Right now when Kashmiri’s entire political class has launched a serious campaign to preserve the demographic composition of J&K, Dr Nitin Chandel details how Kashmiri Pandits and Jammu Dogras jointly launched a tireless campaign for the creation of the state subject classification in 1932. Interestingly, the majority Muslims didn’t matter then.

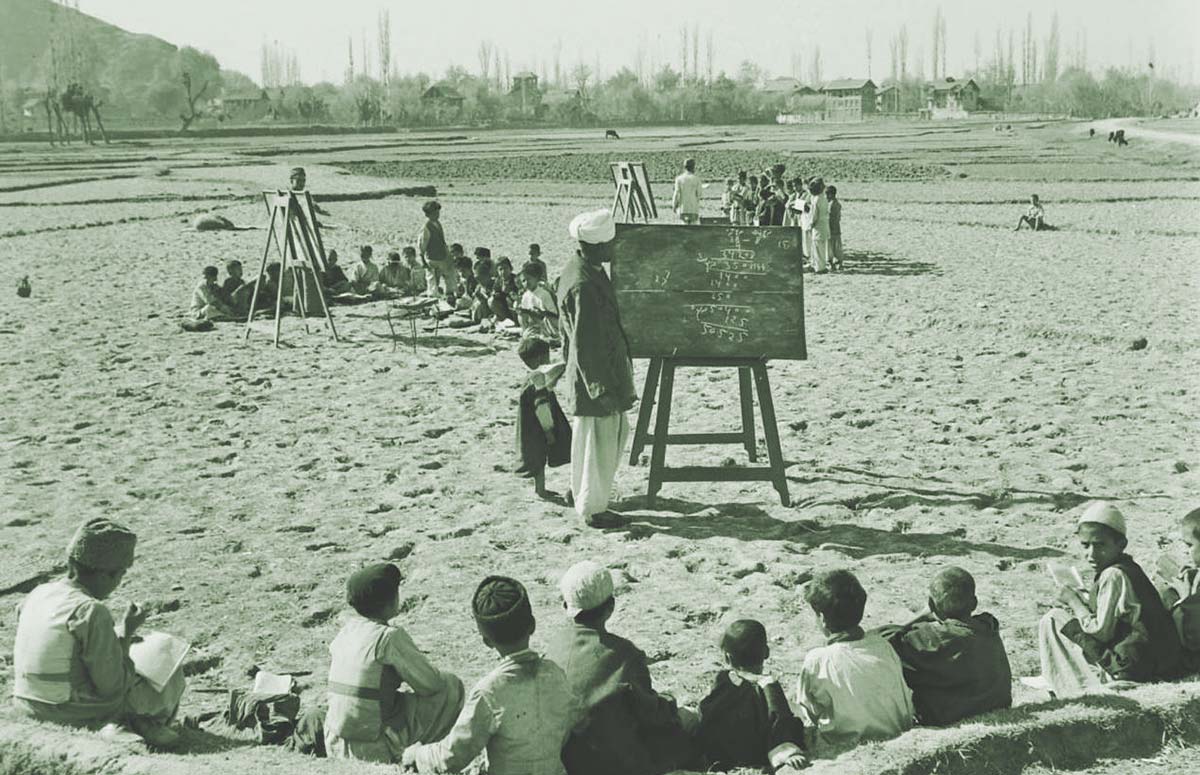

Early in 1905 A.D, a college was established at Srinagar with the efforts of Mrs Annie Besant and progressive Kashmiri Pandits namely Pandit Bala Koul and another college was also established at Jammu in 1908 which results in passing out of a large number of graduates every year. These young men who passed through these colleges have attained knowledge of western political thought; freedom and equality (see Bamzai, PNK, Cultural and Political History of Kashmir, Srinagar 1994, p119). The demand for a share in government services was first voiced by the Kashmiri Pandits who had come out fresh from colleges and acquiring proficiency in the English language; they challenged the administration of the State and the government to provide them with the necessary jobs in the state and not to Punjabis (Khan, G.H, Freedom Movement in Kashmir, New Delhi 1980, p26). The people of the State opposed the wholesale encroachment of all important Government posts, trade contracts etc. in the State by the outsiders. The outsiders commonly called Gair-Mulkies (non-natives) who were mostly Punjabis and their monopoly in jobs goes back to the reign of Gulab Singh when he appointed a Khatri named Dewan Jawala Sahai, who becomes the first Prime-minister under the Dogra rule who brings Punjabis along with him and employed them in the administration of the State. It is said that it was this gentleman who arranged the money which the Maharaja had undertaken to pay to the British in lieu of Kashmir. It was natural that he and his family/followers rose very high in the estimation of the Maharaja.

