by M J Aslam

A lot has been written about August 9, 1953, removal of Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah from the chair of Kashmir’s Prime Minister. In spite of that, curiosity still fills many minds among pro-and-anti-Sheikh Abdullah to know why he, after helping India, internally as well as externally, in taking Kashmir, was considered a threat to India which led to his unceremonious dismissal as PM on August 9, 1953.

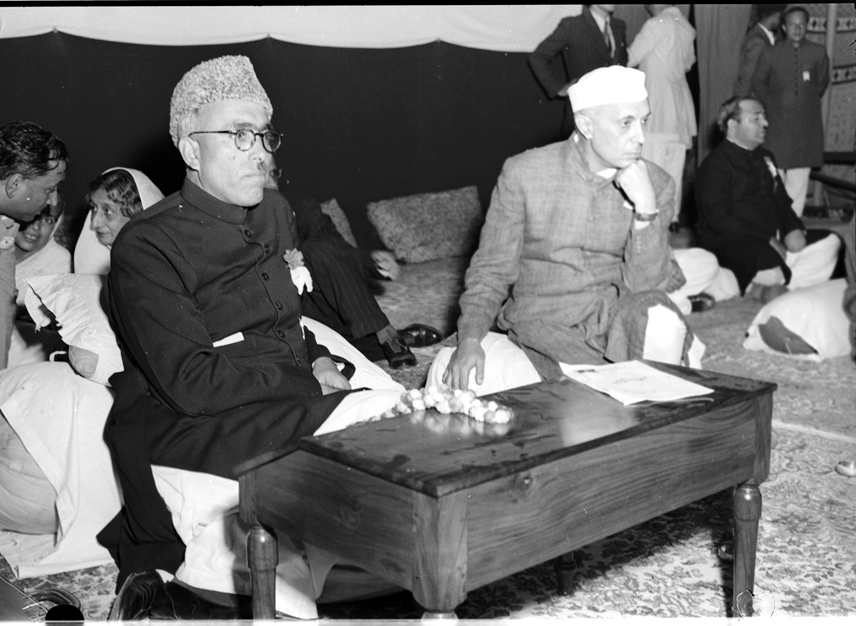

Who on the earth doesn’t know of the deep friendship that existed between Sheikh Abdullah and Nehru during those crucial days of Kashmir’s political history? Nehruvian persuasive skills and mesmerising political nuances unequivocally had an indelible impact on Sheikh Abdullah in setting the direction of his political thought “against the popular sentiment of the majority population of the State”. [Shri Om Mehta Diaries, cited in footnote page 244 of M M Isaaq’s Nida e Haq (2014)]

Nehru-Sheikh bonhomie was indeed responsible for turning the tables on Mohammad Ali Jinnah and his two-nation theory. But it doesn’t answer the curiosity why then Nehru un-friended and sentenced him, so ruthlessly and discourteously? After all, the two were doubtless confidantes or “one soul in two bodies” [Mantu shudam tu manshudi man jah shudam tu tan shudi man degram tu degree, see Times of India dated November 3, 2011: Sheikh Abdullah’s speech at Lal Chowk in 1947] with shared socio-politico-secular outlook. They were not only political colleagues but also close personal friends. [Alan Campbell-Johnson, Mission with Mountbatten (1951) page 10)] What happened then that “proved” Nehru, willingly or unwillingly, “more oppressive and dictatorial than the Maharaja” for him. [Sheikh Abdullah’s The Blazing Chinar (2016) page 188)]

Dismissal of Sheikh Abdullah from the PM-chair didn’t happen by accident. It was connected to a chain of historical events, knowledge and understanding of which will unfold the causes of Sheikh Abdullah dethroning. We will throw some spotlight on that historical background.

