by Faizaan Bashir

Even though the government introduced an act to protect the handicrafts from perishing in 2006, banned machine-made goods, and came up with another policy in 2008, banning and auctioning the existing machine-made goods to the people, such policies aren’t strictly adhered to, and machine-made goods swamp the markets, pointing to the perishing of handicrafts in Kashmir.

Copper was discovered by early humans when they stumbled upon copper nuggets lying in streambeds. Fascinated by its reddish-orange colour, they recognised its malleability and usefulness. As time elapsed, people learnt the art of making objects from copper.

Historical data suggests that copperwork started in Egypt somewhere around 5000 BC. When people lit fire on mountains, it produced small red bubbles of fire on rocks, which were extracted and hammered thereof. The first object made of copper was a hammer, followed by weapons and jewellery. The people of Egypt used to bury copper objects with the deceased, as a token of love or as a matter of belief in supernatural entities or life in the hereafter. Copper was one of the materials that the ancient Egyptians used in making Pyramids, which still exist.

In Kashmir

During the reign of Shah Mir Sultan, copper ores, cloaked between the hard rocks and sand in mountainous regions, were discovered in Lolab Valley and Ashmuqaam, Kashmir. These copper ores, locally known as Kaani’ (mines) were smelted in large furnaces, followed by the process of creating copperware from them.

The renowned ruler of the Shah Mir dynasty, Zain-ul-Abideen, invited several Persian and Central Asian artisans, including copper workers, to Kashmir. He appointed them in different areas of the old city, Srinagar – which include Zain-Kadal, Mehraj Gunj, Kaid Kadal, Saraf-Kadal. Gaedbazaar, an area around Mehraj-Gunj, is still renowned for the crafting of big copper objects – such as water containers used in mosques. The craftsmen adorned the copper objects with intricate carvings. Most of the copper objects made here were then consigned to the rural areas for selling purposes.

They (foreign artisans) acted as a catalyst of change for the existing Kashmiri artisans, who were taught the advanced aspects of copperwork by them. It continued till Dogra times. However, after 1947, the copper workers of Kashmir started making varied copper objects: Flower vases, Shama Dana (candle holders), tea cups, dinner sets and many other things.

Shah Hamdan, a Sufi saint and scholar, had also invited and brought many Persian artisans to Kashmir. However, Zain-ul-Abideen would give so much emphasis on this craft that he immensely relied on the income that the copperwork generated.

In 1823, when English traveller Moorecraft came to Kashmir, he desired to know the location of copper-ores (perhaps to hold sway over them). To his dismay, Kashmiri exhibited utter cleverness by not disclosing its location, fearing the Sikhs, who were ruling over Kashmir then, would snatch this blessing of God from them. Copper was extensively used during the Mughal Period in Kashmir as well.

Copperwork in Kashmir is of different types which include Padri (copper objects made completely by engraving on them), Kandkari (intricate designs crafted on copper objects),Shafaqdaar (cut-work), Kamii Khanith (objects made complete by engraving on them shallowly.)

Zain-ul-Abideen would make metal money from copper. The making of which was done at Toonk-Sarai, Mehraj Gung.. Srinagar has remained the hub of copperwork for a long time. It’s pertinent to mention that downtown copperware is desired even in Iran and elsewhere.

Copper utensils in use for centuries include Tash-Naar (a pair of copper items used for washing hands), Samovar (a metal urn), Chai-Naar (a tea-pot) Daeg (a big pot-like object made from copper), jugs, Traem/Sarpopsh (Traem is a round plate-like copper item used to eat rice in; Sarposh – a conical copper artefact that covers it), Ezbandh-Sooz (an incense burner) and so forth.

Interestingly, roofing at certain places of the Jamia Masjid was also done using copper in 1955. People would also attach a layer of copper on the roofs of their houses in Kashmir.

Practitioners Speak

It first comes in the form of rectangular-and-round sheets of copper. \Rectangular sheets are used to make items such as Samovar (a metal urn made of copper), Steamers, and Water-containers. And circled sheets are used to make utensils like Toor (a copper item bulged inwards with a base, which is used to keep delicacies in), Kenz (a copper item which is used by Kashmiri women to eat rice in) and several other small items.

