Khaal Baub has been quite a phenomenon of the Plebiscite Front in South Kashmir’s Bijbehara belt. Days after Sheikh returned to power, Khaliq turned a poet naturally. Aaqib Hyder met the man days before he breathed his last

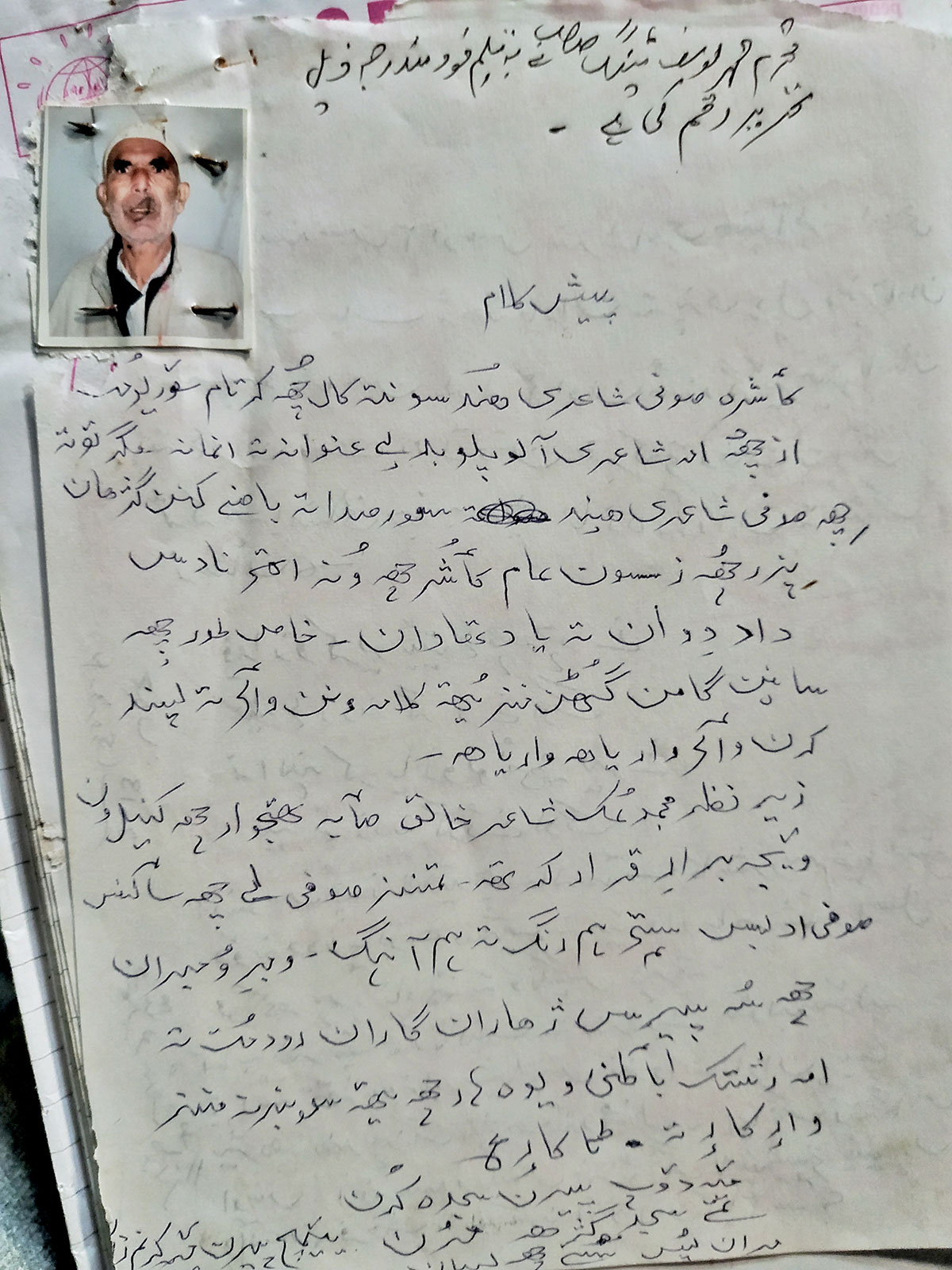

In Thajiwara, around 5 kilometres from Bijbehara, is a muddy cul-de-sac on the left side of the road that leads to a modest two-storey residence of Abdul Khaliq Dar. Born in 1932, Dar dies last week at the age of 86. But for many, he was, in a way, the face of the village. He was known as Khaal Baub, a short form of Khaliq the grandpa.”

A farmer for all his life, Dar remained bedridden for the last many years and the end came on April 10.