Firstly, it has to be noted that after India took Kashmir to the UN on January 1, 1948, quite against its pre-held expectations that the world body would declare Pakistan as “aggressor”, UN held JK “international dispute”, resolution of which was to be got by holding a free and impartial plebiscite under UN auspices. Finding itself caught on a wrong foot by UN Resolutions, India “regretted” its decision. [Ram Chandra Guha, India After Gandhi (2007) page 242)] It wanted to come out of UN tangle which equalled to “unusual and abnormal” conditions in the words of Gopalaswami Ayyangar. [Prof Amitabh Mattoo, Understands Article 370, published in The Hindu dated 6-12-2013)]

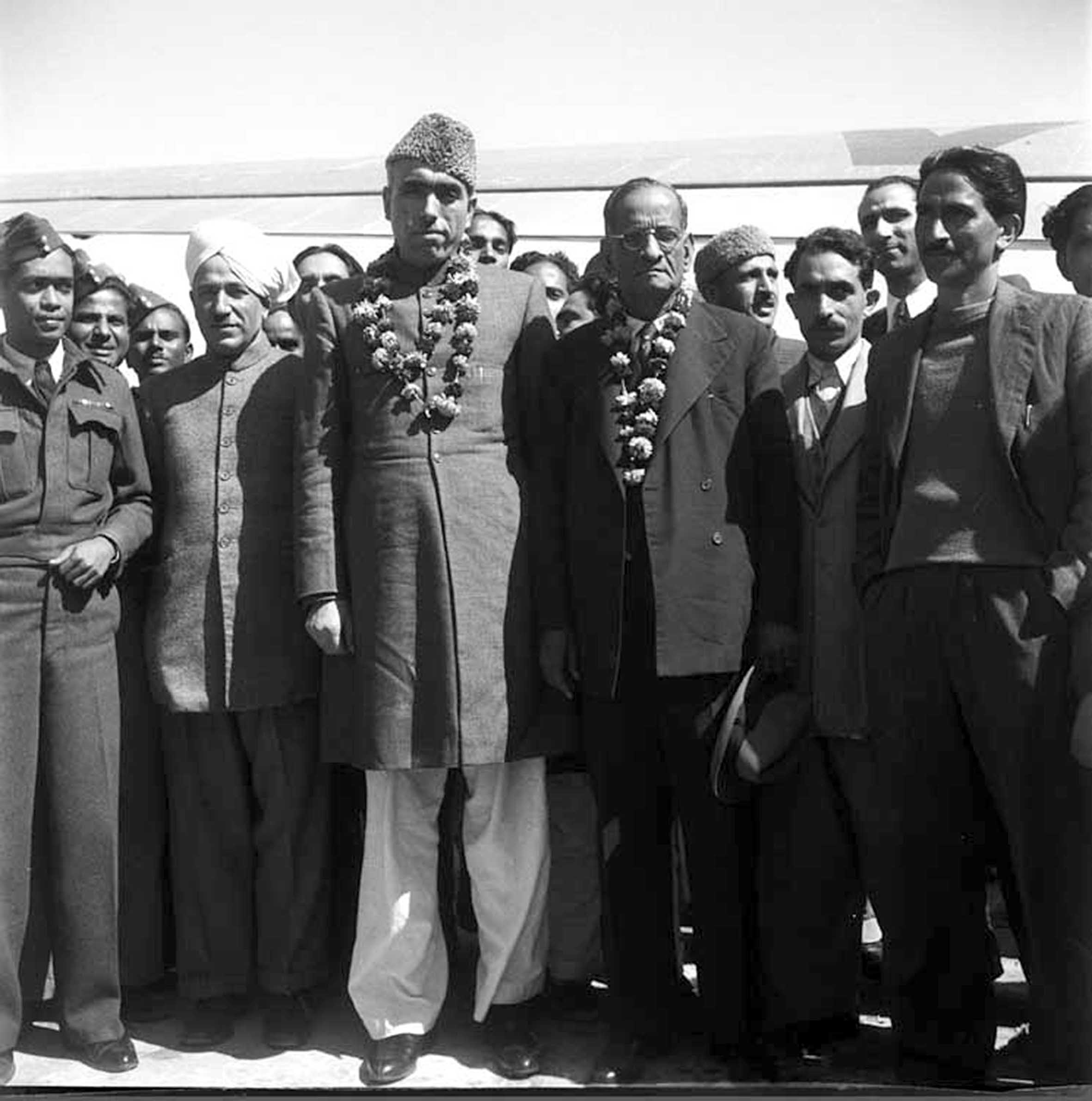

But it wasn’t possible for India to do then as it was the petitioner and signatory to the UN Resolutions, apart from having had publicly conceded, more than once, to the Kashmiris’ right of self-determination. So, it seemingly needed time to procrastinate settlement of K-Issue and someone within Kashmir who could come to its rescue as it had only army control over the land. Who would have been better there than Sheikh Abdullah to do the job? Amid marathon debates in UNGA followed by preparatory steps for conducting a plebiscite, it was Sheikh Abdullah [with his few colleagues, not elected by people but nominated by the party for the job though], at whose request Article 370 was adopted in the Indian Constitution on October 17, 1949.

Article 370 which was the total rejection of NC proposed Article 306-A by S Patel and Gopalaswami Ayyangar [see Gopalaswamy Ayyangar to Patel (letter dated 15 October 1949) page 302; Sheikh Abdullah reply letter to Gopalaswami Ayyangar dated October 17, 1949; Sheikh Abdullah had just threatened S Patel he would resign from the premiership and dissolve State constituent assembly to which Patel replied that was your choice; but Sheikh never resigned on his return to Srinagar, instead he supported accession in full] was a “conduit pipe” employed by them to link Kashmir “constitutionally” with India, which was intending to become a constitutional democracy.

The jubilant architect of Article 370, Gopalaswami Ayyangar, said: “Article 370 will provide the basis for merging J&K with India and, henceforth, Kashmir’s freedom and right of self-determination will be impossible”. [Shabnum Qayoom, History of Kashmir (2014) page 300)]