Firstly, these sheets of copper are marked with a sharp object, and then they are cut into small chunks of copper: spoons need a certain cutting of copper sheets; Samovar needs a different cutting of copper sheets, and so is the case with the other copper items.

Let’s take a look at how Toor is made: the artisan makes a rough draft of it on a sheet of copper with a stylus, then it’s accordingly cut with a sharp instrument (quite similar to scissors), which is used manually. These small chunks of copper are then formed into a Toor by affixing it with the material having adhesive features, followed by heating it in a furnace to the point the adhesive material dissolves into the copper and creates a durable bond.

After acquiring its desired shape, it’s hammered. Hammering gives the object a strong edge. And when the object is crafted, it is tied to a machine which moves circularly at bullet speed. The machine is used to clear the thick layers of dirt off the finished objects of copper. The machine is firmly installed in a certain place in a factory. A handle, on the other hand, sharp at the tip, is pointed at the copper object (which keeps on moving circularly as a result of tying it to the machine) to clear the dirt, without any damage done to the object in discussion. This machine is locally known as Charakh, the cleaner, who operates the machine, Charakhdar.

After the copper object is done, it’s cleaned further with water. The artisan then dries it, resulting in it acquiring a smooth and shiny finish. All circular copper articles – hollow in their structure – are to be Charakhed. As a copper item rotates with the machine, its inner surface remains exposed for cleaning. The other copper objects of varying shapes and sizes are cleaned by washing them with a brush, using a solution of water and sulphuric acid.

Thereafter design-makers, who adorn the copperware with intricate carvings, come into the picture. There are different designs that the craftsmen are skilled at creating, and some of them are as follows:

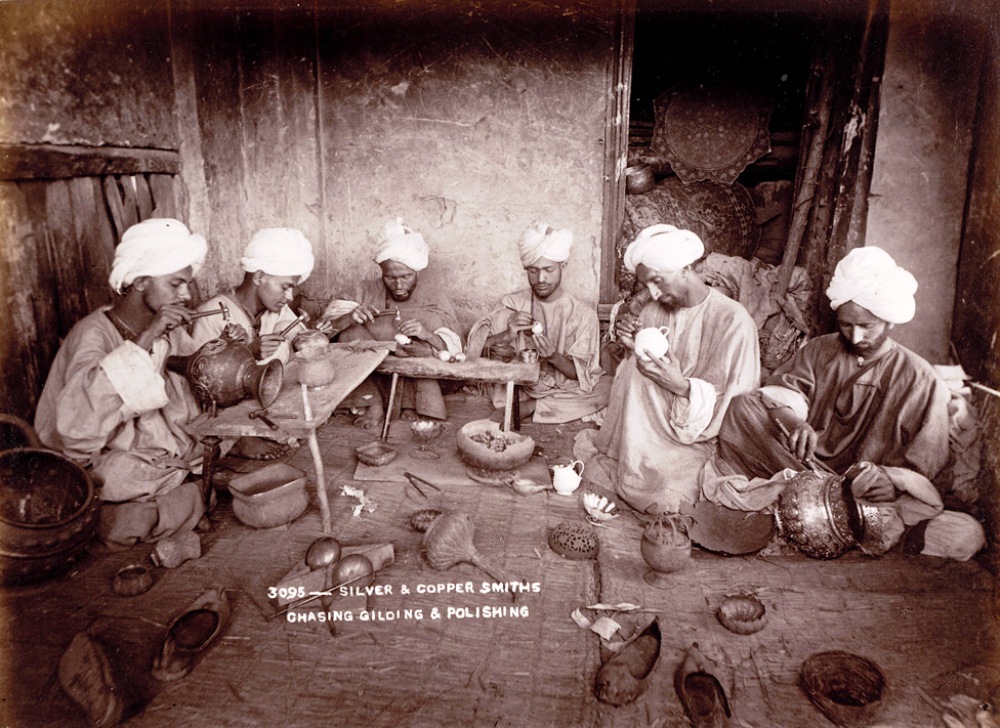

Naqashi: It’s the art of carving copper objects with chisels and hammers to create intricate designs on them. This design is inspired by Islamic art and architecture which feature floral and geometrical designs. It can be seen on a Kashmiri Toor (a utensil which is used to keep the Kashmiri delicacies in), Samovar (urn made of copper) and so forth.

