The ongoing Sino-Indian tensions are primarily focussed around Daulut Beg Uldi, a high mountain plateau almost equidistant to the Karakoram Pass and the Akshi Chin. Home to world’s highest airstrip, built during the 1962 war and subsequently abandoned till the army revived it in 2013 and successfully landed a Lockheed Martin C-130 J-30 transport aircraft, this is one of the last outposts in the inhospitable region. The army invested hugely in the 255-km long Darbuk Shyokh Daulat Beg Oldie (DSDBO) road, an upgrade over an earlier alignment that lacked dependable bridges. Galwan Valley heights, the other spot where the bloody brawl took place, is overlooking the movements on this road.

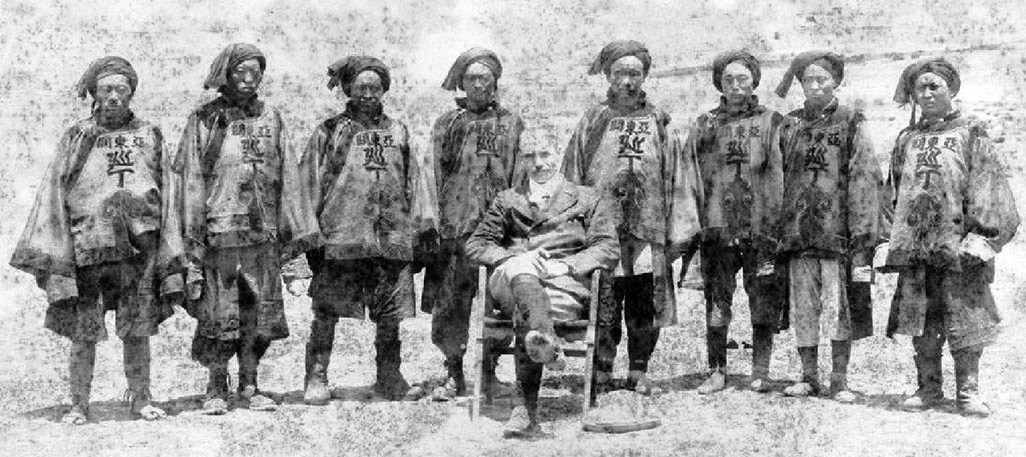

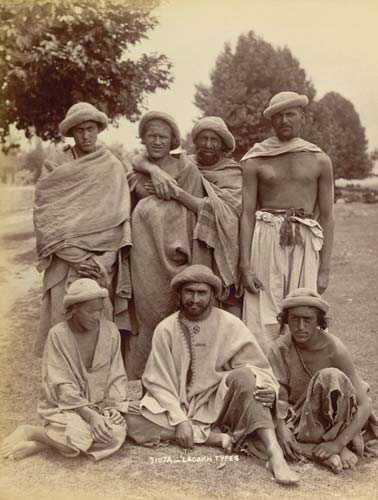

In this long piece, written by British India’s army surgeon explorer, Henry Walter Bellew (August 1834 –July 1892) after his return from the Second Yarkand Mission, the India born British doctor offers a narrative about what the Daulat Beg Uldi is and why it is named after a Kashgar ruler whose uncle ruled Kashmir for a decade before being killed. Aimed at meeting the Kashgar king, Yakoob Beg, the Mission at the peak of Great Game envisaged Thomas Douglas Forsyth, John Biddulph, Ferdinand Stoliczka (who died not far away from DBO) Thomas Edward Gordon, Henry Trotter, and RA Champman. Maharaja Runbeer Singh had made elaborate arrangement for the mission between Muree and Shahidullah by deploying two senior officers and arranging 1621 horses and yaks and 6476 coolies of whom 1236 were palanquin bearers.

