By Younis Kaloo

“It is my turn, Rehet Mouj’i.”

“No, no, it is mine. Give me first, Rehet Mouj’i.”

“I have enough for all of you. Have faith in God.”

Rehet Mouj is not distributing Teher but looks through a crevice, formed by the two hanging drapes on the roadside window, at her house’s veranda. Her partly grey hair and face are tightly wrapped with a plain white stoal to mitigate the effect of the unpleasant teargas smoke, which eddies through a broken window and an-inch high chasm between the main door and the floor.

It is just half-an-hour past a mild incident of stone throwing between government forces and the protesting youth, whose number, as the summer heat turns into pleasant autumn sunshine, is reduced from many to few.

In the smoke that wafts from the dying teargas canister outside Rehti’s veranda, appear to her the images of children, men and women who would throng in the days—when Rehti would accompany her elder son’s children to their school in the morning and reach twenty minutes before they signed off—to receive her Teher in hands, platters, and bowls of copper and steel.

Piercing further her gaze through the thin cloud of the smoke, her eyes catch a glimpse of the world just across the river, Sukhnag flowing gently from the front of her house. Bush ash covers the dike, which divides the river into two branches flowing parallel to each other. A handful of yellow mulberry tree leaves, on the bank across the river, make it to the branches. The dull blue smoke emanating from the dunes of cow dung. And the government forces, some reclining with the tree trunks, and their vehicles.

Piercing further her gaze through the thin cloud of the smoke, her eyes catch a glimpse of the world just across the river, Sukhnag flowing gently from the front of her house.

A month ago, in the village on the other side of the river, youth engaged with the government forces in fierce stone pelting. The latter would retaliate with equal magnitude using teargas, pellets, flash-bang grenades, dummy bullets, and, at times, fired live rounds. The bushes blocked the view for the people residing on this side of the river. So, on a day when youth on the other side were still sloganeering, few boys embarked a boat, took some kerosene in a plastic soft drink bottle and set the bushes ablaze. Within an hour, the fire engulfed the bushes and razed the entire patch of them to ashes.

Some police men, a week before, had also tried to set the bushes ablaze as some youth would hide in them, pelt stones from there, and would go unspotted. But as soon as the local youth came to know who shouted and raised slogans, the cops had to return before they could set foot on the dike.

In times when both the villages were protesting, some youth, who came from various adjacent hamlets of Narbal, would wade their way through the chest-deep water and protest from the dike. When this happened it meant a tough time for everyone: youth, residents, and the government forces.

There is no one out on the road except for the teargas canister, which, by now, breathes out in little puffs of smoke, a hen few houses past Rehti’s racking the loose soil with its claws and picking at whatever turns out to be food for her and her chicks, and, maybe, a dozen Paramilitary troopers with a few Jammu and Kashmir Police cops. They have come a long way from Narbal’s bus stand chasing down the youth and halted just outside Rehti’s concrete two-storey house.

Rehti shifts her gaze from hen to exhausting canister to the security forces outside, who are discussing about a boy who threw back a shell that hit him in the leg and how other boys managed to pull him away from them and saved him from being caught. This worries Rehti as one of her son, the youngest 16-year-old is among the protestors. But this fear is soon overpowered by another fear.

Her shouting caused Rehti to raise alarm until other women came running to her rescue.

Strangely, Rehti’s house has become a natural battle line between the youth and the security forces. When tired of chasing, firing teargas shells, pellets and bullets, they would stop just outside Rehti’s house. For government forces, it is strategically important in two ways: It rests in the middle of the hamlet, which allows them to establish control over half-of the hamlet until the day wears away, and secondly, beyond this house there are less alleys which prevent them from being corned from various ends.

But yesterday, when there were only slogans, taunts and abuses being exchanged between the two sides, youth and the security forces, a remark of one of the paramilitary man outside Rehti’s house brought alive a chilling memory of hers. In the remark the soldier threatened the protesting youth that they would barge inside all the houses, ransack everything, and beat everyone inside them. For Rehti, the words ‘everything’ and ‘everyone’ meant that they included her ailing husband, two daughters, and herself. She thought that the local police knew that her son protests and throws stones, and that this gives them more excuses and leeway to barge inside her house than being the first house in the reach.

The next morning she offered the pre-dawn Namaz and prayed to her God to stop the history repeating itself.

The presence of her two unmarried daughters reminded her of an early 2000s incident, which spiraled her worries in the present. It happened when in a ‘crackdown’ all the male members of all the households of the hamlet were huddled in the locality’s eid gah, while as, one by one, two youth brought from somewhere along with army conducted searches to find the hiding militants. It was on a dreaded Ikhwan man’s tip off; who resided in the next hamlet, that army had launched search operation in Rehti’s village. When such a situation arose, it was, by default, understood that women too would assemble at someone’s with a big house and a lawn in the neighborhood. But, then, this was not the case with two women. Rehti and her neighbor. They called to each other and had decided to leave after they were done with cooking.

By then, every house was under the eyes of one or two army personnel. The woman in the neighborhood did not have a house like Rehti’s. Her kitchen comprised a wooden hut built close to the façade of the house. A window in the mud-brick house and a door made of planks were two means of entrance and the exit of the kitchen. The neighborhood woman, however, was bestowed with sheer beauty. She was considered a masterpiece in the beauty in the locality. With no men home, the soldier outside forced his way inside and grabbed the woman. Her shouting caused Rehti to raise alarm until other women came running to her rescue.

This scene played over and over again in Rehti’s mind throughout the following night the paramilitary trooper warned to barge inside. The next morning she offered the pre-dawn Namaz and prayed to her God to stop the history repeating itself.

Rehti stands there in her room, the first from outside, amid bitter smoke, her eyes now fixed at the feet of the soldiers, worried if they barge inside.

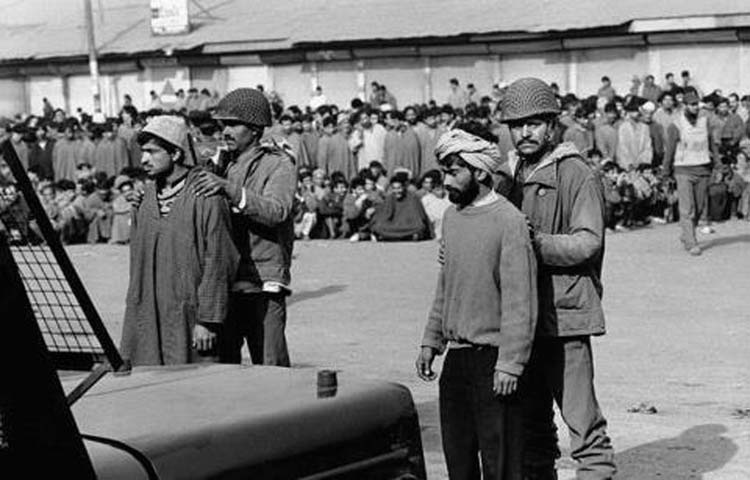

All the pictures used have no direct relevance with this story

(Younis Kaloo is a Journalism graduate from CUK. Ideas expressed are author’s own)