Eight reporters and lensmen travelled more than 5,000 km across remote belts in Ladakh, Kashmir and Jammu for 15 days to cover 24 powerhouses. Backed by a team of researchers, designers and editors, it created a document – a historic first. Enjoy the read.

A Restart, A Century Later

With a major project in operation, a new policy in hand and improved expertise and knowledge in managing and maintaining the assets, the J&K government is keen to undo the losses the state suffered in its recent history. R S GULL gives a peephole view of the thinking at the state’s energy desks

For most of the recent past, Kashmir was all about handicrafts, the Cashmere, as the Pashmina wool is still referred to in the West. However, some of these arts perished because of the lack of cheap power.

It was at the beginning of the twentieth century that Srinagar durbar commissioned a micro hydropower project. But the artisan was struggling, much earlier, to see if any mechanical intervention could help reduce the costs, increase the yield and improve the margins. Records suggest the artisans were not a failure altogether. There is historical evidence suggesting that Kashmir used mechanical power in bigger handicraft workshops where looms would operate with the help of hydraulic power – the water mills.

Charles Elison Bates and Walter Lawrence who visited Kashmir in the early 19th century, observed that a lever mill used in the manufacture of famous paper, the Kashur Kagaz, worked with water power. Traditionally the lever mills operated by water power or animal power were called jindrah muhul.

In 1877, the availability of hydraulic power at Ragunathpora near Naseem Bagh was responsible for setting up some units of the newly organized silk industry. Of the 470 reels, 92 were turned by waterpower and the rest manually. Steam heating with the help of wood charcoal, which many industrialised countries across the world were using much earlier, was introduced in some filatures of the silk industry in 1918.

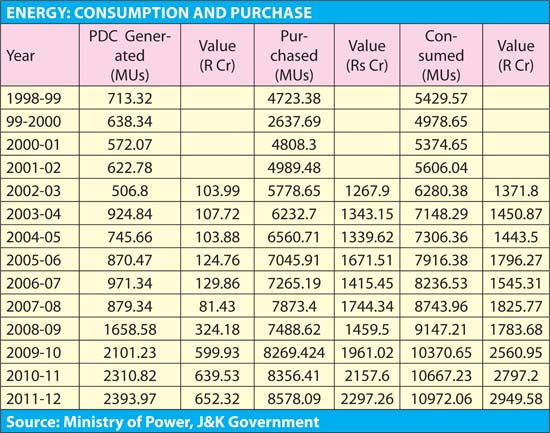

Despite having so strong foundations for an urge to get ‘empowered’ for healthy survival and progress, J&K is still considered one of the many backward states in India. Generally, the overall backwardness is attributed to its enormous energy deficit. A water-abundant state that literally piloted harnessing of water resources for clean energy at the beginning of the twentieth century is dependent on massive imports 100 years later.

Despite having so strong foundations for an urge to get ‘empowered’ for healthy survival and progress, J&K is still considered one of the many backward states in India. Generally, the overall backwardness is attributed to its enormous energy deficit. A water-abundant state that literally piloted harnessing of water resources for clean energy at the beginning of the twentieth century is dependent on massive imports 100 years later.

After decades of slumber, this issue is nowadays dominating the public discourse in the state. It is at the core of the new narrative that is written and discussed from Srinagar to Jammu. For the state government, it is the energy that stands flagged as a top priority issue. Emphasis on energy in policy-making is not only dictated by the massive fund requirements that go into the energy purchase year after year, upsetting the overall public finances. The desperation of the people to have round-the-clock supplies, especially during harsh winters in Kashmir and the hot, humid summers of Jammu is another factor. The larger reality is that the water not harvested in time is a gone commodity, especially in Kashmir which is gradually emerging as the new crucible of climatic change. The water level of almost all the major rivers across the state has shown a marked fall if compared to the 1940s and ‘50s.

Given the geography of the state, J&K is not fully linked to a grid within the state. Most of the valley and Jammu are linked with the Northern Grid but the arid Ladakh desert is insulated from the rest of the state by Zoji La. So is Gurez, Machil and Keran. This has added to the costs as people are getting electricity for some fixed time from diesel generators, which is very costly energy.

