Artist Veer Munshi’s world starts and ends with Kashmir, his roots, migration and the crisis in between. Last week, his efforts led to a major art exhibition in Srinagar that was attended by an impressive number of non-resident migrant Kashmiri artists. Bilal Handoo had written this piece a few years back and was parked for an appropriate occasion for the publication that Concourse finally bestowed

Ever since he abandoned his home in a historic huff of early nineties, Veer Munshi has been visiting his homeland as an art pilgrim. He often stops by the clock tower in Srinagar’s Lal Chowk to revisit the ‘good old days’, when he was traversing those lanes as a budding artist.

Then, he had newly started a magazine and was looking forward to create a name for himself in Sun City, before the political storm sent him packing to plains. Like his creative initiative, he forever lost his “love of his life” in the mountains, he calls home.

Today, those musings are part of yesteryears’ delight for this Barbarshah native, who rose to become a world-class artist, away from home.

“But I keep returning to this city where I’ve stacks of memory,” Munshi says, warily gawking the mundane footfall in City Centre from first floor of the rundown Sikh-run eatery. “When plains drain me out, I came here to reclaim myself. I was once there, frequenting those streets below, and dreaming about the life which was soon-to-be lost.”

As he sips his tea with a recluse resignation—gazing the deceptive bustle down the streets, one is reminded of the artist’s longing in Munshi. Unlike many discontented souls who suffered the history, he doesn’t badmouth about his own people, whom he wants to greet with a hug.

But as a Kashmiri, he makes no bones about the perpetual state of political situation in his homeland. “There’s a problem,” he says, with a straight face, “and it needs a solution.”

He throws his weight behind the artist’s neutrality in the current polarised times, when many in his tribe are openly endorsing a particular shade of politics and take an unabashed stand on political matters.

“At times, yes,” the artist turns attentive, “people tend to seek your opinions about every newsy issue under the sun. But when it’s a question about my roots, I always maintain that Kashmir is like a big canvas for me, which has lost many of its details. As an artist, one can only apply compassionate touches to portray and present its reality. That’s what an artist should do.”

Perhaps, it’s this compassionate native sense, which often gets reflected from his works. He never shies away to project and portray some hard realities of his homeland. His artistic career is full of instances when he led from the front to highlight his home situation through canvas.

When the 2010 street upheaval thawed, Munshi started his well-known shrapnel art series to portray that summer storm. It was an artist’s ode to the simmering street situation, shaping up a new Kashmir discourse.

Again, when floods hit the valley in early fall of 2014, he came up with distressed portraits of commoners caught in the deluge. He calls that canvas of his as a cathartic experience. Later those portraits make up Memoir, a grid of 101 portraits.

A year later, Munshi stunned many connoisseurs—when he installed the pitch dark toppled boathouse in India Art Fair. For art patrons, it was a window to see and experience how Kashmiris braved floods. To recreate such experiences, he says, he keeps revisiting his roots — both in mind, and body.

Inside the hushed eatery, he doesn’t make much about those art projects. Through his weighing silence, he seems to communicate that one does not always need to take a credit for presenting the home reality.

In that same home now, he mainly roams as a tourist — wandering, and perhaps making for his lost love.

A few years after the migration, as a struggler, he had bumped into his misplaced beloved in Delhi. But he couldn’t make it up with her, again. In migration, perhaps, some other things had taken precedence for them. And now, like most artists, Munshi carries a lost world with him.

But before migration would flip his world, he was aspiring and training hard to be an artist. He describes that early phase of life as some kind of a mad devotion.

