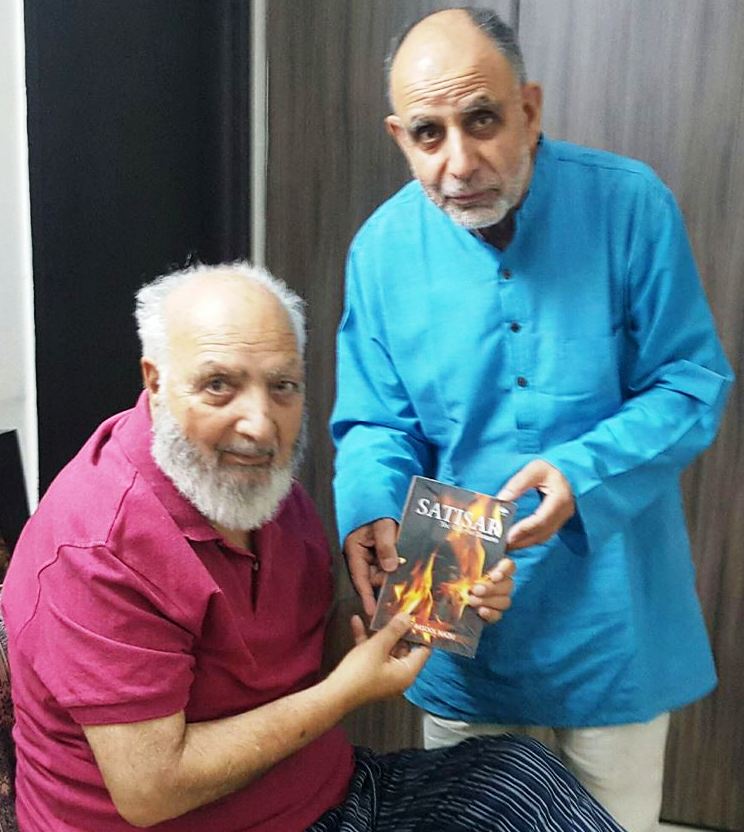

Ayaz Rasool Nazki’s novel is something that can be read with all the loud guffaws but it pains if one tries to understand the tapestry of chaos that weaves all the characters together, writes Shabir Ahmad Mir

Some thirty odd pages into Satisar: The valley of Demons by Ayaz Rasool Nazki and the reader is flabbergasted. For what else can a reader do when he, in a mind-boggling-quick succession, comes across such a wide assortment of characters arrayed in such bewildered situations – Kashyapa is on the verge of exile from Kashmir, Gani Kashmiri along with a Mulla Fani are paraded through a crack-down, Lal Ded is roaming naked through the saffron fields of Pampore, Yousuf Shah is rushing to GN bakers to arrange bakery for a Birbal, Maqbool Dar is scheming with Ajab Malik to incite an uprising…

And suddenly the reader must need to ask himself, “What exactly am I reading?” the answer is not simple. Satisar uses almost all of the techniques from the post-modernist fiction kitty-anachronism, pastiche, parody, inter-textuality, black humour, fragmentation, irony, fabulation, historiographic-metafiction, maximalism, and paranoia. Satisar abounds in all of them and more. And add to this the confounding resources that Nazki summons up from his formidable scholarship in mythology, folklore, history, metaphysics, philosophy, reading of Satisar becomes a challenging task. At this stage a reader is prone to commit to the fallacy of considering Satisar as an Alif Laila of sorts, that is to say, a conglomeration of quirky, fantastic tales.

One may even argue that Nazki, the author, is the Scherzade here and the tale-within-a-tale framework of One Thousand Nights and One has been replaced by the tale-besides-tale of the Satisar. But grant some patience and perseverance to the Satisar and you would soon realize how Nazki is weaving a tapestry with several threads crisscrossing in a seemingly disarray and lack of order and not just accreting fables and tales. And mind you it is a tapestry of chaos that he is weaving, after all, that is what the Kashmir at present has been reduced to- the bewilderment, the confusion.

Soon enough, the reader’s patience is rewarded (and helped along by the raucous wit and humor that abounds all around) as he picks up the major story-threads: the Kashyapa-Jalabdhava-Nilnag thread; the Budshah-Yusuf shah thread; the Lal Ded-Lally Dorabi thread; the Gani Kashmiri-Fani thread; the Maqbool Dar-Ajab Malik-Noshlab thread; the Birbal-Yousufshah-Mahaballi thread; the Raja-Ram Dev thread and by the end the reader sees how all these threads criss-cross each other and complete Kashmir’s jigsaw puzzle.

