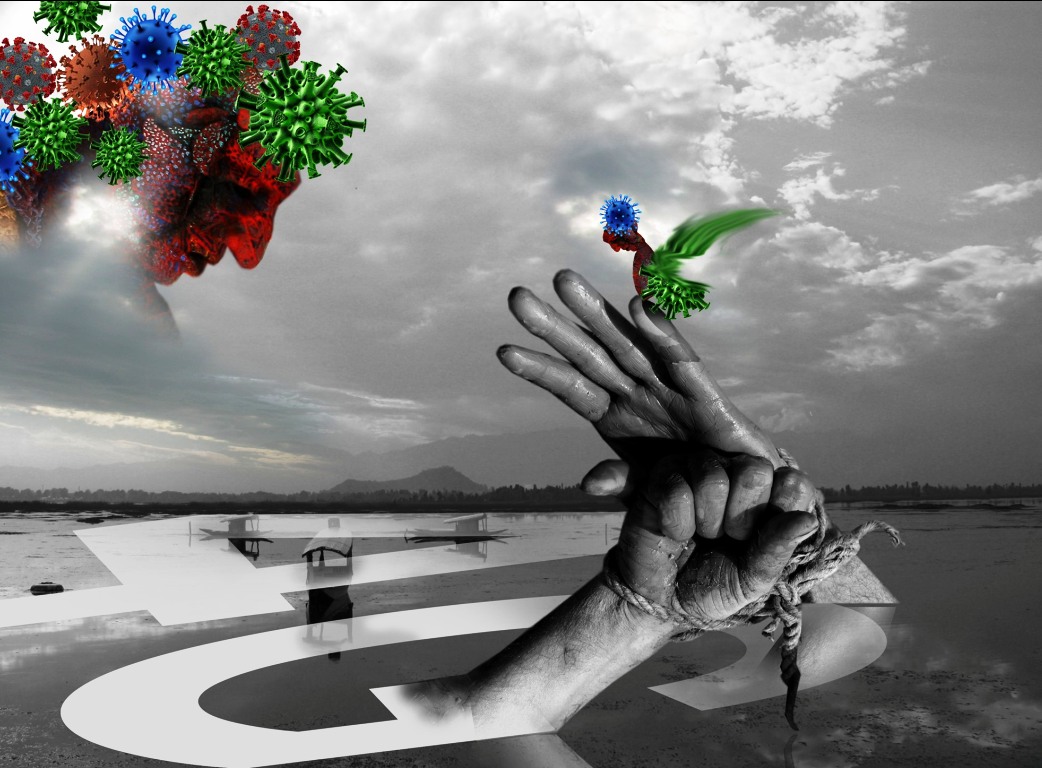

The continued ban on the 4G in Kashmir has created new records of the digital divide. But the questions being asked on streets are simple, why there is a sacred profane divide on basis of ISPs, reports Saifullah Bashir

The high-speed internet continues to be banned across Jammu and Kashmir since August 5, 2019. The ban is being reviewed by the officials on fortnightly basis and extended. The order being issued usually starts with this line: “…certain restrictions have been placed on access to high mobile data connectivity to curb uploading/downloading/circulation of provocative videos and defeat the nefarious designs of the forces within and from across the border to create a narrative by running a disinformation campaign.”

The latest read: “The apprehensions of the law enforcement agencies regarding misuse of high-speed mobile data services for infiltration and for coordinating (militant) activities get credence from the investigation of ongoing cases and the recent incident of interception of militant and recoveries of arms and ammunition, with increased activity on the IB/LOC.”

This frequent internet outage has given Jammu and Kashmir a dubious distinction of being the only place on earth that has so much of restriction on a basic service for such a long time. The Times of India recently reported, “India lost $2.8 billion due to internet shutdowns in 2020”. India has also topped the list of 21 countries with the internet shutdown of 8,927 hours in 2020.

But for all these months, post 5/8, not many people know a section of society across Jammu and Kashmir had the ultra-high-speed fibre internet. It was at the peak of communication blockade when the administration even paralyzed the fixed-line telephones that these superfast networks were operational.

“There were two sections of the society that had the internet facility when even media was not having one,” Abdul Rashid, a teacher in a private school said. “A private ISP was providing the service to the police and the Jio Fiber was having uninterrupted service in parts of Srinagar.”

This digital divide had triggered the very ominous question: “If 4G is hurting the security interests, how Jio Fiber is protecting the same?” This question was asked by people at multiple levels quite frequently but did not get a response at all. Tired of not getting a response, most of them joined the Jio bandwagon.

Sources told Kashmir Life that Jio fibre internet is currently being used by more than 27000 families in Kashmir. The numbers are increasing on daily basis.