From Gyapthang we marched to Daulat Beg Uldi, fifteen miles. The route goes up the river a little way, and then crossing a wild tract of gravelly hillocks, drops into a tributary channel. From this, it rises on to a wide and bleak plateau, which forms the table-land of the Caracoram range. On this plateau we camped, under the shelter of a gravelly bank that limits the bed of the stream which flows down from the Caracoram pass, whose range of black gravel and shale, as the name imports, rises in the fulness of its nudity and desolation right before us.

As we turned away from the main stream of the Shayok, we left behind us a magnificent panorama of glacier scenery, but a touch of the cold wind streaming off from it made one shiver, and think what it must be in winter. Yet a month later this will be the route preferred by the venturous traders who travel this way, owing to the severity of the dam on the Dipsang route.

Away to the left, at about six miles off, the Shayok is lost in the vast field of glaciers from which it issues.

These come down in three main lines from the north-west, and south-west, and unite in one great mass, which fills the wide plain into which the river bed here expands. They appear like rivers set solid in a coating of purest white, and slope down for twelve or thirteen miles from the foot of the lofty snow peaks whence they start. And where they meet they present a vast sea which appears as if suddenly frozen solid in the tumultuous foam of its clashing waves; for here the glacier is thrown into a confusion of billowy projections formed by the crashing of the ice under the lateral pressure of the solid streams meeting from opposite directions.

At Daulut Beg Uldi we were rejoined by Mr Johnson with the main camp. He lost two of his ponies in crossing the Dipsang plateau (our first losses), but brought all his followers over in safety. The Dipsang plain is the highest part of this plateau, and swells up to the south of our position, closing the view in that direction. We crossed it on our return journey, as I shall have to mention in its proper place.

The elevation at Daulut Beg Uldi is about 16,000 feet. It is a singularly desolate and bleak plateau, at this season bare of snow, but set about by low ridges and mounds of loose shales, from 18,000 to 20,000 feet high, on which last year’s fall still lingers in thin patches. A very destructive wind is said to blow over this region at times. Fortunately, we escaped it, and had only to put up with the evils of a half ration of our wonted supply of oxygen.

Many of our party here were quite prostrated and appealed to me for relief. “My good man,” I said to each as he gave way to the over powering feeling of careless despair, “your case is no worse than my own, or that of a dozen others about you. Here! Take this salt and put a pinch of it in your mouth now and again, and just put your head on a stone and lie still till the bugle sounds the march.”

There was nothing more to be done. Perfect rest of mind and body I found were the best remedies, though not always attainable. Even when quietly seated writing, I found my pen every now and again jerked forward by an involuntary sudden gasp to fill the chest and raise the load pressing it. And worse, just as I was going to sleep in the hopes of forgetting the pain that racked my head, and the nausea that well-nigh floored me, I was started up by a sense of immediate suffocation. A few deep but unsatisfying gasps and a reeling giddiness brought my head on the pillow again to doze dreamily a while, only to start up afresh and go through the same process over again, and so on till the bugle bade me rise. The exertion of dressing – a luxury I henceforward carefully denied myself till we got down to a dressing level – well-nigh finished me, and it was as much as I could do to mount my horse.

I ate about three drachms of chlorate of potash on the way up, and at the crest of the Caracoram felt quite well, and alighted to take the altitude. It was thus that I, and many others of our party, passed this wretched time on the plateau of the Caracoram.

I was much amused in the midst of these very unpleasant symptoms by the querulous grumbling of a hardy Afghan, who allowed his sufferings to gain the better of his self-control. He had joined our party in Kashmir as a mule driver, and came to me here in a very woebegone state, complaining of his head, and stomach, and limbs, and in fact was dissatisfied with everybody and everything. A frame of mind excusable under the circumstances. “I always gave you people credit for undoubted wisdom,” he said; “but what on earth has brought you to this God-forsaken country, which even these mean Bhots don’t care to inhabit?”

“Come!” I said, “you ought not to complain, for you are accustomed to hills in your own country, and should feel quite at home here.”

“You are perfectly right, sir,” he replied.”We have hills in our country, and proper hills too, with trees on them, by the blessing of Providence. They are ten times higher than these miserable mounds of gravel, and we go up and down them without the smallest discomfort or trouble.”

