-called Musharraf-Vajpayee-Manmohan formula envisaged same borders but free movement across the region—the erstwhile Jammu & Kashmir state, Gilgit-Baltistan, Pakistan-held Kashmir, Kashmir Valley, Jammu and Ladakh; autonomy on both sides; demilitarization, that is, phased withdrawal of troops from the region and a mechanism devised jointly so that the roadmap for a settlement is implemented smoothly.

As per credible sources, General Musharraf had convinced his top colleagues, both in the army and outside, that this was the only possible solution that would not yield a situation on the ground as a defeat for one party and a victory for the other. He had also convinced his colleagues that the resolutions of the UN on Kashmir had constituted a redundant situation as these meant a tight-jacket for Kashmiris whether they wanted to go with India or to Pakistan. Musharraf had explained that if Kashmiris were given a chance to exercise their free will, they would prefer to be independent. In fact, this assessment of Musharraf seems to be correct even today!

One word about the proposition for making borders irrelevant. When irrelevance of borders is offered within the so-called formula, an effective mechanism of safeguards would also be in shape so that the settlement of dispute won’t cause any difficulty in respect of sovereignty and security of India and Pakistan.

If the leadership of India and Pakistan are prepared to realize that the neighbourhood can’t be altered and war won’t now be a possibility, then the future of an abiding friendship and cordiality for peace and prosperity for the people of both countries has to be sought at all costs.

We must not forget that after the Lahore Declaration, there were serious attempts to promote an atmosphere of hope and optimism between India and Pakistan. Knowledgeable sources suggest that the idea of reconciliation between India and Pakistan was mooted by President Musharraf in his summit with Prime Minister Vajpayee in Agra on 14-16 July 2001. After the Kargil war, which didn’t yield any advantage to Pakistan, Musharraf seems to have a calm reflection of what could be done for the future as for the Indo-Pak relations and the future of Kashmir dispute was concerned. Musharraf has realized that Pakistan would never gain anything through the war with India.

In June 2007, when I was a minister in the Cabinet, Prime Minister Manmohan Singh had invited me for a discussion on Kashmir. I found him unusually optimistic on Kashmir’s solution. He shared with me that he would visit Islamabad next month to have a decisive dialogue with Musharraf—much to my relief. After two weeks when I attended a Cabinet meeting, perhaps in the second week of July 2007, I followed the PM to his chamber after the meeting and enquired as to what had happened to his visit to Islamabad. He told me that it was Musharraf who requested him for postponement of the crucial meeting and he would fix the date soon. That was unfortunate as that time never came till Musharraf was out of the system for a different role in public life!

It was unfortunate that Manmohan Singh could not fulfil his mission and his travel to Islamabad for the final and decisive meeting with Musharraf sometime later in July 2007 could not take place because Pakistan’s internal security got vitiated by unfortunate events like Musharraf’s avoidable dispute with the judiciary of Pakistan and the siege of Lal Masjid (3-11 July 2007) causing violence and unrest all around.