The Rumours of Spring: A Girlhood in Kashmir that Harper Collins published last month is a stirring account of a girl’s life in 1990s’ Kashmir. Author Farah Bashir is getting rave reviews for capturing a situation that was frighteningly fluid, extremely explosive and painful at personal level. Here are two different chapters from the book.

‘Do you remember which cupboard the kafan is in?’

‘Yes. I’ll accompany you upstairs. There are other things I need to take out of the cabinet too, or else we’ll be scrambling during the morning rituals.’

Father left the room and Mother followed him. My aunt, Pophtaeth, and Ramzan Kaak were reciting the Quran next to Bobeh. No one sobbed loudly. The air was sombre as it is after the death of old people or those who die of natural causes, I thought, as I followed Mother and Father upstairs to their room.

Father unlatched the green door of a wooden cupboard in the antechamber adjacent to their room. Promptly, my eyes wandered to the large music system that they had bought from Saudi Arabia, where they, along with some other relatives, had gone for Hajj in the summer of 1988.

Other than the expected tabaruk – dates, Zam-Zam water, skullcap and tasbih – for relatives, acquaintances and neighbours, they’d bought many other gifts for friends and family members. Among the paraphernalia, crispy chocolate wafers were my favourite. The studded slippers were too gaudy for my liking and, luckily, a size too small, so I never got to wear them.

For himself, Father had bought a large ‘imported’ music system. Father didn’t particularly have varied taste in music. He was fond of Urdu ghazals by Mehdi Hassan, Kashmiri Sufi kalaam sung by Ghulam Hassan Sofi, like ‘Afsoosduniya kaensena loab samsar saete’, and some soulful ones, such as ‘Ruemgayam sheeshas begur gov vabaaneh myoan’ by Raj Begum and Naseem Akhtar. In those days, my favourite was a not-so-popular duet by Ghulam Hassan Sofi and Raj Begum: ‘Valle tai vasiye dokhsokh masherith’.

Before the big music system arrived at our house, we used to have a small stereo with two basic functions. It had a cavity to insert a tape into and an in-built radio. The new one had two spaces for tapes, an integrated, compact disc player at the top, and also a radio. Its edges were rounded and smooth, not boxy like the old one. It also had detachable speakers. All in all, it took up a fair bit of space. It stood out as one of the very few modern items in our traditional household.

Father rarely let anyone touch the music system. He was always around when he played it and after he was done, he stored it back carefully on the top shelf of the cupboard. He worried that if anything went wrong, the spare parts would be exorbitantly priced to be replaced.

Before my sister Hina got married, she’d take the music system out furtively and smuggle it into her room, which was next to the antechamber. She’d get home from college late in the afternoon, but several hours ahead of Father’s return from the shop. Hina would listen to her own tapes. Her playlist included songs by Pakistani pop artist Sajad Ali, ‘Hawa Hawa’ by Hassan Jahangir, and songs from Indian films like Tridev, Qayamat Se Qayamat Tak and Mr X in Bombay. Hina was very careful with the music system. She never forgot a tape inside and knew the exact angle at which Father had stored it in the cabinet.

Although, initially, she was apprehensive about letting me stick around during her clandestine musical afternoons, she came around after some months and let me into her surreal world. The only condition was that I made myself useful and did not disturb her. So, I’d pretend to prolong my homework and sit in her room with my books open. I was especially pleased when she played Young Tarang and ‘Boom Boom’ by the Pakistani sibling-duo Nazia and Zoheb Hassan. I liked Nazia’s singing and her signature nasal twang so much that I harboured a secret wish to want to be a pop-singer when I grew up and not a doctor like Bobeh wanted me to become.

After Hina got married, Father moved the music system to the lower shelf of the cupboard. Not that he suspected Hina, but he was afraid of an imminent destruction of the system at the hands of angry troops at the time of a crackdown. A fear that was more than understandable, because a crackdown was nothing short of an out-of-body experience, no matter how many times one had been through it. Someone takes over your house without warning or permission, ransacks your bedroom, goes through all your things, turns your house upside-down and you’re left either appeasing or pleading with them.

