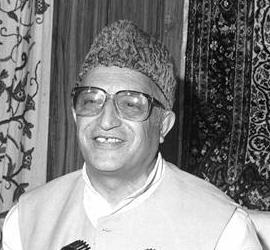

by Mohammad Sayeed Malik

There is no doubt that Indira Gandhi, having lost faith in Farooq, took advantage of odd events on the ground and set in motion the process to make ‘July 2, 1984’ happen.

Her task was made easier by Farooq letting grass grow under his own feet.

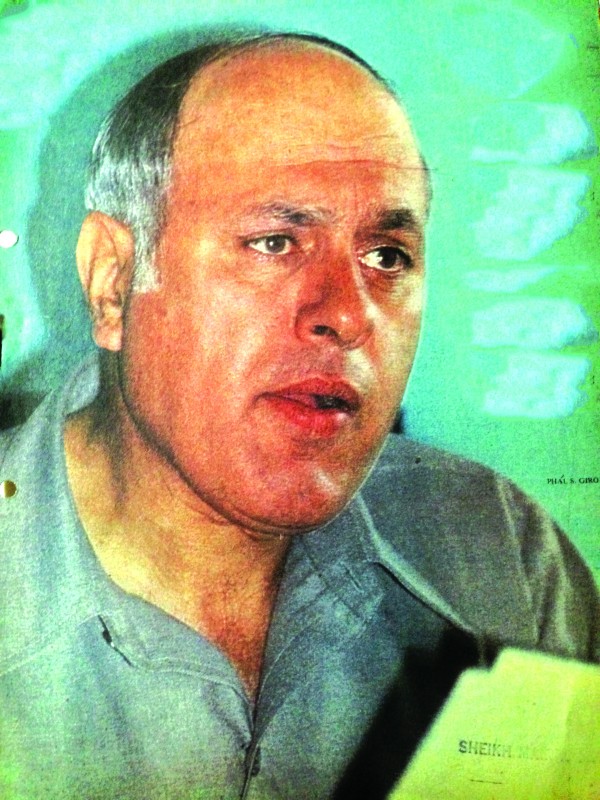

Like everything else about Kashmir, truth has many versions of who, why and how of ‘July 2, 1984’ when GM Shah dislodged Farooq Abdullah from power.

Immediately after its occurrence the event used to be celebrated as ‘day of deliverance’ by the gainers and mourned as ‘black day’ by the dispossessed. Even today, there are unanswered questions in the conflicting narratives in circulation.

For example, if the Congress and the dissident (‘defector’) legislators were to be exclusively blamed for alleged subterfuge and ‘backstabbing’ (father) how is it that the son (Omar), as well as the father, is today so comfortable with some of the very same bedfellows?

As against this, GM Shah’s comparative unpopularity on the ground did not deter him nor come in his way to say ‘no’ to power-sharing with Congress on whose life support system his regime survived. He opted for terminating his short lived, but generally acknowledged as better-administered tenure, on this bitter note.

Similarly, if, as is claimed, the ‘July 2,’84’, was an ‘ambush’ against popular aspirations in the Valley then why did Farooq Abdullah have to resort to reckless rigging in the very next (1987) assembly polls that, in turn, provided the trigger for armed insurgency? And why has the National Conference been losing, not gaining, in successive assembly elections since 1984?

Elections in 1996 were farcical.

The post-Sheikh leadership is evidently out of sync with genuine popular aspirations.

The drooping graph of the party’s popularity and stature since 1984 is largely rooted in post-1982 leadership deficiencies. Precisely, that was the root cause, though not the only reason, for open break in the dynasty within two years of the death of its unrivalled patriarch in September, 1982. Simmering discontent in the rank and file fuelled by latent rivalries between competing contenders reached their flashpoint with Begum Khalida Shah assuming the leadership of what is today the Awami National Conference. Farooq’s superficial style of functioning, coupled with palpable backstage manipulation, made it easier for his rivals. To nobody’s surprise but his own, Farooq found himself dethroned one fine morning—July 2, 1984.