But Sheikh Abdullah had a different self-pleasing notion about Article 370 that it had made Kashmir a “free country” with power to decide on its internal matters through its State Assembly while the Indian role would be limited to external matters mentioned in IOA only. [J&K CA Debates, page 481)] It was a Faustian bargain of Sheikh Abdullah with India is proven by the fact that through this tunnel (Article 370) the whole of the Constitution was applied to the J & K. [Jagmohan, My Frozen Turbulence in Kashmir, (2006, 7th edition), page 252; AG Noorani, A Constitutional History of Jammu & Kashmir’ page, 2)]

A dispassionate analysis of his statements shows that he actually wanted Pakistan to be kept away from J&K, with no role for UN [even] in K-Issue where it was a pending settlement, and himself as unopposed perennial head of the State after the Maharaja was completely disposed of from the scene, all but with the Nehruvian help. Nonetheless, in total ignorance of the history and geopolitics, he had been playing a most perilous game of politics at most critical times with most formidable politicians of INC. But sadly, “at the end [he] found himself entangled in the web of his own methods and policy”. [Josef Korbel, Danger in Kashmir (1954) page 206)]

Secondly, for some Congress leaders (Patel and Ayyangar) and all right-wing parties of India, the inclusion of Article 370 was not a welcome provision in the Constitution as they saw it an obstacle in the way of total merger of the State with Indian Union contrary to the procedure adopted with other princely States. The right-wing Hindu organisations wanted the State “should be incorporated lock, stock and barrel into the Indian Union”. [Alastar Lamb, Disputed Legacy, page 198] It was thought that Article did not define fully the State’s relation with India. Nehru too wanted Sheikh Abdullah to do more to prove his secular loyalty and credentials of pro-Indian ideology. So, ultimately, he entered into Delhi Agreement on July 24, 1952, with Nehru that declared that J&K shall enjoy certain unique privileges within Union Of India (UOI) which besides conceding a number of powers to the UOI, also included that the State shall have its own Constitution, its own flag besides Indian flag, the head of the cabinet shall be called PM, and the head of the State shall be called Sadr-e-Riyasat who shall be appointed by the President on the recommendation of the State Assembly.