The snow hit the network because more than one-third of their active connections were seriously impaired by the snow as the snow accumulations from the rooftops played havoc with the OFC lines.

The snow hit the network because more than one-third of their active connections were seriously impaired by the snow as the snow accumulations from the rooftops played havoc with the OFC lines.

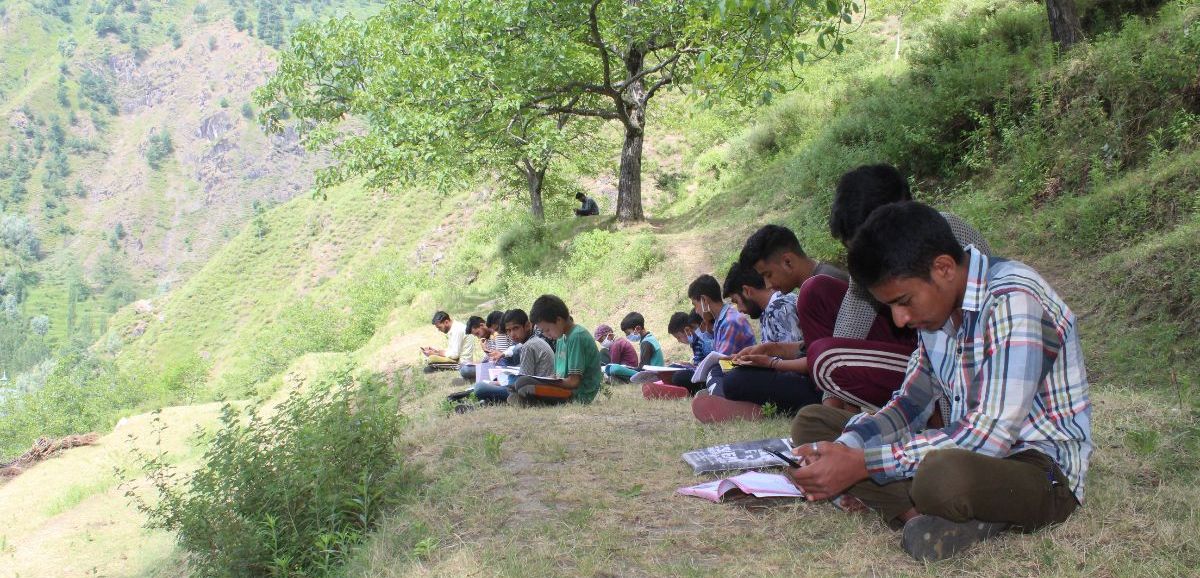

But the wait goes on. Mohammad Ayan, a fourth-semester undergrad student has also applied for a Jio connection. The snow has delayed the router installation at his home.

Though he has a smartphone but due to 2G bandwidth, Ayan said his studies are suffering, forcing him to get a fibre connection. For Ayan, the process of installation of fibre cost him Rs 3500 and then Rs 700 additionally as monthly recharge.

“This is not my requirement but helplessness,” Ayan said. “Some parents could arrange this money and some could not. But we have no other option left.” Had there been no ban, Ayan said it would cost him the same Rs 219 recharge, which he otherwise pays for nothing.

Raziya Noor, a journalist, has already installed one at home. She cannot manage her work on 2G and is not able to attend office because of Covid-19. “I hardly use 30 per cent of my plan data,” Noor said. “Fiber is not needed by me but I don’t have any other option.”

People are facing a lot of problems due to the ban. “Due to poor connectivity and 2G internet speed, people in general and students in particular, suffer,” Dr Imtiyaz Rasool Ganai, a resident of Baramulla said. “It is the need of the hour to install Jio fibre in our village for uninterrupted connectivity with high-speed internet. We request the concerned agency to install Jio fibre cables in Dangiwacha,”

Even people in the government are frustrated over the ban. At least, twice the Lieutenant Governor Manoj Sinha indicated that the services are being restored. His most recent statement was early this month when he said: “There is a committee examining the issue. Hopefully, there will be good news soon in the coming days.”

The Jio has triggered a competition. All other players are working overtime to have their pie from the lucrative Kashmir market. The government-owned BSNL is providing service to maximum government offices. “We have 15000 registered fibre connections and we continue to extend the service to rural areas,” Assistant Manager BSNL Muzzafar Beigh said. “There is a spike in demand from all sectors especially because the students have online classes to attend.”

Sources in Airtel said the company has not officially launched the fibre services in Kashmir but they are providing them.

The question is still unanswered: “If 4G is a crisis why not the Jio and others that following the big boss?”