It is safer to rely on archival material than on eye-witness account because so many supposed witnesses invent things. The actual event was preceded by cloak-and-dagger succession struggle, behind the scene, as Sheikh Abdullah’s health deteriorated. In his book, My Dismissal, Farooq Abdullah acknowledges that his hasty midnight installation as chief minister, before Sheikh’s burial, ‘had the approval of Indira Gandhi’. The late DD Thakur’s key role (for Farooq and against GM Shah) in the palace intrigue (over succession) is also acknowledged. Farooq’s account of why Indira Gandhi and Thakur turned against him soon after and ‘conspired’ to oust him has too many holes.

Two governors, BK Nehru and Jagmohan, have recorded diametrically opposed versions of what led to Farooq’s downfall. But both agree on their assessment of Farooq’s flawed style of functioning and accuse him of ‘unreliability.’

Citing an instance of breach of his trust, BK Nehru in his autobiography, Nice Guys Finish Second, recalls how Farooq manoeuvred a confidence vote on the floor of the state assembly in defiance of his commitment to the governor who was known to be supportive of Farooq and had rebuffed Congress high command on that score.

Soon after chief minister, Farooq Abdullah got that ill-advised confidence vote passed in the Legislative Assembly Governor BK Nehru retaliated with a terse communication to him, warning him that his over-smartness was fraught with ‘serious implications’. It did not take too long for Nehru’s dark prediction to materialise, though by then Nehru had been shifted out from J&K.

Nehru’s successor in Rajbhavan, Jagmohan’s version of the July 2, 1984 developments, though claimed to be based on facts, betrays his prejudice against the Abdullah dynasty in general and Farooq in particular. However, even his biased account contained in his book, My Frozen Turbulence in Kashmir, cites documented evidence of Farooq’s politico-administrative waywardness.

There is no doubt that Indira Gandhi, having lost faith in Farooq, took advantage of odd events on the ground and set in motion the process to make ‘July 2, 1984’ happen.

Her task was made easier by Farooq letting grass grow under his own feet. Also, Farooq, probably just once in his life time, contracted megalomania. He forgot the crucial difference between being his father’s successor and not his replacement. Sheikh’s successor started acting like Sheikh, forgetting that he had not earned the crown on merit but owed his out-of-turn succession to Indira Gandhi’s decisive partisan intervention against GM Shah.

Farooq’s inflated ego drove him into the ‘wrong company’. He did something that his father in his wisdom had avoided like plague: active involvement with national opposition. Adventurism replaced Sheikh’s safe formula of remaining on a ‘common wavelength’ with the party in power in Delhi.

Forgiveness was not among Indira Gandhi’s virtues. Farooq did not have the ability or experience to survive an unequal combat. His foes struck just when he was taken in by his larger than life image on the national scene while his own home-ground was slipping from under his feet.

Lingering discontent over succession started eating into the vitals of both, his government and his party. Farooq’s flamboyance blinded his vision. He had no inkling of the grass growing under his feet. Dissatisfaction among his ministers, legislators and party workers did not bother him.

It took the ‘motivators’ six to eight months to sniff and net the dissenters. As soon as the target figure, 13 MLAs, was reached the rivals went for the kill.

Farooq’s own account betrays his ignorance about happenings in his backyard. He, his political colleagues and his apparatus emerge as having been clueless. Even long after the event, probably to this day Farooq does not seem to know the vital fact of where exactly the rebel legislators had assembled on that fateful night between July 1 and 2. Their hideout was a prominent politician’s roadside residential house in cantonment area and not the Forest Galli residence of Iqbal (‘diathane‘) Bukhari, as mistakenly believed by him.

The defector legislators travelled the short distance from cantonment to Rajbhavan in a caravan of cars, via Gupkar Road, shortly after midnight. The caravan moved along the outer wall of Farooq’s residence where he was in blissful sleep in those momentous wee hours of July 2.