The result was the coming of many Punjabis, who received great reassurance at the hands of the Eminabadi Diwans (a trading business class). Extensive land grants were made in their favour and they were placed on many important chairs of trust and authority. Moreover, the commerce of the State passed into their hands. With the immigration of waves of the Punjabi settlers, the Pandits found themselves pushed into the background, though the process was slow.

The Kashmiri Muslims were not in the picture politically rather in the economic field they were a force as most of the economic activities were acknowledged by them. The outsiders were recruited in the state army with no interest than to draw as much as they could and then to depart leaving behind them their own kith and kin to continue the drain as mostly these jobs were latterly occupied by the outsiders too. Thus a hierarchy was established in the State services, with the result that, to quote the State Subject Definition Committee, services, profits and wealth passed into the hands of the outsiders and the native subjects lost enterprise and independence (Kilam, JL, The History of Kashmiri Pandits, Delhi 2003, p210). Besides, many Europeans had been transported into the State on high salaries. The survey officer, the chief Engineer, three assistant Engineers and the head of the forest department all these were Europeans (File No G-514 of 1911, Jammu Kashmir Archives-J).

Naturally, the natives were being deprived of their share in the services. They protested to the Government of India to give them an equitable place in the administration of the State. After consuming many representations from the native Kashmiri Pandits as early as 1889 AD, the Government of India took up the issue in the earnest. A telegram to the Lieutenant Governor of Northwest Province instructed him thus: “If Nisbet asks you for native officials for Kashmir. I hope you will kindly help him to get good men. It is very important to start with re-organization fairly and to avoid a Punjabi ring” (Kaur, Ravinderjit, Political Awakening in Kashmir, New Delhi 2001, p61).

This was the first kind of assurance from the Government of India to have emphasized on the burning issue of employment and the instruction to the governor of frontier province area comprised of Ladakh to recruit the natives was a sign of relief for the time being. Even the Maharaja Pratap Singh backed up the persistent representations of the people and directed that preference should be bestowed to State Subjects over outsiders in the matter of employment. Accordingly, in May 1904 AD, the State Council adopted the rules that all deserving State Subjects who sought employment in the State should be given preference over others who were either outsiders or had no special qualification for appointment in the services of the State (File No 40-S-18 Of 1904, JKA-J).

As a result of these developments, the Kashmiri Pandits had been appointed to various senior and lower grade clerical posts. By the year 1909 AD, a substantial number of Kashmiri Pandits had entered Government services but the high positions were still seized by the outsiders who were creating great difficulties for the natives to get higher promotions on the basis of their work and merit. This attitude of the outsiders had aroused strong feelings of resentment among the Pandits (File No 21/F-219 Of 1909, JKA-J). The outsiders who formed the majority in the Government offices and exercise an effective influence in matters of administration were taken aback. Since there was no well-defined definition of the term State Subject on record, these outsiders persuaded the Maharaja to define the term in such a manner that the services, trade and property of the non-State Subjects of the State would be protected (File No 63/F-101 Of 1910, JKA-J). In June 1912 AD, the term State Subject was defined for the first time with the ostensible purpose of giving practical shape to the command of his Highness the Maharaja to meet the persistent demand of the people of the State to safeguard their rights but it did not prove operative because any person could have declared himself a State Subject, simply by putting an application on a stamped paper of eight annas without qualifying any preliminary (ibid).