Tracing: It’s the technique of creating designs on a sheet of paper, and then the sheet of paper is traced on a sheet of copper using the stylus. Thereafter the traced piece of copper is carved using chisels and hammers, resulting in a beautiful design.

Embossing: It’s the art of creating designs on copper by hammering it from the back. Some trays bear this technical work on them.

Engraving: This is the art of engraving a copper object with a burin to create a design. Then the design is filled with ink to give it a nice, soothing and cultural look.

Filigree work: It’s a process of twisting and bending thin strips of copper to make intricate designs. Examples of which are some of the ear-shaped handles of trays.

Kalai (nickel coating) is an integral part of a copper object. It’s finally done to the copper object to make it look clean. It’s believed – and backed by science as well – that eating in copperware not coated with nickel causes health issues. As a matter of the acidic foods that the copper is reactive to. That nickel-coating doesn’t let the small remnants of copper creep into the food. In Kashmir copperware was used by Muslims and brass by Hindus. Muslims would go for nickel-coating and Hindus for brush-cleaning.

Expert Speaks

What a copper-smith located at Gaedi-Bazaar, Zaina-Kadal, says about his copperwork:

His name is Ghulam Qadir Baba.. His copper shop is located at Zainakadal. He has been selling and making objects of copper for a long time. Copperwork has been his ancestral occupation. He makes many copper items such as Samovar (a metal urn), Toeer (a small copper item in which Kashmiris keep delicacies), Thalbana (a copper item in which Kashmiris eat rice), Traem-Sarpoosh Tash-Naaer, plates, tumblers, spoons, water-containers and so forth.

Copperwork is no easy task. It needs one to have a strong grasp of the minute details of it. You need to be trained first for a period of 20 years to become adept at crafting such artefacts. Unlike Dairy Farming, copperwork is a profession of skilled people.

Those who make copper objects are called Thanthur. And those who carve intricate designs on a certain copper article is called Naqshgaar. Thanthur is derived from the word Thathyaar, which is used in Persia. This little tweaking to the word occurred due to the local dialect of Kashmir: as in Sulaa (nickname) for Sultaan.

There are several other objects made of either aluminium or steel, challenging copperware and its makers. Be that as it may, copperwork has continued and is fairly preferred by the people so far

In the past, due to the paucity of human innovation, which is to say, machines, Charakhing was done using hands. Machines came later. This sped up the production process and reduced human labour.

However, there is an increase in the number of variegated machines that make copperware. It’s not good. We hammer copper constantly, the machines do it in a single blow. The copperware we make by using our hands are strong.

We should keep this tradition of making copper objects using our hands alive.

Do machine-made copper products pose a challenge to these artisans?

With the passage of time, the number of people engaged in such crafts reduced. It could be attributed to the varying notions of modernity. As Zareef Ahmed Zareef critically mentions, once people get modern education, they forget about their culture and history. All they do is walk with their hands in their pockets. Modernity came with its own pros and cons. By turning eyes completely to machine-based industries, we are threatening our handicrafts. In addition, machines affect our handicrafts and artisans in two ways:

(1) Machine-based industries spike the unemployment rate among artisans. As the goods made from machines take less time and are relatively economical, people seemingly prefer it to the time-consuming investment-heavy hand-made goods.

(2) With the coming of machines, the non-artisans, untrained and unaware of the specifics of copperwork – engage in such a skill-demanding profession. As a result, artisans suffer in ways incalculable: in terms of people purchasing machine-made copperware mentioning them being economical.

Even though the government introduced an act to protect the handicrafts from perishing in 2006, banned machine-made goods, and came up with another policy in 2008, banning and auctioning the existing machine-made goods to the people, such policies aren’t strictly adhered to, and machine-made goods swamp the markets, pointing to the perishing of handicrafts in Kashmir.

The government acts harshly for the time being by implementing policies and acts. With time, the impact of such policies dies down, resulting in negatively impacting the craftsmen.

(The author is pursuing PG in history at Kashmir University. Ideas are personal.)