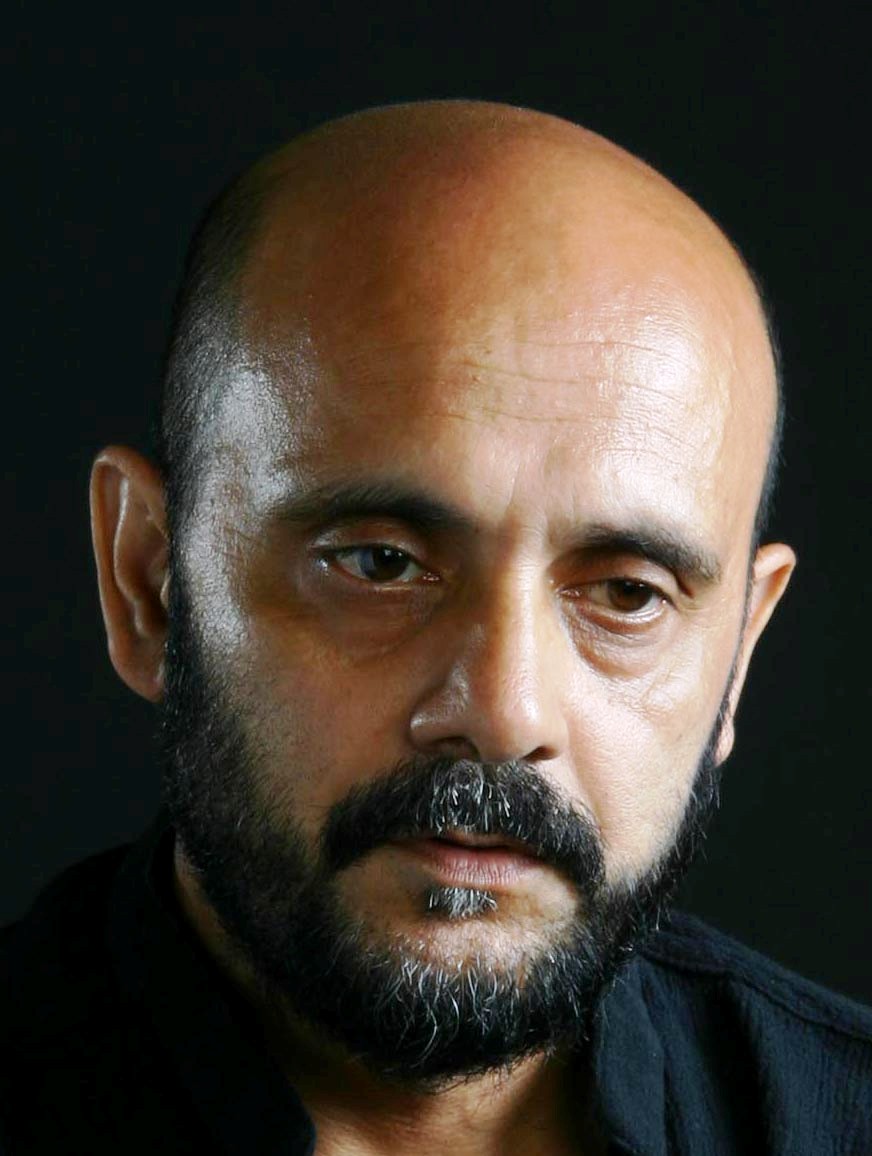

“Even before the political storm started gathering in Kashmir towards the fag-end of 80s, one could see it coming,” Munshi continues in his husky voice and thoughtful beardy-bald appearance. “But, yeah, after doing graduation in Humanities from SP College Srinagar, I was trying to give voice to my artist. With likeminded people, I even started a magazine. But then, life had other plans for you. In a jiffy, it all ended.” Later, Munshi would acquire a BFA in painting from Baroda.

In Delhi, where he suddenly found himself grappling with existential crisis, he had to brave the burning longing for his roots under the scorched sun. But even as the odds were highly stacked against him, he began canvassing Kashmir and its turbulent reality. Delhi’s art circles and patrons, however, took time to notice the young painter’s artwork detailed with desolated landscapes and angst-ridden people.

That was the time when many in his tribe were using hardened political statements. But Munshi relied on his canvasses to portray the horrors of his homeland. Through his art, he wanted everyone to understand the valley’s pain, fear and turmoil.

“Through my artwork, I wanted to make my viewers aware about my home and myriad hues,” he says, matter-of-factly.

But for doing that, he had to go empty-stomach for days together, before Delhi finally noticed and embraced him. Despite that early phase of success, he slogged and kept bettering his canvas.

Within a few years, his intensity as an artist made him a new sensation, with who’s who in the art world appreciating the new artist in town. Much of that appreciation came from his ability to telescope images of pathos and abhorrence over his ‘lost Kashmir’.

That early appreciation helped him to scale new heights in the art world. Years later, as he rose to become one of the finest—and celebrated—artist in India, he started showcasing his works in China, Mauritius, St Petersburg Russia, Havana biennale Cuba, Vietnam and many other nations.

But before becoming a globe-trotter of sorts, he had arrived in his birth place, first time after migration, leading a troupe of artists.

It was 1997, when he arrived to shoot a series of abandoned homes. That year, he led the team that designed Jammu and Kashmir’s Republic Day tableau and won first prize. From 1997-2014, he designed and executed 17 tableaus for J&K on January 26 parade New Delhi. Later, he would take home 2002 National Award from Lalit Kala Academy New Delhi and series of other awards.

For the first time, lately, he attempted to engage with poetry and stories, incorporating the works of Lal Ded, Allama Iqbal, Ghulam Ahmad Mahjoor, Agha Shahid Ali and others. He created skull of these writers with the help of paper-mache. Behind the concept, he says, was to give a visual tribute to these greats.

Away from his roots, he has created spectacular spaces in his two-and-a-half storey house in Gurgaon. In that recluse space, the intensity of his canvas has grown manifold.

What used to be a struggler some 30 years ago has now become a fêted artist who has moved to a deeper understanding of his homeland caught in a “memory and quandary”.

In May, he partnered with a Srinagar based artist, Mujtaba Rizvi, to get 40-odd migrants Kashmiri artists to an art exhibition in Srinagar. It was one of the major art events for which the organisers choose a century old Filature in the old silk factory at Solina.

There were two pieces of art by Munshi. First, he assembled abandoned pieces of equipment from the filature and arranged it encircling a crow, sitting on a rod. It indicated the ruin and the loss. The other was a Shikara turned upside down with wind chimes dangling down over a mirror. Perhaps it indicates an expression of an “out of box” thought process.

(This copy is an upgrade of the report was appeared in the print edition Vol 10, Issue 14.)