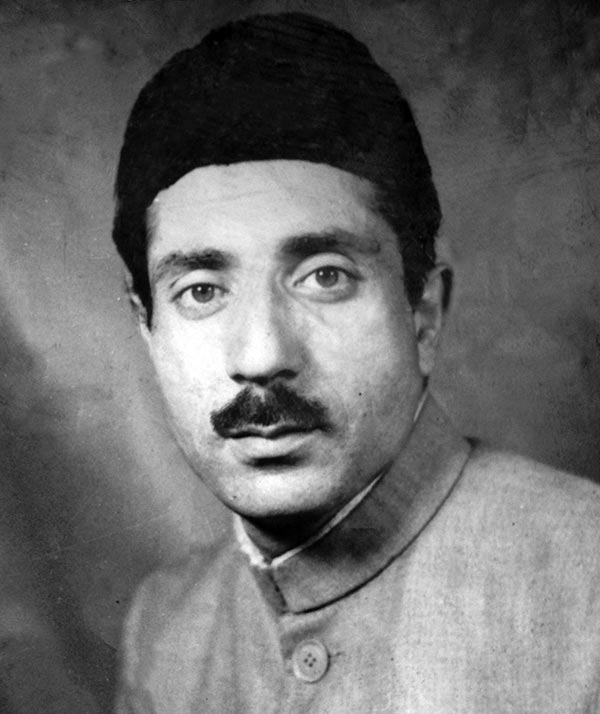

Peerzada Ghulam Jeelani

(1925 – 2016)

By Shams Irfan

Two years back, on a hot June afternoon, I finally met Peerzada Ghulam Jeelani. One of the last remaining members of J&K’s constituent assembly, I wanted to know what happened in 1950s. Three cigarettes and equal number of cup of teas after, Jeelani Sahab finally agreed to talk.

“It was a different era. A different world in fact,” said Jeelani in his frail but authoritative voice. “I am talking about Mahraja’s rule.”

When Mahraja was ruling Kashmir, Jeelani, a teenager then, had his first encounter with Zulm (atrocities). “We owned a few kanals of saffron land at a nearby karewa,” recalled Jeelani. “I remember, a few years before Maharaja fled Kashmir, I accompanied my dad to help him pluck flowers.”

In the evening, after saffron harvest was over, instead of going home, everybody started dividing their produce into two equal halves. When Jeelani asked why they are doing so, he was told that they are following Mahraja’s dictate.

“Unable to do anything, we too made two equal sacks,” recalls Jeelani. Then, like a herd of cattle, Mahraja’s men shooed thousands of men, women, and children towards Frestabal, a small locality on the outskirts of Pampore town.

After more than an hour’s trek on foot, when Jeelani and his father reached Frestabal, they were made to stand in a long queue.

At the end of the queue was a table where an expressionless “contractor” was standing with a stick in his hand. “These contractors were Mahraja’s men,” said Jeelani.

When Jeelani’s father’s turn came, the expressionless contractor gestured him to place both sacks of his saffron produce on the table. “My father obliged.”

Then, the contractor carefully chose the bigger one and tossed it aside among other sacks. “This was Mahraja’s share.”

Before letting them go, both Jeelani and his father was frisked by one of contractor’s henchmen. It was to make sure that they are not hiding flowers inside their clothes.

Then they handed Jeelani’s father the other sack and ordered him to go home. “I felt very humiliated.”

What irked Jeelani most was the fact that nobody, not even kids, were allowed to go home from their saffron fields, unless they get frisked at Frestabal.

That day Jeelani said he vowed that he will fight against this humiliating system.

The moment young Jeelani questioned this exploitative practice, he was branded a rebel by Mahraja’s men. “Rebel, I was,” said Jeelani with a smile, as if he was still young and facing Mahraja’s men.

Jeelani joined Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah, and started advocating for revocation of Mahraja’s exploitative rules. But the taxation on saffron produce ceased only after Mahraja fled Kashmir in 1947.

Jeelani, who did his matriculation from Mission High School, Fatehkadal, (before 1947) considered himself an accidental politician. “I joined politics just to fight Mahraja’s oppressive rule,” recalled Jeelani. “But even after he was gone, the oppression of poor continued.”

In 1951, Jeelani was nominated to constituent assembly from Pampore. “It was exciting. We were finally masters of our own destiny,” recalled Jeelani.

Initially, there was lot of excitement among 75 members. “Like today, we hardly fought inside the assembly. Rather we used to debate on issues concerning people,” said Jeelani. “I still remember how abolition of Jagirdari system was debated. It was part of NC’s Naya Kashmir manifesto. So everybody backed it, but first it was debated.”

Initially, there was lot of excitement among 75 members. “Like today, we hardly fought inside the assembly. Rather we used to debate on issues concerning people,” said Jeelani. “I still remember how abolition of Jagirdari system was debated. It was part of NC’s Naya Kashmir manifesto. So everybody backed it, but first it was debated.”

However, the excitement was short lived as Sheikh Abdullah started calling shorts without consulting anybody.

“The best ruler that Kashmir witnessed in its troubled history so far is Bakshi Ghulam Mohammad,” felt Jeelani, who later joined Congress and stayed loyal to it till he retired from active politics. “Sheikh Abdullah was different. He wouldn’t listen to anybody. He always did what he thought was good. That became reason for defection and ultimately his fall. He was like a dictator.”

Jeelani recalled how, after Mahraja’s accession with India, Sheikh promised them that they will have absolute authority to decide things in Kashmir’s assembly. “Sheikh was warned by Choudhary Ghulam Abbas (Jammu) that he has given away too much,” remembered Jeelani. “He told Sheikh not to surrender everything but he didn’t listen. He never did.”

Jeelani remembered how every NC loyalist remained silent when Sheikh singed Delhi Agreement in 1952.

Before I could have asked him to explain the mood, he lit another cigarette, smiled and said: “You know there was no pay for MLA’s in the early years, rather we used to get Rs 10 as sitting fee whenever assembly was in session.”

Jeelani who represented Pampore for four consecutive terms (1951 to 67), oversaw construction of local Eidghah, formation of Auqaf Trust, renovation and upkeep of 16th century Khankah, and also start of Islamia School. Pampore became one of the first towns to get proper water supply.

My father remembers how waterworks employees once made a garland of taps, with water sprinkling out of them, for Jeelani Sahab to honour him and his contribution. “It was after I won an election against Sanaullah Dar,” recalled Jeelani.

Politics apart, what kept him busy all these years? “I was very fond of Sufiana mehfils (gatherings),” he said. “Being part of these mehfils helped me stay away from corruption. My rehbar was Sulle Sahab-e-Geratsaz.”

Jeelani, who was legislative council member from 1967 to 1972, had spent a considerable part of time in Shopian jail in famous Rambiyaar Case. “Mohiuddin Karra was also one of the 12 accused. But he was not arrested,” said Jeelani. “They used to take us to Srinagar for hearing, but on foot from Shopian.”

On June 28, 2016, after brief illness, Jeelani finally breathed his last. He was 91.