“Well, my good fellow,” I interposed, “so much the greater reason for your going up and down these small heights without making such a fuss.”

“It is not the height I complain of,” he continued.

“It is the cursed air of the place. Everybody knows it’s poisoned, and what I ask you for is its remedy. There must be something in all those bottles there (pointing to the medicine chest) to counteract it.”

I gave him some of the salt and enjoined rest, and he went off to his place, saying, “Yes! I’ll take this, and, please God, it will cure me. But this dam is a poisonous air, and rises from the ground everywhere. If you walk ten paces it makes you sick, and if you picket your horse on it, it spurts from the hole you drive the peg into, and knocks you senseless at his heels. What else can you expect of such a place? Did not Daulut Beg die here?”

Daulut Beg Uldi “The Lord of the State died,” is the eloquent record of an interesting historical event which singles out this spot from the broad monotonous “waste of this lonely and inhospitable region to perpetuate its memory by the impress of a name foreign to the locality and only suggestive of its character by its expressive termination. This appears to be in accordance with a predilection of the Yarkandis for designating the more fatal parts of the regions they occupy, by the names of those notable personages who may have perished on them. And thus we find isolated spots, otherwise nameless, entitled with a designation commemorative alike of a close to the career of some important individual, and of the ominous character of the locality. Such are Rahman Uldi, Marjan Uldi, Culan Uldi, and others.

The Daulut Beg who has given this spot its name was the Sultan Sa’id Khan Ghazi, who acquired the final distinctive title so honourable to Musalmans by the Ghaza or “Crescentade” upon Tibat – in the progress of which he died – as I have before related on the authority of the Tarikhi Rashidi.

From that interesting and most valuable record of the history of the Mughal Khans of Kashghar, I derive the following brief account of this Sultan Sa’id who, after passing the Sakri or Saser glaciers on his return homewards, was hurried on in a moribund state across the Dipsang plain to expire on the spot indicated by the royal title of the Mughal Khans – a title which is still borne by the present Capchac ruler of the country in the Persianised form of Bedaulat. The new associations of the spot, too, are not without a mournful interest to us; for it was on the passage of the fatal

Dipsang plateau, from the opposite direction, that our lamented comrade, Dr F Stoliczka, succumbed to the hardships of the elevation, and at Murghi, on its hither side, closed too soon a life of invaluable benefit to the cause of natural history and geology.

When Wais Khan was killed – somewhere near Isigh Kol on the upper course of the Chui river – in action against the troops of Mirza Ulugh Beg of Samarcand, he left two youthful sons named Yūnus and Eshan Bogha. They were immediately set up as rival claimants of the throne by opposite factions of the nobles.

Those who adopted the cause of Yūnus, then a boy of twelve years, took him to Ulugh Beg to enlist his favour on his behalf, but he sent the young Mughal prince out of the way to his father Shah Rukh at Herat, where he was placed under the charge of a noted scholar of the times – one Sharifuddin Ali Yazdi – to be educated.

He remained there for twelve years till the death of his tutor, and then went to reside at Shiraz in Persia, till his recall to his own country twelve years later.

Eshan Bogha in the meantime floated about on the waves of anarchy till he was finally cast aside amongst the Kirghiz and Calmac on the north-east borders of the country. But during the period of anarchy in Kashghar, he so repeatedly raided the Tashkand and Farghana territories, that Abú Sa’id Mirza recalled Yūnus from his exile, and set him to recover the government from his brother, and reduce the divided Mughals to order.

Yūnus found the country divided amongst a number of rival rulers of whom he could make nothing, and after repeated disasters, finally succeeded in establishing himself at Tashkand as a protegé of Samarcand, and with only a doubtful authority in Kashghar, still divided amongst rival chiefs.