The sound of boots on the wooden staircase would spark off a series of tremors in me. I would break into a sweat and panic so violently that I’d feel as if I could vomit my heart out. The reaction of troops upon seeing the music system was usually, ‘Isskeliye paisa kahaan se aatahai, saale madarchod aatankvaadiyo?’ That had instilled in Father a deep fear: he was convinced that it was just a matter of time before they’d vent their frustration on his prized possession. It was a surprise that they hadn’t already.

Each time there was a crackdown, I muttered prayers hoping that no frustrated trooper tossed or flung the music system on to the floor even as they threw out utensils, clothes and books from the shelves, mercilessly, when ‘searching’ our kitchen and bedrooms.

A broken music system would be a loss to me than to anyone else. Father had more or less stopped listening to music since 1990. He was always on the alert for anything amiss and perhaps thought that the relaxation from music would come in between him and what was happening on the streets. For his news updates, he had a small transistor radio that he relied on.

When Hina got married, I stole one of her tapes, Young Tarang by Nazia and Zoheb Hassan. It included a mash-up of six of their best songs at the end of the album. Since school was hardly ever open in the three years between 1991 and 1993, quite frequently I’d carry the stereo to a forgotten storeroom at the back of our house, where Mother kept large trunks full of her trousseau and seasonal clothing. The dense air of the room was suffused with the migraine-inducing smell of naphthalene balls, but that never deterred me.

During those secret afternoons, nothing could stop me from dancing to Nazia Hassan’s ‘Boom Boom’ and ‘Disco Deewane’. I’d pretend to hold a mic, swing my waist and hips, twirling while the air gathered under the crooks of my arms. I did that repeatedly until I felt sweaty, tired and out of breath inside that dingy room. Panting, I’d step outside to inspect if the corridor was empty so that I could safely place the music system back into its original place. Much later, even after my heart had calmed down, the rhythm of ‘Boom, boom, dil bole boom, boom’ refused to disappear.

The Siege

Aunt Nelofar started removing the accessories off Bobeh to ready her for the final bath. She carefully loosened her mother’s tokke’ kor from her wrist, removed the coral ring from the ring finger of her right hand, as if not to hurt her, as if Bobeh were still alive. It was the ring that Bobeh had promised to give me as a present if I scored a distinction in my school-leaving exams, the previous year, in 1993.

‘If you graduate with a distinction, I’ll get you gold earrings that are bigger than I gave your sister,’ Mother had promised me. Father had promised to buy me a camera. Other relatives were expected to give token money as and when they would visit our home to congratulate me after the exam results were declared. There would perhaps be a small party. To celebrate her grades, a distant cousin had her ears pierced in the presence of guests. Another one got engaged during her celebratory party as her would-be mother-in-law was smitten by her beauty on the day of the function.

Graduating with a distinction was life-changing in many ways. While I was not inclined to get engaged or to have my ears pierced (I had mine done many years ago), I was looking forward to taking the big decisions of life. I was getting impatient to plan my life beyond high school. I was excited to finally give up studying subjects that I lacked interest in. I wanted to read Urdu for pleasure and not necessarily to pass exams or secure good grades.

‘Matric pass’ connoted a new life, a passage to freedom. Thereafter, one could choose to be anything: doctor, engineer, lawyer, lecturer! The azadi to choose one’s destiny! It was also for the first time that we could compete with the students across the valley and Ladakh, though not the entire state. The school term in Jammu had a different academic calendar from ours. Even though the board or the state exams were not supposed to be as tough compared to the ones held at school, it was the sheer number of pupils appearing for them that made them more exciting and challenging.

Owing to it being another unquiet year, just like the previous two, in 1992, schools across Kashmir had been opened sporadically and all of us struggled to finish our syllabus by ourselves at home. I was not particularly good at physics and had to seek help from my cousin who lived nearby. He would come over to our place to help me out whenever he could, but even that wasn’t enough. Indefinite curfew interspersed with civil curfew lasted for days on end. But private tuition or not, I was determined to secure a good percentage. I studied relentlessly.

‘Your future depends on these results,’ Mother would often say throughout the year. She said it more emphatically on the morning when Ramzan Kaak excitedly announced, as he walked into the living room with a phoat full of bread, ‘Date sheet tchu draamut.’