There was an extraordinary reaction to these contents of the Delhi Agreement in particular. The Hindu rightwing parties of Jammu, namely, Praja Parishad, Bhartiya Jan Sangh and Hindu Mahasabha, who had been hell-bent on a total merger of the State with the UOI like other States launched a violent and aggressive movement against the Delhi Agreement in Jammu, Delhi and some other parts of India with processionists and protesters raising “catchy slogans: Ek Desh mein Do Vidhan, Do Pradhan, Do Nishan…nahi chalenge, nahi chalenge (Two Constitutions, two heads of State, two flags…these in one State we shall not allow, not allow) . [Ram Chandra Guha, India After Gandhi (2007) page 249]

This Hindu agitation against Sheikh Abdullah planted seeds of parting his ways with India in his mind as he had started apprehending what will happen to Muslims of J&K after the death of Nehru when communal elements will take over India? [Ibid page 254; M M Isaaq’s Nida e Haq (2014) page 242] Nehru wanted implementation of the Delhi Agreement but could not in the face of furious opposition by the rightwing Hindu organisations.

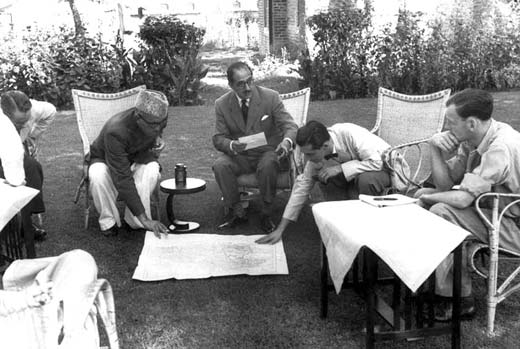

He sent delegates, Abul Kalam Azad and Rafi Ahmad Kidwai, to Srinagar to convince Sheikh Abdullah but he was not ready to listen to them. [M M Isaaq’s Nida e Haq (2014) page 245] In the meanwhile, some American diplomats, Stevenson and Anderson, had called on him at Srinagar and discussed with him about his idea of possible independence, albeit “agencies” [D P Dhar, Karan Singh, G L Dogra, Shyam Lal Saraf, Bakshi, Sadiq, Qasim, B N Mullik, Chinese Betrayal: My years with Nehru (1971) page 37; CJ , M Y Saraf Kashmiris Fight For Freedom (2009) page 1208-09] had been regularly reporting Nehru about Sheikh Abdullah’s activities, [Alastar Lamb, Disputed Legacy, page 190] but his idea of independence was rejected by Nehru saying that independent Kashmir would be a great threat to the freedom of both India and Pakistan [Ibid, Danger in Kashmir, page 242] and that he would rather prefer giving Kashmir to Pakistan on a platter. [Ibid,M M Isaaq, page 245, footnote]

Earlier on January 28, 1948, US Representative, Ambassador Warren Austin, had also made it clear to Sheikh Abdullah that “independence was not an option on offer. The only question before the Security Council was whether Kashmir should go to India or to Pakistan”. [Alaster Lamb, Birth of a Tragedy, pages 142-143]

Thirdly, under the aforesaid circumstances, especially Hindu rightwing campaign, “temporarily” though shook his faith in secular concept about Indian State, and aroused a wave of criticism and despair from many workers within his party against his signing of the Delhi Agreement [CJ, M Y Saraf Kashmiris Fight For Freedom (2009) page 1204] who saw it as “further erosion” on autonomy and freedom of the State. These developments naturally upset Sheikh Abdullah. [Supra, Shabnum Qayoom, pages 373-380] So, he had to hurriedly convene a meeting of his party workers to “favourably” interpret its provisions to calm the rising emotions down. [Supra, CJ, M Y Saraf Kashmiris Fight for Freedom] He then began openly venting his spleen on Kashmir’s relation with India.