On his death, Yūnus left two sons, named Mahmūd and Ahmad. Mahmūd succeeded his father at Tashkand, where he had grown up in his court; whilst Ahmad, separating from his father, established himself on the shores of Isigh Kol as ruler of the nomad Kirghiz, and, by his reckless destruction of life, acquired the historical title of Alaja, “The Slayer.”

He made an unsuccessful attempt to wrest Yarkand from Ababakar, and then went to the support of Mahmūd at Tashkand, who was hard-pressed by the Uzbaks under Shahibeg Khan or Shaiban. Both brothers, however, were defeated, and Ahmad, retreating to Acsu, died there that same winter, 1453-4, whilst Mahmūd betook himself to the steppes to try and secure the government of the nomads. He failed, however, and after five years of varying fortunes returned with his family to Tashkand, and sought the protection of Shaiban. But that conqueror, considering him a source of mischief, summarily executed him and all his family by drowning them in the river.

Ahmad left seventeen sons, of whom Mansur was the eldest, and with Sa’id, Khalil, Ayman and Babajac, figured most prominently in the events of the country; whilst Chin Tymur, Bosun Tymur, and Tokhta Boca and other sons joined Babur in India and disappeared from their native land.

With this introduction we come to the career of Sultan Sa’id. At the age of fourteen years, he accompanied his father when he went to the aid of Mahmūd. In the fight that ensued he was wounded in the hip, and taken prisoner at Akhsi; but in the following year he was liberated, and taken by Shahibeg to Samarcand, as a noble attached to his court. Shortly after, however, when the Uzbak chief set out on his campaign against Khiva, Sa’id effected his escape to Mugholistan, and joined his uncle Mahmūd, who was then at Yatakand.

From this he proceeded to join his brother Khalil, who ruled the nomad Kirghiz, and stayed with him four years. During this period, Mahmūd on one side and Mansur on the other contested the government in the steppes with the other two brothers. Finally, Mahmūd relinquished the game, and retired to Tashkand to meet the fate mentioned; whilst Mansur, finding the field abandoned, drove his younger brothers out of the country, and subjugated the Kirghiz to his own authority, transporting their principal camps to Jalish and Turfan.

Khalil and Sa’id now followed in the track of their uncle, but only arrived at Akhsi to hear of his death, and to be themselves arrested. Khalil was summarily executed by Jani Beg, the uncle of Shahibeg, for an attempt to escape. Just after this Jani Beg was thrown from his horse and injured his head, and Sa’id being at this juncture brought before him for his orders he gave him his freedom.

Sa’id at once collected his few followers, and disguising themselves as darveshes, students, and merchants, set out with them from Andijan across the mountains to Caratakin and Badakshan, where he sought shelter in the little fort of Zafar, near the present Panja, and received such hospitality as its owner, Mirza Khan, could afford. For he had been deprived of the fertile valleys to the west by the Uzbaks, and of the highlands to the east by Ababakar, and now led an isolated existence amongst the heretic shias of the place, struggling for the bare necessaries of life.

After a stay of eight or ten days, Sa’id and his fifteen companions set out in miserable plight, with barely a blanket each to protect them from the cold, for Kabul, and on arrival there he was well-received, and taken into service by Babur. He stayed here three years, and on the death of Shahibeg at Marv, in action against Shah Ismail of Persia, he accompanied Babur in his attempt to secure Samarcand.

As soon as Babur had taken Cunduz he sent Sa’id with some other nobles to secure Farghana, which, on the downfall of Shahibeg, had been seized by Sayyid Muhammad Khan, the governor appointed by Yūnus.

And on arrival there, in 1510, he assumed the government from him. On the defeat and flight of Babur from Samarcand, Sa’id continued to hold Farghana, and in the spring of the following year set out to visit Casim Khan (son of Jani Beg), the chief of the nomad Cazzac, with a view to effecting an alliance with him on terms of equality. His efforts failed, however, and after enjoying a brief indulgence in cumis on the free spread of his native steppes, he returned to Farghana to wait events.