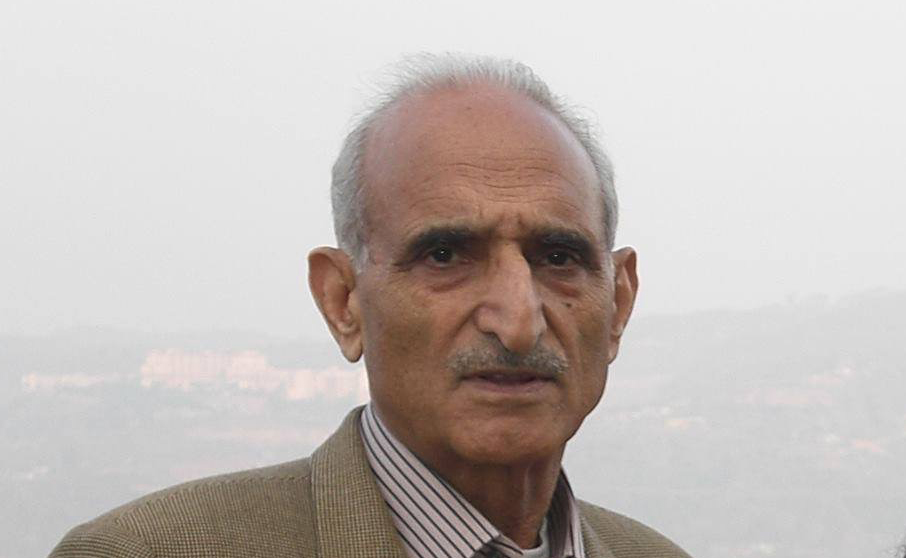

When Abdul Ghani Lone called Farooq early that morning to convey that his horses had bolted, he laughed it away as ‘one of those usual daily rumours’. It was only when he was called to the Rajbhavan around 7.30 am that the crushing reality dawned upon him. But it was too late by then and, according to Jagmohan, Farooq pleaded for imposition of governor’s rule rather than crowning ‘that scoundrel’ (Shah). This suggestion tickled Jagmohan’s own latent ambition but he had to behave and was commanded to obey. Farooq’s written ‘advice’ to the governor three hours later (demanding floor test) was, in effect, only a belated second thought instilled by PL Handoo and Mohammad Shafi (Uri). But by then Farooq’s goose had been cooked. He had readily conceded defeat earlier when confronted with the reality by a none-too-friendly Jagmohan and, in desperation, pleaded for governor’s rule.

His dream of double crossing both Farooq and Shah shot down by New Delhi, a sullen Jagmohan reluctantly administered oath to GM Shah and his team, including each one of the thirteen NC rebels, at the fag end of a long day.

Legislative calculus had been meticulously worked out by the Congress to just cross the halfway mark (to bare minimum majority) on the Assembly floor.

The D-day appeared to have been carefully selected. 2nd July, 1984 happened to be the second day after Eid-ul-Fitr which is when everyone in Kashmir is in festive mood, officialdom being no exception.

A senior colleague of Farooq recalled that though they smelled something fishy in the air but a coincident occurrence put them off-trail: Mufti Mohammad Sayeed had distributed invitation cards for his daughter Mehbooba’s July 5, wedding. At the cabinet’s pre-Eid meeting they discussed ‘rumours about defection’ but apparently were taken in by the timing of wedding in the Mufti house.

They dispersed for Eid holidays self-assured that Mufti must have set the wedding date after ascertaining that nearly week-long wedding celebrations passed uninterrupted. In fact the invitation card was closely examined, at the cabinet meeting, over the date issue.

In the end, not only did the Farooq camp pay for its fatal miscalculation but even Mufti household had to grudgingly curtail their celebrations as curfew followed Farooq’s overthrow on the second day of Eid.

Although these facts suggest that Mufti may not have had exact fore-knowledge about the D-day, Farooq’s version is that Mufti not only knew the (2nd July) date but that he also spilled beans in his speech at Jammu a couple of weeks earlier when he cryptically told a Congress gathering that ‘better days are around the corner’.

Whether the Congressmen took Mufti’s alleged ‘hint’ or not, Farooq must still be cursing his own failure to grasp it. The end result was that Farooq lost his inherited political self-sufficiency, eventually passing a crippled, truncated legacy to Omar Abdullah.

34 years after that fateful event on July 2, 1984, the legacy has shrunk beyond recognition, apparently irreversibly. Today the atrophied NC looks like a pale image of its old self. Its ability to regain its political supremacy, more importantly legislative self-sufficiency is in serious doubt.

That objective seems too daunting, in the vastly changed political terrain, even with Farooq Abdullah still rated as the tallest in the (mainstream) field. And Omar’s capability as well as ability to regain their old glory remains untested.

Until and unless that objective is achieved the NC is destined to suffer the lingering consequences of ‘July 2 (1984)’ infliction.

(A former editor, Malik is a senior commentator who has reported the coup. The article appeared first in The Kashmir Times and is being reproduced with permission.)