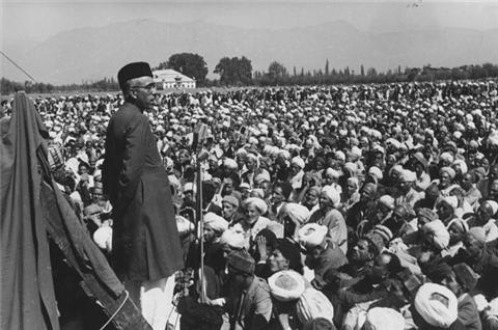

It culminated on July 13, 1953 (Martyrs’ Day) into his emotional outbursts at huge public rallies at Naqshband Sahib Shrine, Jamia Masjid and Shahi Masjid which he attended one by one and where he repeatedly declared: “I regret my mistake of coming in the way of a merger with Pakistan. I had fears they won’t treat me well, but I was wrong. Now I feel back-stabbed, I no longer trust Indian rulers, we have different ways now”. [Greater Kashmir dated August 9, 2016; M M Isaaq, pages 249-251]

Earlier on April 10, 1953, Sheikh Abdullah had spoken at a public rally in RS Pora Jammu that communalism had not finally been buried in India and that its presence there till now makes J&K Muslims highly worried and apprehensive to think of all eventualities and possibilities. [Satish Vashishth’s Sheikh Abdullah Then and Now, (1968) 88]

On July 25, 1953, Sheikh Abdullah said on the impact of Praja Parishad agitation: “The confidence created by the National Conference in the people here (regarding accession to India) has been shaken by the Jana Sangh and other communal organization in India.” [Ibid, page 97]

Naturally, such change of the political outlook of Sheikh Abdullah was not liked by Nehru and other INC leaders. So, from all this, it is not difficult to see why India found it expedient to remove him from his post of the local premiership. [Alastar Lam, Birth of a Tragedy, page 143]

Fourthly, removal of Sheikh Abdullah would not have been so difficult for “Delhi rulers” but they must have been extremely anxious about how to face international community as the issue was very much alive in the United Nations? But panacea to all growing difficulties and anxieties at this moment for India came from a group of “insiders”, cabinet ministers, Bakshi Ghulam Mohammad, S L Saraf, D P Dhar, and others, intimately close to Sheikh Abdullah, who had been prepared by Nehru for the task as a special group and who were acting in unison with Karan Sigh and B N Mullick. Bakshi topped the list of this new group of special loyalists and hence, was sworn in as new local premier once Sheikh Abdullah was removed and arrested on August 9, 1953, at Gulmarg under the directions of Nehru on the pretext of that Sheikh Abdullah had established liaison with Pakistan Government, [Supra M Y Saraf Kashmiris Fight For Freedom, page 1211-1212] had waged a war against Indian State by talking of “independent” Kashmir and had lost the support of his cabinet. He was, however, “denied” to prove his majority on the floor of State Assembly.

Later in 1958, he was “framed” under bogus “Kashmir Conspiracy Case” without any trial. The case was withdrawn in 1964 as “political decision” but a lot of damage was already caused to State’s autonomy through Bakshi and his successors in office till 1975 when Sheikh Abdullah finally decided to rejoin mainstream politics of India and once again occupy the chair, not of PM but of CM this time.

Tail Piece

The story of Sheikh Abdullah is a sad and sorry one. It is the story of once a patriot, a fighter, then turning into an opportunist and, worse, a dictator who at the end found himself entangled in the web of his own methods and policy. [Josef Korbel, Danger in Kashmir (1954) page 206]

Postscript

It may be added here that some people wrongly assume that the removal of Sheikh Abdullah was linked to his land reforms legislation. Historically Sheikh Abdullah factually, it had nothing to do with that. Had it been so, then, immediately after enactment of the Big Landed Estates Abolition Act, 1950 that abolished Jagirs mostly of royal descendants of Dogras, Sikhs and Pandits, there would have been Praja Parished-Jan Sangh type agitation against it. It did not bother Indian leadership or “communal parties” at all since they were focused on “higher planning” of geo-politics to annex Kashmir with India.

(Views expressed here are personal & not of the organisation the author works for. M J Aslam is author, academician, story-teller and freelance columnist. Presently AVP, JKB. The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author’s and do not purport to reflect the opinions or views of Kashmir Life.)