Meanwhile he repulsed an attempt made by Ababakar to annex the province. But on the return of the Uzbaks two years later, and the fall of Tashkand to their hordes, Sa’id retired from Farghana to Mugholistan, and from there, whilst the Uzbaks under Suyunjuk were ravaging Andijan, he made a descent upon Kashghar, where Ababakar’s frightful oppression had rendered him hated.

Sa’īd drove Ababakar out of the country, and after a campaign of three months, mounted the throne at Yarkand in 1513. In the ensuing winter he met his brother Mansur at Acsu, and recognising his rights of primogeniture, consented to share the country with him; Mansur ruling over the eastern half from Acsu to Khamil or Camol, and Sa’id over the western half up to Andijan.

In the following winter, Sa’id essayed to make good his authority over Andijan, but on arrival at the frontier, finding his troops unequal to the task, he diverted his purpose to a hunting excursion on the upper course of the Narin, and returned to his capital in the summer.

He next turned his attention to his southern frontier, and set out on a campaign to convert the pagan Sarigh Uyghur who occupied the country between Khutan and Khita. His intemperate habits, however, frustrated his pious resolves, and he was brought back from Khutan in a stupid state of drunkenness, whilst his troops overran the country of the pagans for two months without ever meeting one of its inhabitants.

Following this he was called upon by the Uzbaks to restrain the inroads of his Kirghiz upon the Tashkand frontier, and sent his infant son Rashid with Mirza Khan (my author) to settle these unruly nomads. He failed to do so, and in the following year, Sa’id himself carried an expedition up to Isigh Kol, and dispersing the Kirghiz returned to Yarkand, leaving Rashid to hold the country.

He next, in 1518, made an expedition into Badakshan to support the authority of his governor, whom he sent to hold the country as part of the possessions he had conquered from Ababakar; and on his return thence, in the summer of the following year, he went to Acsu to meet his brother Mansur, and arrange for the restoration of the place from the state of ruin to which it had fallen after its plunder by Ababakar; and on this occasion recognised Mansur in its government.

Two years after this he again went to Mugholistan to check the inroads of his Kirghiz upon the Uzbak borders, and in the midst of his troubles and intemperance, was seized with a fit of remorse for his misdeeds, and proposed to abdicate in favour of Ayman, the maternal brother of Mansur. The priests, however, interfered to dissuade him from this purpose, so he returned to his capital, and established Ayman in the government at Acsu.

Then, in 1523, he again made an expedition into Badakshan to seize the country from the retiring Uzbaks, but finding it already in the possession of one of Babur’s sons, and the passes behind him closed, he wintered there, and in the spring returned home re-annexing the eastern half of the country to Kashghar “for ever.”

On his return from this expedition he was once more called to the aid of Rashid in Mugholistan, who was now pressed by an invasion of the Calmac. When Sa’id arrived at the Narin river he heard of the death of Suyunjuk in Andijan, and the confusion of the Uzbaks, so he immediately turned off to recover Andijan. He seized Uzkand by coup, and, the people opening its gates, he took possession of Andijan, and annexed the province to Kashghar.

Sa’id now returned to Kashghar to rest awhile from his labours, and, in the interim, in 1527, sent Rashid and Hydar on a ghaza against the kafiristan of Bolor between Badakhshan and Kashmir. The crescentaders appear to have found the savage infidels more than a match for them, and returned without having effected much, though Mirza Hydar gives a most interesting account of their customs and country.

On return from this expedition, Rashid was appointed Governor of Acsu, and six months later Sa’id set out on that campaign against Tibat which I have before mentioned. His biographer (Hydar) says he was a mild and just prince, and during the last years of his reign led a strictly religious life; and with a curious illustration of what his idea of the import of the words are, adds that under his rule the country flourished, and peace reigned from Khamil to Farghana.

(The passages were excerpted from Kashmir And Kashghar – A Narrative of The Journey of The Embassy To Kashghar In 1873-74 by H W Bellew published by Trubner & Co in 1875.)