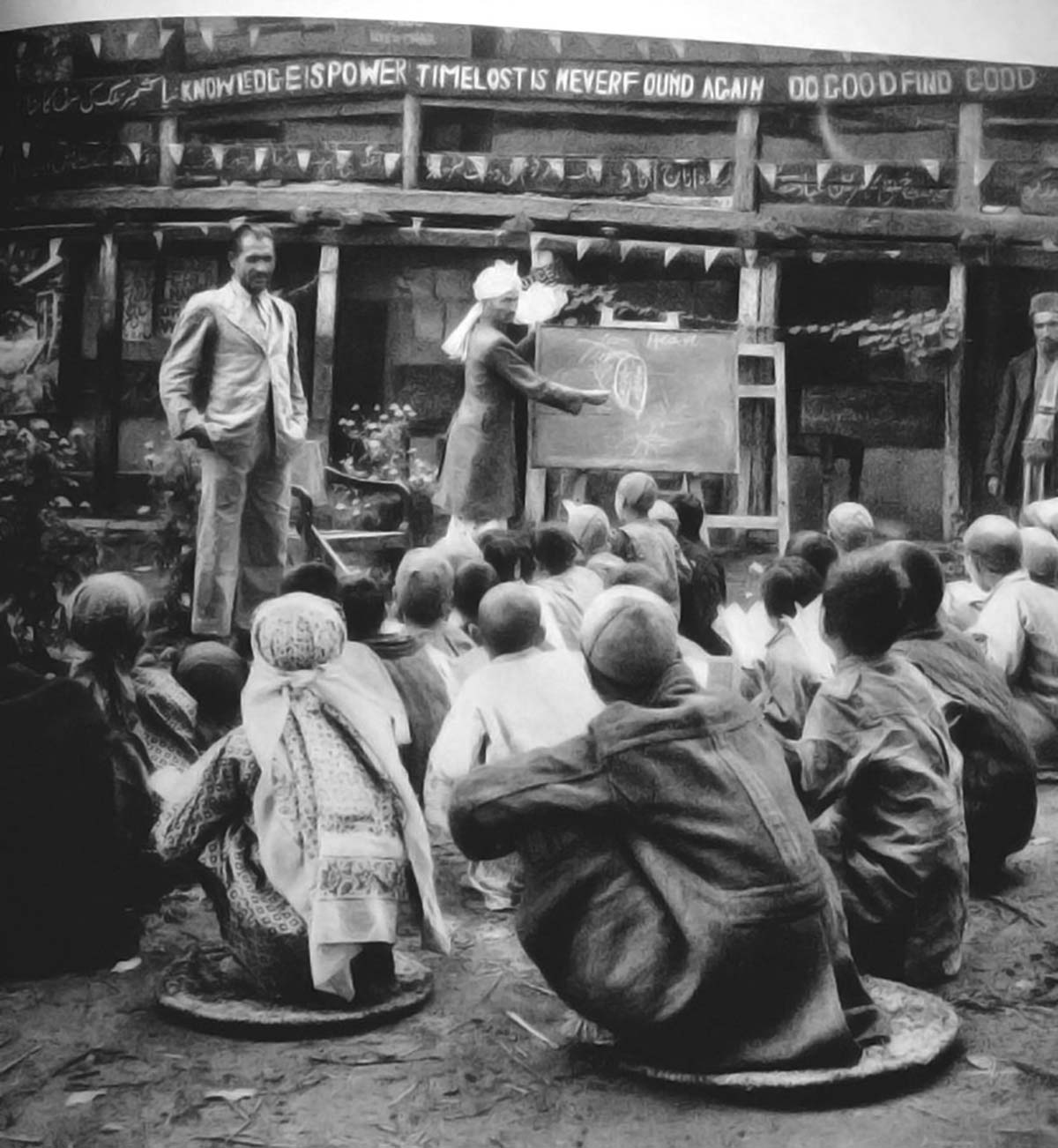

Moreover, the Definition was so loosely worded that it afforded little relief to the people and the resentment among the educated classes went on increasing day by day and they took the formula of agitation (Khan, GH, Freedom Movement in Kashmir, p102). The agitation was spearheaded mainly by the Kashmiri Pandits and the Hindus of the Jammu. They were the first to take to modern education, long before the Muslims of Kashmir became politically conscious. The Kashmiri Pandit fought for modernization of the administration. They were the first to demand a free press, a free platform and a legislature based on the qualified franchise, with powers of lawmaking, certain limited powers of financial control and certain supervisory powers over the executive (Kaur, Ravinderjit, Op cit, p30).

The unsatisfactory nature of the concessions of 1912 AD was highlighted by yet another Kashmiri Pandit writing under the pseudonym satis superque in 1921 AD in United India and the Indian States. He suggested that over the preceding decades: “Sites and plots have been acquired by outsiders who have humoured our being highness into condescension, by men who have either possessed influence with the Maharaja or have held some high and responsible positions in the State. A few months or years stay had given them hereditary rights of a State Subject to freely acquire lands whenever and wherever they liked. Ex-ministers who have some half a century back been in the State have come forward to assert their rights and secure some immovable property” (Rai, Mridhu, Hindu Rulers, Muslim Subjects, p252).

