A young academic has revisited the state of governance in Jammu and Kashmir between 1948 and 1989 and attempted to understand how the conflict (mis)management has led to a sort of a crisis by adding to the region’s instability and converted it into a sort of a volcano, writes Shabir Mir

“What Happened to Governance in Kashmir?” is the question that Aijaz Ashraf Wani, a young academic from Kashmir asks in the title of his work published recently by Oxford University Press. The author does not answer this titular question; infact, he concludes his book with the same question posed as an exclamation: “And well-wishers of humanity would continue exclaiming in pain: What happened to governance in Kashmir!”

Nevertheless, it does not mean that the question remains unanswered. The whole book is rather the exegesis of this very question. And it has to be this way because when it comes to Kashmir there are no straight answers; that is if there are any answers at all.

Post World War-II saw ‘Good Governance’ and ‘Development’ becoming the dominant narrative paradigms in the field of public administration. South Asia saw its decolonization around the same time and the newly established dominions, more or less, adopted the paradigms of ‘Good Governance’ and ‘Development’ as the touchstones of their administrative apparatus and public institutions. The governance of freshly independent countries of India and Pakistan came to be informed by principles of good governance like Constitutionalism, Rule of Law, Equity, Government Legitimacy, Public Participation, Accountability, Inclusiveness, Transparency and other things. Atleast it was expected to be so in theory and how much of this theory was put into practice remains arguable.

The only place in the subcontinent where no such fig-leaf of theory for governance existed was Kashmir. While India and Pakistan enjoyed complete sovereignty and supposedly had the development and upliftment of their masses as the primary national goal and accordingly primed their governing apparatus and administrative machinery, Kashmir was a ‘governance’ perversity borne out of a host of endogenous and exogenous distorting factors where the so-called ‘governance’ had nothing to do with governance per se. And it is this perversion of governance that Aijaz Ashraf Wani realizes, recognizes and recapitulates in What Happened to Governance in Kashmir?”

Among the endogenous factors the author re-states the obvious fact that the state of Jammu, Kashmir and Ladakh is a state of the union of atleast three distinct divisions with disparate social, cultural, historical, economic, political and geographical distinctiveness. Over the years of their forced union, all the three regions have established an intricate power-relationship. Hence any model of governance not only has to react to this power-dynamic but will also be responded by it.