Dar in his youthful days was actively associated with the Plebiscite Front that was created after Delhi dethroned Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah and arrested him. The Front existed till 1975 when Sheikh returned to power after the Indira-Abdullah accord.

In the Front days, Dar along with few other residents would mobilise people and organize political meetings, rallies and protests. When asked what exactly they used to do, the response was curt: “Tehreek chalaawan” (We were managing the movement).

After a few minutes, as if realising he has missed something really important, he got up a bit from his bed and started talking with a tinge of bravado.

“One day we got to know that Congress party workers are passing through our area and we organized a protest against them,” Dar said. “When they arrived, we started shouting slogans in favour of plebiscite movement and booed them away.”

After taking a long pause and a short nervous laugh, he continued, “The next day, police came and arrested me. I was in jail for almost a week before I was let go.”

Although he didn’t open up about if the police harassment continued after his release the senior residents of the village say that he faced the fire from state authorities for many years.

“He once told me how he used to sleep in rice fields and granary (typical wooden rice storages called Kuetch) to evade arrest and harassment from police,” one resident, who knew Dar well, said. “It continued for quite a long time.”

In the early eighties, Dar went through a strange state of mind which he could not understand himself. Occasionally, he started feeling as if he was being weighed down by something and he was journeying into his own subconsciousness. This state was marked with an outpour of rhyming words which he would write in a diary.

“I remember it was the day of Eid and I was standing just outside my home when I felt a strong urge to write something,” Dar said. “I called my daughter and asked for a pen and paper and wrote my first ghazal. I wasn’t aware that this was going to be a long journey.”

Few couplets from the ghazal he wrote that day:

Yemich Meh Peeran Kaernam Zaan,

Tee Chum Deedhan Tal Chamkaan.

Meh Taem Hownaem Soaruie Galtaan

Tee Chum Deedhan Tal Chamkaan.

Meh Hoove Peeran Shariyath Paalun,

Tareeqat Zaenith Paan Gaalun

Haqeeqat Nish Chus Bah Larzaan

Tee Chum Deedhan Tal Chamkaan.

(Of what my Peer’s awareness (in me) necessitated,

that all in my eyes is illuminating.

He unfurled the entire treasury to me,

that all in my eyes is illuminating.

My Peer to me the code of conduct confirmed upon,

that Tariqat leads to annihilation.

The state of Haqeeqat sends a shiver down the spine,

that all in my eyes is illuminating.)

After delving into the mysterious matters and concepts of life, fate and internal chaos for quite a long time, Dar says the involuntary outpour sustained effortlessly. He doesn’t think of it as a choice which he made but a divine intuitive gift or, a much inclusive term ataayi, as he calls it. Chasing spiritual questions about destiny, faith and life itself, he has put more than 220 monologues and dialogues in the form of ghazals on paper. For example, the dialogue in this poem addressed to God is so strongly evocative.

Kas Kyah Lyookhuth Azlaekis Khattas,

Meah Haa Pyow Tchyeatas, Chuss Haeraan.

Jiger Chum Dodhmut, Tchyea Siwaa Waneh Kass,

Meah Haa Pyow Tchyeatas, Chuss Haeraan

(Whatsoever (You) in one’s fate wrote,

my recollection dawned upon me the wilderness.

My inner heart (You) ablazed,

to whom, save you I shall reveal)