Leh has 59 units of Diesel Generator sets at 49 spots with a cumulative installed capacity of 19537 KVA. Kargil has 58 units at 39 spots with 16425 KVA capacity. Gurez has 19 DG sets at 18 spots with 2882.5 KVA capacity. Machil and Keran have one DG set each, generating 320 KVA energy.

Leh has 59 units of Diesel Generator sets at 49 spots with a cumulative installed capacity of 19537 KVA. Kargil has 58 units at 39 spots with 16425 KVA capacity. Gurez has 19 DG sets at 18 spots with 2882.5 KVA capacity. Machil and Keran have one DG set each, generating 320 KVA energy.

It affects the local ecosystem and atmosphere adversely and costs dear to the public exchequer. Within a year or two, this problem is expected to be over in most of Ladakh but the status quo will prevail in the rest of the inaccessible belts across the state.

The energy crisis in the state is an outcome of multiple factors. For most of the last century, a set of issues dominated the energy scene. From the October afternoon of 1947 when tribal raiders vandalized the wooden flume of the Mohra powerhouse to the mysterious blasting of some power transmission towers in November 2002, there are countless instances suggesting the energy sector cannot remain immune to the happenings at a place that has remained politically unstable.

The partition of the subcontinent that violently divided J&K was followed, many years later, by a water-sharing treaty that gave rights over the waters of the state to Pakistan. The Indus Water Treaty has remained and will continue to be a major challenge for the state government to harness the potential of its water. Prolonged negotiations on every new water-related project have created a psychological barrier.

The successive governments did try their level best to utilize the peaceful patches of history in creating certain assets. These piecemeal investments staggered over years in a closed economy did help create small projects which continued to be the main bread and butter of the state till the flagship Baglihar project was commissioned a few years back.

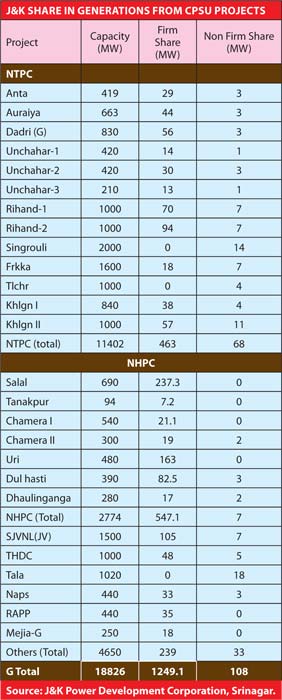

Access to capital could have helped manage the situation better but the non-availability of counter-guarantees for attracting foreign investment in the state’s energy sector was a huge setback. This eventually helped the central public sector undertaking, the NHPC to become the principal harvester of water resources with the state government playing second fiddle. The federal investments took place in such an insulated fashion that the state government had to literally reinvent the wheel to understand how major energy projects are executed and managed!

But the situation is changing. The creditworthiness of the J&K State Power Development Corporation (PDC) is up, especially because it has not defaulted even on a single penny. Baglihar generations are a continuous money machine that offers an investor confidence. PDC is capable of managing any major project – both in its implementation part as well as the management of the asset. Right now Baglihar is managed by the PDC engineers. Engineers at various levels – investigation, designing, drafting, dispute resolution (an engineer was always part of India’s negotiations process with Pakistan during the dispute resolution on Baglihar), financing and fault finding, have demonstrated excellence in the last many years.

And finally, there is a policy in place. Apart from the ongoing process of redefining its relationship with the NHPC, and seeking compensation from the centre for the Indus Water Treaty losses, the J&K government has a clear idea of what it intends to do and how. It is going to be a multi-phased, multilateral approach to managing the state’s energy deficit. A separate policy for small projects to be implemented by independent power developers, mega projects to be managed by major companies, a joint venture system and finally an emphasis on how the PDC should implement various energy projects on various tributaries of major rivers of the state. It is already working on some major projects including the second phase of Baglihar, Parnai in Poonch, Lower Karnai in Kishtwar and the new Ganderbal.

This special publication is taking care of the generation side of the story, tackling the evolution, the crisis and the assets. Transmission and distribution, the two other critical parts of the larger energy story need detailed coverage that Kashmir Life will attempt in future.