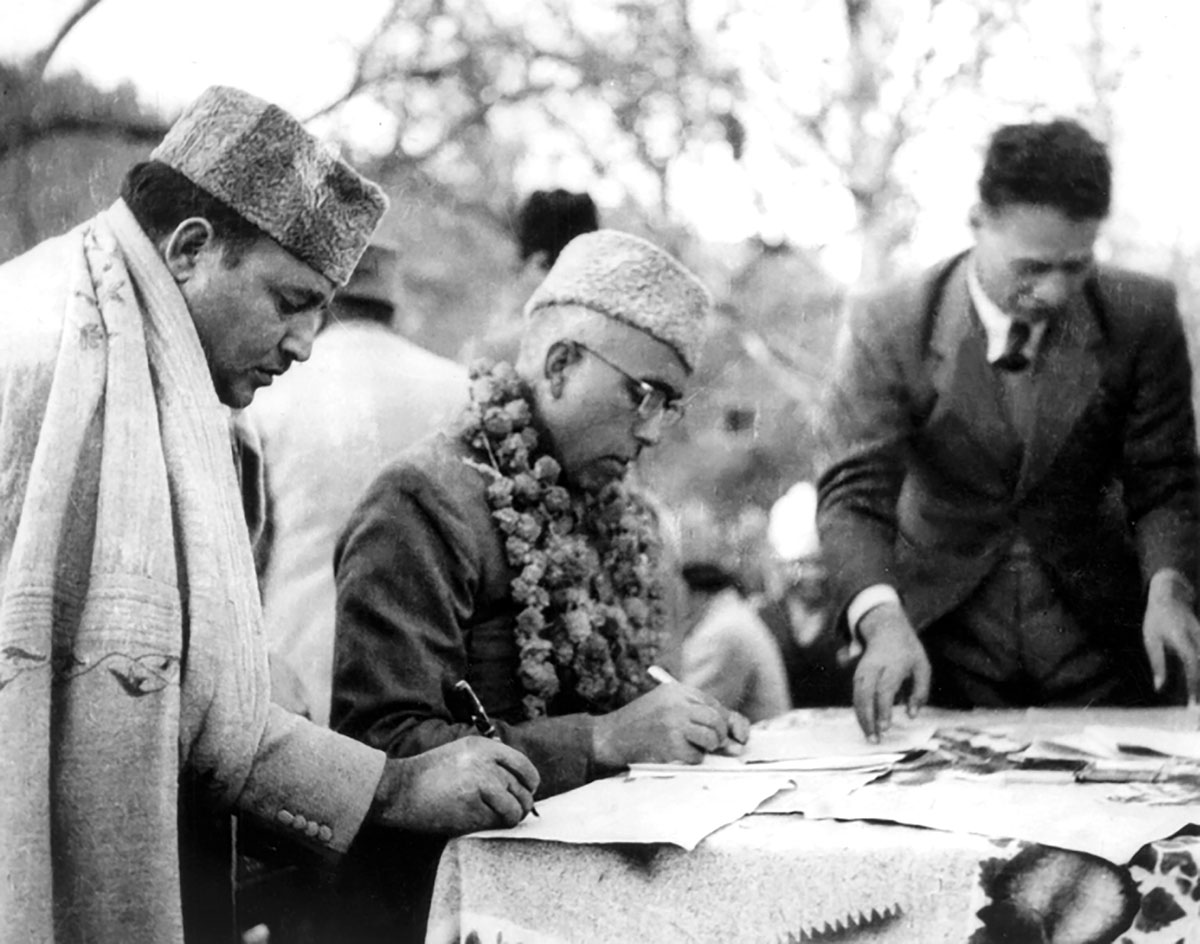

As the author puts it, “A ‘nationalist’ in Kashmiri political discourse becomes ‘anti-national’ in the Hindu and Buddhist political discourses of Jammu and Ladakh and vice versa.” And this face-off leads to an invariable distortion of governance, case in point being the stint of Sheikh Abdullah as the Prime Minister uptill 1953 whose land reforms and anti-monarchy stand rather than being responded to by the public on pure governance principles were responded to by a large section of people from Jammu and Ladakh on the distortion that such governance initiatives caused in the power dynamic between the three regions of the state. And this response eventually, in conjunction with their ideological collaborators and conspirators based in New Delhi, became one of the contributory factors in the downfall of Sheikh Abdullah and by extension Sheikh Abdullah’s Naya Kashmir governance model. And ever since, every governance regime of the state of Jammu and Kashmir had to be wary of disturbing this inter-regional power dynamic.

That being said it is, however, the exogenous factors that have predominantly distorted the governance of Kashmir. Till date, both India and Pakistan claim the territory of Kashmir and within the state of Jammu and Kashmir, the peoples’ choice varies between various permutations and combinations of a merger with Pakistan, complete independent sovereignty and greater autonomy within the Union of India. As a result, Kashmir has been reduced to a state of perpetual conflict wherein every principle of governance and democracy has been sacrificed at the altar of ‘Unity and Integrity of Nation’.

Thus the state government which was meant to be a partner of the Union Government of India in governing the state of Jammu and Kashmir has been reduced to a ‘client government’. In the words of the author himself, “Instability produced a series of consequences, namely, a deficit of peace, intolerance of opposition, denial of democracy, installation of ‘client governments’, and the central government’s collaboration ‘with the political practices, corrupt or otherwise, of their sponsored establishment faction.”

Consequently, governance under such a set up has been transmogrified into a tool of control and subjugation and remains unresponsive to public opinions and demands and in the process has lost its legitimacy, with elections and appointments and decisions reduced to a farce. In the words of Bakshi Ghulam Mohammad, the second Prime Minister of Jammu and Kashmir, as quoted by the author, “If you stick to democratic principles, you will never be able to have peace in Kashmir.”

The deficit of governance thus created fuels for the already raging conflict thus setting up a vicious cycle of anger, unrest and violence. The conflict feeds the governance-deficit and the governance-deficit, in turn, feeds the conflict forcing the author to note that “(Making Kashmir) in the words of Haley Duschinski, the ‘exceptional state’ or the ‘state of exception’.Within the state of exception, the sovereign becomes absolute and unreferenced, requiring neither legitimacy nor legality for eternal justification.‘The state of exception’, writes de la Durantaye, ‘is the political point at which the jurisdiction stops, and a sovereign unaccountability begins; it is where the dam of individual liberties breaks and society is flooded with the sovereign power of the state. Being a disputed/ contested site on which to ‘establish geographical boundaries of the national territory as well as the metaphorical borderline of national identity through social control’, the region has been designated as a state of exception and emergency.”

Speaking overall, the book does not break any fresh ground in the political history of Kashmir but what it rather does is that it grants a stamp of authority and reliability to the oral traditions and narratives by its dint of extensive scholarship and research. It backs the widely held opinions with data and facts duly referenced and annotated. What it misses is an investigation into parallel centres of governance and authority that have found their place in the state of Jammu and Kashmir in the form of religious power centres or subaltern power centres like those held by the separatists within their particular domains. It may be argued that such institutes do not fall under the purview of public governance but in Jammu and Kashmir (as also in South Asia by and large) the lines delimiting public and private are not quite distinct.

All in all, What Happened to Governance in Kashmir? by Aijaz Ashraf Wani is an appreciable and welcome addition to the nascent corpus of the scholarship of Kashmiris’ engaging with their own political history: a worthy addition.

(The book ‘What Happened To Governance In Kashmir’ was published by Oxford University Press.)