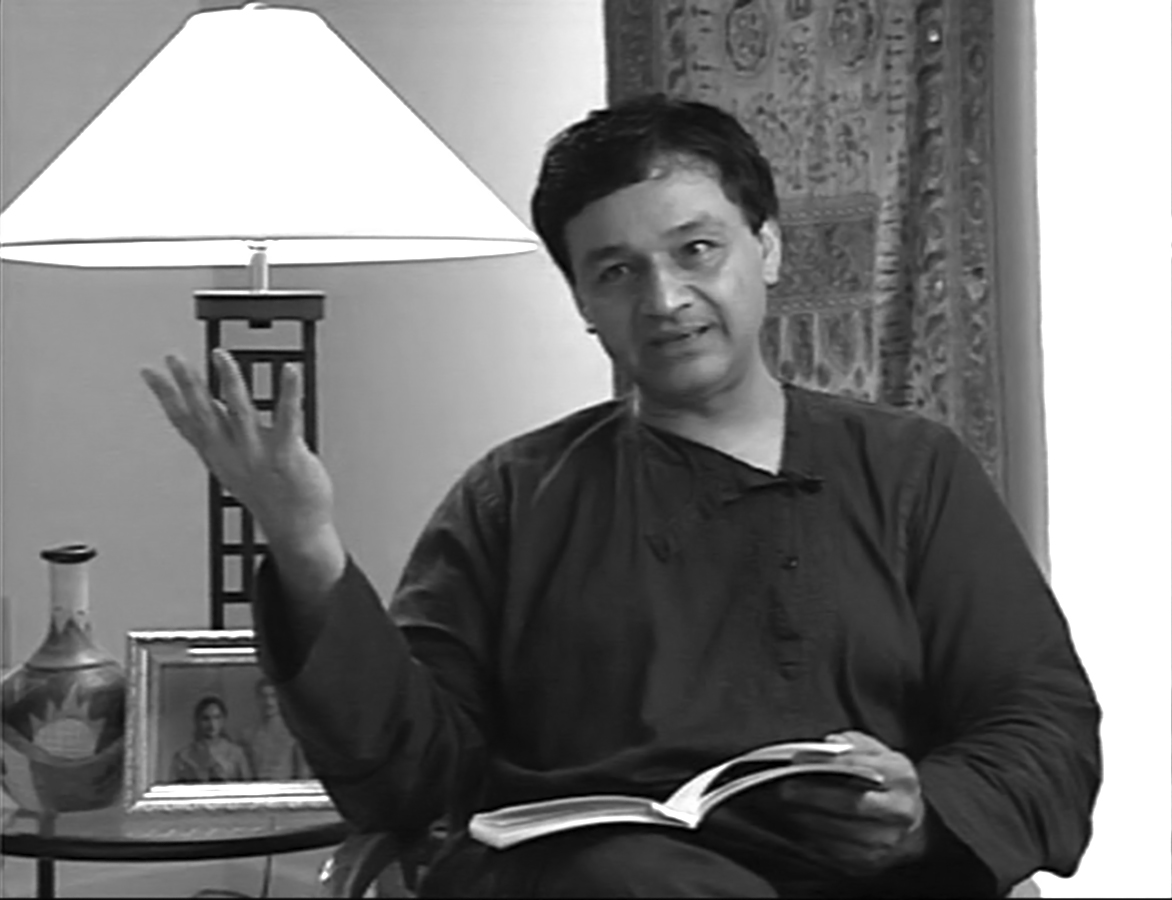

by Prof Suvir Kaul

I do not know why Shahid—Bhaiya, as we knew him—chose to address to me “A Pastoral,” one of his poems of loss, longing, and imagined redemption, but I am deeply grateful that he did so. I remember his phone call when he asked if I would mind if he dedicated one of his poems to me, and I said yes of course, not only would I not mind I would be very thrilled! But I hadn’t seen the poem then, and saw it only much later, and much later still understood why Bhaiya might have thought of me as he wrote, or once he finished, his poem. The poem is, in the most profound sense, an invitation and a deferred promise:

We shall meet again, in Srinagar,

By the gates of the Villa of Peace,

our hands blossoming into fists

till the soldiers return the keys

and disappear. Again we’ll enter

our last world, the first that vanished

in our absence from the broken city.