This interesting edifice- this scaffold over which the whole book is built- is one of the better elements of the Satisar; the other element is the ‘Characters’ (not characterization) Nazki adopts rather than invents characters. He adopts them from a wide variety of sources. Thus there are characters adopted from myth, folklore like Kashyapa, Jaladbhava, Birbal; from history like Budshah, Yusuf Shah (Chek), Kalhana Pandit, Rinchen; from literature like Ajab Malik, Noshlab; from urban legends like Charles (Shobraj). Then there are characters who are real-life persons of contemporary times as well as recent past who have been fictionalized under caricatured names like Laila Dorabi, Raw Kaw, Mahabali, Todermal, Maqbool Dar, Mulla Nateg Shirazi, Maharaja Keran Rajput etc.

What is interesting to note here is that the adoption and fictionalization of characters by Nazki is not plastic but rather organic. He not only uses the actual historicity of his adopted and fictionalized characters but he goes further and builds upon his characters by superimposing personalities of more than one historic and or contemporary figure into a single character and by means of parallels and contrasts creates a composite hybrid. Kashyapa, for instance, is not only the mythical Kashyapa Rishi but he is also Kashyapa the exiled Pandit as well as a loosely fictionalized substitute of Sheikh Abdullah and by extension every politician who chose mainstream politics.

Similarly, Yousuf Shah is Yousuf Shah Chek as well as Syed Mohammad Yousuf Shah (aka Syed Salahuddin) and at the same time, he is also the stereotypical Kashmiri up in arms against the establishment. Lally Tigress/Lally Dorabi is the archetype suffering mother and is Lal Ded of yore as well as the contemporary women chief of the renowned Dukhtaran. One may also mention here the appreciative resetting and retelling of Gulrez. The Ajab Malik-Noshlab love story, their German travail and the sprinkling of sci-fi towards its end: everything has been done with a fine taste. Ayaz Rasool Nazki by some deft touches and brilliant inspiration has created such a plethora of characters who find their parallels in the Kashmir of the present as well as Kashmir of past; in the Kashmir of myth as well as in the Kashmir of turmoil, thus investing in his narrative a broader framework and depth.

Despite such promising and brilliant scaffold and characters Satisar still falters. Firstly, it falters due to the excessive fragmentation of the narration. No sooner has a reader invested himself emotionally and mentally with a Kashyap and Kashyap’s story than he is uprooted and transferred to the world of Gani Kashmiri and his ordeal. Again just as the reader warms up to Gani Kashmiri he is again dragged away and thrust into the travails of Budshah. Coupled with the rapid pace of plot and narration the reader is dislocated and relocated so frequently the book struggles to maintain the attention and focus of the reader.

Another weak point is the plot overall fails to keep up with the promise of the premise and the characters on which Satisar starts off. The story lines are not weaved in to create a composite whole, they just stick out. One may argue that this sticking out or this chaos is intentional as it does what it is supposed to do – portray the actual ground reality of Kashmir i.e. the confusion and the chaos but there remain problems within the storylines as well which cannot be justified.

Most storylines end on a false note without giving the reader a proper denouement. The author resorts to the indiscriminate use of deux ex machinas. Then there are also scenes which are full of clichés and read like stereotypic Bollywood set pieces like Lally holding a gun to Colonel Sharma at the airport or the frequent use of sleeping vibhutis and pills.

Nevertheless, Nazki shines in individual storylines. The Kashyapa-Jaladbhava-Nilnag storyline is a brilliant exposition of the history and its subaltern reading. Kashyapa the liberator is Kashyapa the invader for the aborigine Jaladbhava: his usurpation of the throne and the subsequent corruption opens up history to a new debate and at the same time parallels the political trajectory of Kashmir’s greatest leader of last century. Jaladbhava can no longer be called a demon. And again by creating a contrast between Kashyapa the invader and Kashyapa the exiled, Nazki very subtly presents a critique of aborigine-foreigner debate of ‘Kenan Kashmir.’

The storyline of Yousuf shah-Budshah is a deft portrayal of the armed resistance-the naiveté of it and the politics thereof. Gani Kashmiri’s storyline is a superb delineation of the absurdity and the horror that every Kashmiri’s lot has been reduced to in the last couple of decades. The only false note in this story arc is the metaphysics that creeps into it towards its end. The metaphysical yearnings look forced and out of place here. Gani Kashmiri (as well as Budshah) inhabits a Kafkaesque world where suffering and horrors pile up on him. His sole offence is his existence in such an absurd world. No metaphysics, no morality, no ethics will ever provide him with any relief. He ought to have been left as such- a near perfect Kafkan anti-hero. Metaphysics should have been left to the story arc of Raja Ram Dev and Nand Gupt. It belongs there.

To sum it up Satisar: The Valley of Demons can be read with all the loud guffaws and broad smiles; and only when one starts to ponder about it, it will hurt.