In 1922 AD, at the instance of Maharaja Hari Singh, who was then the senior member of the council, a committee was appointed to define the term Hereditary State Subject and examine the entire question of naturalization (Kaur, Ravinderjit, Op cit, p30). The heads of various departments of the State were directed to prepare a list of the Mulkies, naturalized mulkies and non-state subjects in the State employment. A circular was also issued over the signature of the Maharaja prohibiting the acquisition of land in the State by anyone but a State Subject.

The circular also said: “In future, no non-state subject should be appointed to any post without the express orders of the Maharaja Bahadur in Council in each case, each such proposals would be accompanied by a full statement of reasons as to why it was considered necessary to appoint a non-state subject, it considered necessary to appoint a non-state subject, it being definitely stated whether there was no state subject qualified available for the appointment proposed. In like manner, no scholarship or training expenses of any kind would be granted to non-state subjects” (A Plea for State Subject Definition and its Genesis by Dogra Sadar Sabha, Jammu).

But this definition made no impact and nothing came out of it. One objective of these attempts at fashioning a broader alliance also evident with the Kashmiri Pandits and the Dogra Sadar Sabha working together in the mid-1920 was to obligate the definition of the term Hereditary State Subject altered to exclude encroachment on State employment by outsiders (Political Department, File No 73/97-C of 1921, JKA-J).

At Jammu, the struggle sprouted forth into the Dogra versus the Punjabi controversy. In Kashmir, the British officers encouraged the Pandits and even sided with them in their struggle against the outsiders. The outsiders were generally Arya Samajis with whom was associated the name of Lala Lajpat Rai. They had a connection with their home province and whenever they returned from there after a brief sojourn, they came laden with fresh ideas. This was an anathema to the British and hence their partiality for the Kashmiri Pandits (Kilam, JL, The History of Kashmiri Pandits, p220). Pandit Jialal Kilam, Pandit Shankarlal Koul, Pandit Jialal Koul and Pandit Jialal Jalali – all of them fresh from the college started an agitation through the outside press for securing the rights of the State Subjects. Jialal Kilam organized the public meeting and held conference both at Srinagar and at Jammu under the auspices of the Dogra Sabha. A sort of vague nationalism was taking roots in the minds of the educated class and in face of the common outside menace; the educated classes both of Jammu and Kashmir felt a sort of common kinship.

A batch of Pandit delegates attended the Jammu conference, and the educated lower-middle-class youth who were mostly Hindus of both the provinces founded a common platform for articulating their grievances (Ibid).

In 1925 AD, an article appeared in the Akhbar-i-Aam, a newspaper in Lahore, written by Pandit Gwasha Lal Koul under the heading Unemployment in Kashmir. The author appealed to the educated Kashmiris to elevate the sort of agitation in Kashmir that the student community had raised in China. Besides, he addressed a representation to all the members of the State Council in which reference had been made to the French revolution (Kaur, Ravinderjit, Op cit, p31). In the article, Gwashalal Koul wrote: “The awakening in Hari Singh caused by western influence had done apparently no good to the people committed by destiny to his care”. He further stated: “The old Maharaja’s absolute power was curtailed by the creation of the State Council which consisted of five members, four of whom were especially non-state subjects of different nationalities. The huge salaries which they and their assistant were drawing almost drained the state treasury while the qualifications they possessed hardly deserve the average clerk lot”.

Gwashalal Koul alleged that the people appointed from outside fed on the people who were “tottering and hastening into the jaws of depth: they dare not open their lips because the rigid laws that govern them had eaten all sap in them”. He further wrote: “Whenever a post fell vacant either by death or retirement, it was filled by seniority from within or by jobbery from without; direct recruitment by competition, except in a few cases, is quite unknown on this side of the globe, the result is that the meritorious men starve and the favoured foot flourishes”. He explained how the State Subjects were expelled from their offices. If chance had posted a Mulkie (State Subjects) at certain place, a formidable conspiracy was made to work in his ruin till the fellow was obliged to resign; and when he vacated, his post was either brought under reduction or filled by some incompetent person from among the favoured, and such was the ugly situation in Kashmir. Authorities could not be blamed because people, especially the educated class were responsible. No representation without agitation is the rule of modern democracy. Unless some pressure is brought upon the authorities, there cannot be a redress of wrongs. Gwashalal Koul therefore, appealed to the educated public to organize themselves into an association and to solve the problem of bread peacefully, honourably and legitimately. Although very stern action was taken against Gwashalal Koul, he along with other educated young men carried a relentless agitation to the Indian Press for Kashmiris to be exclusively employed to man the administration (File No 334 Of 1925, JKA-J; also see, The Ranbir, Jammu, Vol 1, 10 March 1925, P 11).