Once again: why me? I was far from the only Kashmiri Pandit friend Shahid had, and I can see that it is right, and just, that this poem should invite, into the act of return and restoration, a Pandit, but there were so many others who might suit that purpose. He and I had talked about poetry and politics of course, but he must have done that with others, and I now wonder if he had noted the fact that conversation about ideas and writing and history was what had linked our lives in Srinagar, where I first met him, then Delhi, where he taught and I was a student, and then in the United States, where we completed doctoral degrees and found jobs in different universities. In any case, I will never know the answer, but I do know that I am only, over time, beginning to understand that Shahid’s invitation was also a demand, a gift of shared responsibility.

I have thought often of the deeply ironic title of the poem: once, Kashmir could only be found in pastoral poetry and art, which dematerialized human lives and social contradictions into the rustling of brooks and the lapping edges of lakes, the green carpets of meadows, the orderly lines of flowers in well-laid gardens, the tall trees of the hills and the snows of the high mountains, and the unchanging timelessness of a land outside history. In contrast, in Shahid’s poem Srinagar is a city of blight and blood, and requires humane, therapeutic action: “We’ll tear our shirts for tourniquets/ and bind the open thorns, warm the ivy/into roses.” There is no flowering garden here, for the gardener now lives only as a voice that confirms rumours of the occasion of his death: “It’s true, my death, at the mosque entrance,/in the massacre, when the Call to Prayer/opened the floodgates.” This is a city of search posts and of cemeteries with “hurried graves/with no names.” Even spring brings with it not renewal but a new and astonishing herald: “the mountain falcon” that rips open, “in mid-air, the blue magpie,” and carries it limp from its talons.

Once home, what do we find but—and this is a recurrent theme in Shahid’s poetry—lost letters. Or rather, letters that have been delivered in the absence of the addressee, for the mailman was sure “we’d return to answer them.” When these not quite dead letters speak, they echo the “plaintive cry” uttered first by the bird:

See how your world has cracked.

Why aren’t you here? Where are you? Come back.

Is history deaf there, across the oceans?

But now we are home, the poem says, our keys are opening locks, and we walk past dusty mirrors and light lamps and view dimly “The glass map of our country.” There are pictures on the staircases as we climb up, and they are of our ancestors, and they too speak:

Their wish

was we return—forever!—and inherit (Quick, the bird

will say) that to which we belong, not like this—

to get news of our death after the worlds.

Not long after Shahid died a decade ago now, I did return to Srinagar and found the city he mourns so poignantly in “A Pastoral” and the other poems of The Country Without a Post Office. We did dust the rooms and pictures in our ancestral home and were glad that those who gazed down at us had not lived to experience the ravages of the last two decades. They would not know or understand this Kashmir, with its murderous history and its terrible schisms between populations and families. What I saw then moved me to write about Kashmir, and I continue to do so, if only to understand for myself all that turned Kashmir, and Srinagar, into the armed camp it continues to be. And I think Shahid’s invitation knew, well before the fact, that such a moment must come, which is why “A Pastoral” is also a promise of a future of rediscovery and renewal, a future without soldiers, a future of shared hopes and lives.

And Shahid, who is no more, does he keep his promise to return, to renew, to heal? Of course he does, for no one knew better than he did the power of words, of the speaking voice, of poetry as the pulse of life beyond death. I hear his voice still, and I know, as the years pass, Kashmiris (and not only Kashmiris) hear in his poems their passion, their loss, their anger, their determination, and their aspiration. And in their many voices, as they read and celebrate Shahid, I hear the future to which he, so beloved of many, bore powerful witness.

(Suvir Kaul is A. M. Rosenthal Professor of English, University of Pennsylvania)