Looking at my exam date sheet printed in a newspaper, made it a big deal. In fact, I was so excited that I ran a mild fever for a couple of days. But there was worse to come.

It was the first week of December and our exams were to begin soon. Babri Masjid in Ayodhya was demolished. We, in Kashmir, were put under preventive curfew. As if we didn’t get enough curfews of our own. It impacted our exams. Postponements and rescheduling! The exams that were supposed to end in ten days took a month and a half to finish. I lost interest in getting a good score. It was difficult to maintain enthusiasm, and the curfews put our willpower to test. I didn’t care how well I did. I didn’t secure a distinction.

By the time the results came out – five months after they were supposed to – my excitement had dried up completely. The gifts promised to me by my family members were forgotten. There was no celebratory lunch at our house, not because of my grades (they were not shameful!) but the fact that between December 1992 and April 1993, another tragedy befell us.

After a gun-battle in Lal Chowk, near Palladium cinema, troops had set ablaze an entire patch of shops. My maternal aunt’s husband and some more relatives owned a few of them.

It was in the wake of that misfortune that Bobeh encouraged me to do better the next year. ‘Ye vaejj dime tczey,’ she promised to give me the heirloom ring again. The promise didn’t stir anything in me.

It seemed like the time of the exams had become jinxed. In October 1993, a month before the dates were announced for the final exams, militants had taken refuge in the Hazratbal shrine.

‘It is going to be Karbala this time. May Parvardigaar keep all of us in His safe custody,’ Mother sighed. ‘When Moi-e-Muqadas was stolen in the 1960s, thousands of people took to the streets. People would gladly lay their lives to protect the relic of their beloved Prophet (peace be upon him).

Thankfully, it had miraculously reappeared after two weeks on its own.’

With the siege and subsequent desecration of the mosque, despair and panic found their way into every house in our neighbourhood. Bobeh sobbed ceaselessly on her prayer rug. Father and Ramzan Kaak remained glued to the transistor radio for news updates.

The siege lasted for around forty days.

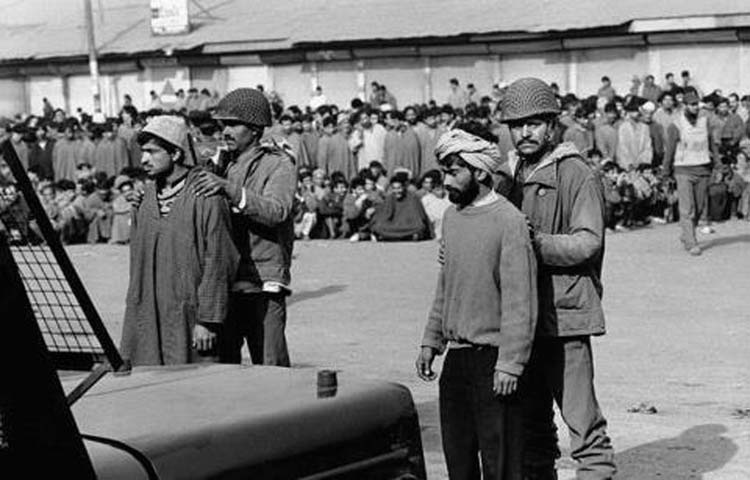

It involved prolonged negotiations between the militants and the government. Every other day, there were new demands from the militants and the state laid out new conditions. People, as expected, took to the streets, but the dense militarization ensured they did not reach Dargah. Scores of unarmed protestors were killed and injured that October near Vejbyoar.

Unsure of the outcome and the uncertainty that prevailed around the siege, I had lost the resolve to do well in my exams. What was the point? People were struggling to stay alive. How did my distinction matter? The round-the-clock curfew, the killings, the protests, the futile dialogues, the labelling of men sometimes as militants, sometimes as mercenaries … the constant shifting of power had done its damage. I didn’t know then, but it was the beginning of an apathy for my own self that would last for a long time. Our lives were controlled from elsewhere and the dreams that we dreamt were always at the mercy of someone else, someone occupying us, ruling us. The red of the coral of Bobeh’s ring just did not appeal to me anymore.

(These passages were reprinted with permission from Harper Collins India)