The State Subject movement had a distinctive feature of its own as it amalgamated both the regions on this issue i.e. Jammu under Dogra Sadr Sabha and Kashmir under Pandits. One of the annual conference of Dogra Sadr Sabha held at Srinagar on October 1926 in which Pandit Jia Lal Kilam moved a resolution, demanding that only those persons whose ancestors had been residing in the state since the time of Maharaja Gulab Singh should only be considered as the hereditary State Subjects and be given preferential treatment in the state-services to such persons, who were residing in the state from the formation of J&K state i.e., 16 March 1846. The committee was urged to define the term State-Subject Definition as early as possible.

Finally, the issue came up again towards the beginning of the Maharaja Hari Singh’s regime. The Maharaja appointed a commission under the chairmanship of Major General Janak Singh, the then revenue minister, to define the term. The commission comprised officials and non-officials including the natives and the outsiders. The constitution of the State-Subject Definition Committee was broadly based and the representation was given to all the sections of the population of the state including the Kashmiris, the Dogra and the Punjabis.

Maharaja Hari Singh issued another notification, which directed all the Heads of the Departments to submit him the detailed information about the number of the State-Subjects employed in their respective departments. The commission submitted its report in 1927 AD, defining the term State Subject (The State-Subject Definition Committee under such situation remarked: “Services profits and wealth passed into the hands of outsiders and the indigenous subjects lost enterprise and independence. It was very difficult to do away with the outsiders’ hegemony along with monopolization of the state services. They conducted themselves in the state administration in such an organized and smooth manner that their absorption in the state-services was neither visible nor challengeable”. From A plea for State subjects Definition and its Genesis, A Pamphlet by the Dogra Sadar Sabha, Lion Press, Lahore, JKA, p2; also see, Khan, GH, Freedom Movement in Kashmir, p102).

This definition divided the subjects into the following three categories:

Class I: All persons born and residing within the State before the commencement of the reign of his highness, the late Maharaja Gulab Singh, and also the persons who settled therein before the commencement of the samvat year 1942 (1985 A.D) and have since then been permanently residing therein;

Class II: All persons, other than those belonging to class I, who settled there in the State before the close of the samvat year 1960 AD, and have since then permanently resided and acquired immovable property.

Class III: All persons, other than those belonging to Class I and Class II, permanently residing within the State who have acquired under a Rivatnama and immovable property under an Ijazatnama and may execute Riyatnama after ten years continuous residence therein (A Plea for State Subject Definition and its Genesis by Dogra Sadar Sabha, Jammu).

After the establishment of this definition in 1927 AD, every entrant into the State government service was required to produce a certificate of his being a hereditary State Subject of class I. These certificates were granted by Wazir Wazarat in whose jurisdiction the candidate happened to reside.

Parenthetically, it was the Kashmiri Pandits, whose untiring efforts, including agitation, led to the implementation of the State Subject Law. However, the agitation they conducted was on the purely secular basis- for all the people irrespective of the religion or caste to which they belonged (Bamzai, PNK, Cultural and Political History of Kashmir, p120).

This law came in response to agitation by Kashmiri Pandits against the importation of foreign civil servants from Punjab into the Dogra administration, resulting in a poor representation of Kashmiri Pandits in the civil service. Kashmiri Pandits, therefore, advocated for the issuance of a state subjects definition that would offer them advantages in obtaining employment.

Such matters were largely irrelevant to Kashmiri Muslims, who were shut out of the employment pool almost entirely, due to their comparative socio-economic disadvantage and the communal nature of Dogra rule (Ganai, Mohammad Yusuf, Kashmir Struggle for Independence (1931-1939), New Delhi 2003, p23).

This definition of state subjects was later adopted and subsumed, essentially unchanged, into the term permanent residents in the Jammu and Kashmir Constitution (Lamb, Alastair, Kashmir: A Disputed Legacy (1846-1990), Karachi 1991, p121). In the words of Bazaz, Kashmiri Pandits being far more advanced in the field of education, politically conscious and intelligent but “ultimately the definition proved a boon for the members of the majority community (Bazaz, PNK, Inside Kashmir, p549). Kashmiri Pandits was not confined to political rights but they were developing public consciousness in the whole province with the preferred circumstances.

(The passages were excerpted from Dr Nitin Chandel’s doctoral thesis titled Kashmiri Pandits In The Political History of Jammu and Kashmir (1846-1947). Completed in 2017 from the University of Jammu, the study is an original work done beautifully.