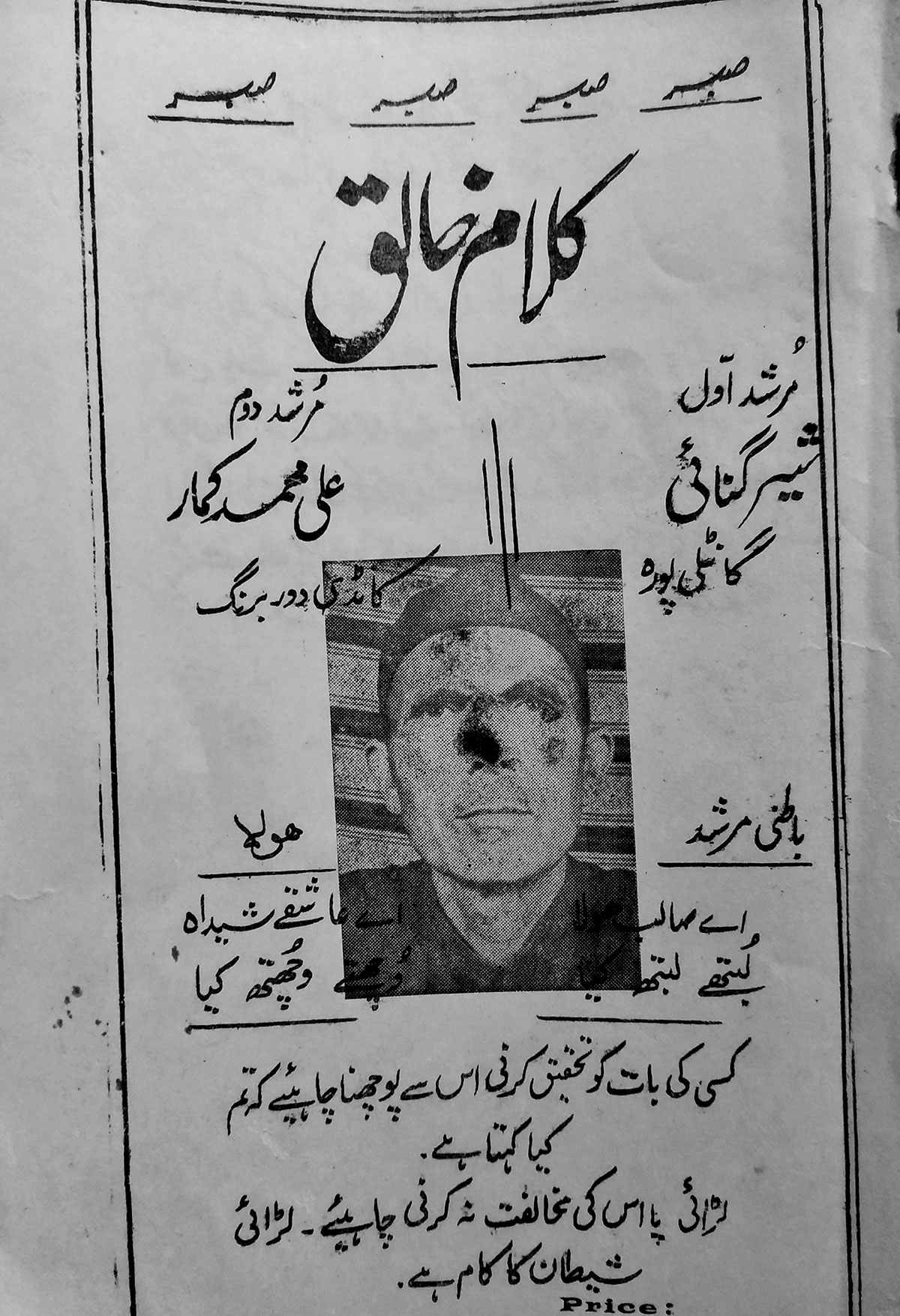

With an intention to solicit expert opinion on his work, he sent a diary with around 200 of his poems to renowned Kashmiri literary critic and author Muhammad Yusuf Taing in 2013. After some time, he received a letter filled with praises and positive criticism from Taing. It is possibly the only serious literary opinion about his work till date. Dar has preserved the letter as a holy relic.

“The poetry collection of Abdul Khaliq is totally in accordance with the quintessential Kashmiri literature in general and Sufi poetry in particular,” Taing’s two-page letter reads. “Every poem gives us a peep into his chaotic self and search for a spiritual mentor.”

Few of his poems were also broadcasted from Radio Kashmir Srinagar after they were recorded in his home. Moreover, his poems are religiously recited and used in musical performances in a wide range of sufiyana mehfils and songs in the region.

One wonders why a man with a strong politically active background would take a U-turn to land in Sufi poetry, which is considered as deeply apolitical. This big a shift in one’s ideology can’t be seen as a mere coincidence. After the 1975 accord by Sheikh Abdullah marked the dissolution of Plebiscite Front and its demands, even the diehard supporters like Dar became disillusioned. The move was seen as a clear sell-out by people and an insult to the struggle of sincere supporters. Dar says that after the surmounting human rights abuses and ultimately the eruption of militancy, the accord came off as a clear betrayal to us.

“We eulogized Sheikh Sahab like anything but as the infamous accord started unravelling itself, politics and our struggle felt like all in vain,” Dar said in March. “Then God bestowed upon me the gift of poetry and I took my leave from the fray.” His reverence for Sheikh, however, has not changed as he would suffix ‘sahib’ to Sheikh’s name every time.

Owing to multiple health issues, Dar has not been able to write a single verse for the last couple of years now. After his only published work became a victim of reckless errors by the publisher and he had to burn most of the copies, he fears that the poems might not see the light on the firmament of Kashmiri literature ever.

While fixing his stare on the large oxygen cylinder reclined against the opposite wall, he concluded: “Given the number of poems I have written, I can easily get two more books published but my deteriorating health cuts the plans short every time. At times, I couldn’t even get up on my own; writing a poem or publishing it is a distant thing now.”