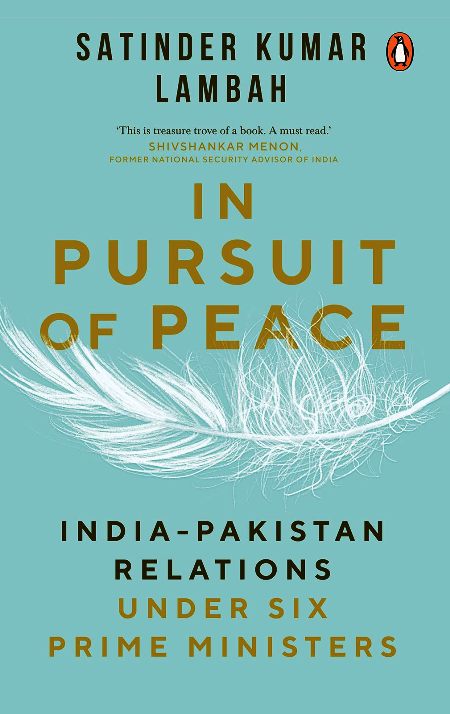

Satinder Kumar Lambah has been the most respected Indian diplomat who worked on India-Pakistan bilateralism. Muhammad Nadeem goes through his memoir which was published months after his death

In the realm of diplomacy, navigating challenging situations is at the core, and Satinder Kumar Lambah, a seasoned diplomat, exemplified this throughout his illustrious career. His adeptness in handling delicate matters led him to be repeatedly entrusted with the task of representing India’s interests.

A significant portion of Lambah’s five-decade-long tenure in public service revolved around engagements with Pakistan. He served at the Indian mission in Islamabad, assuming leadership roles for several years, and played a pivotal role at the PAI (Pakistan-Afghanistan-Iran) desk in the Ministry of External Affairs in Delhi. Additionally, he spearheaded backchannel discussions during high-profile incidents, including the Parliament attack, the embassy bombing in Kabul, and the Mumbai terror attack.

Lambah’s expertise made him the go-to person for numerous governments seeking guidance in dealing with Pakistan. From the 1970s to 2014, he closely observed six prime ministers engaging with Pakistan. Devoting a chapter to each of these prime ministers—Indira Gandhi, Rajiv Gandhi, PV Narasimha Rao, IK Gujral, Atal Bihari Vajpayee, and Dr Manmohan Singh—Lambah delves into the intricate dynamics of the relationship, unravelling the twists and turns that have accumulated over time.

What emerges from this account is a notable aspect of how these prime ministers, particularly Rao, Vajpayee, and Singh, aimed to build a national consensus on India’s Pakistan policy by actively involving the Opposition. This stands in stark contrast to the current political landscape, where the Modi government seldom seeks consultation with the Opposition.

For instance, Rao entrusted Vajpayee with leading the Indian delegation to the UN Human Rights Commission in Geneva. During the backchannel talks under Singh, Lambah maintained constant communication with Vajpayee, who served as the leader of the Opposition in both the Lok Sabha and the Rajya Sabha, ensuring they were well-informed about the ongoing discussions.

Cracking the Code

While cynicism surrounding the dialogue between India and Pakistan is understandable, one of the most experienced individuals well-versed in India’s dealings with Pakistan argues against the unwise decision of disengagement. He paints the neighbour as a strong antagonist to India – their expanding nuclear weapons arsenal, and the worsening stability in the region. Lambah, known for his non-hectoring demeanour, conveys this pointed critique of the Narendra Modi government’s ‘terror and talks cannot go together’ strategy in the penultimate paragraph.

As anticipated, the Modi government has displayed minimal interest in pursuing backchannel talks, rendering Lambah’s efforts futile. He concludes with a cautionary note on the talks between India and Pakistan, emphasising how both nations primarily view each other through the prism of religion. Painful memories of the partition era are being revived, while the lack of contact and regular engagement has resulted in a new generation of youth in both countries who form perceptions solely based on media and social media. This only serves to solidify positions and further widen the divide between our nations—a tragic outcome for two peoples who were once united and still share much in common.

Lambah’s posthumously published book, In Pursuit of Peace: India-Pakistan Relations Under Six Prime Ministers, offers pick and choose insights into the various channels employed since the Simla Agreement of 1972, presenting a chronicle of decades-long failures to establish a modus vivendi for peaceful coexistence between the people of both nations.

The book highlights some notable milestones in India’s journey, such as the initiation of the Delhi-Lahore bus service in 1999, Prime Minister AB Vajpayee’s historic visit to Islamabad in 2004, General Pervez Musharraf’s momentous trip to India in 2005, and the near reopening of consulates in Mumbai and Karachi. However, the present reality paints a strikingly different picture, with no direct flights, scarce visa issuances, the absence of bus services, and the discontinuation of train services between Attari and Lahore. The Khokrapar-Munabao rail route also remains closed, further deepening the existing divide.

Lambah skilfully implies that the ongoing hostilities between India and Pakistan have been exploited for political gains. “We see each other principally through the prism of religion. The painful memories of partition are being revived,” he wrote. This observation reflects the current state of affairs, highlighting how hatred has become India’s prevailing political philosophy, rendering any form of communication or negotiation ineffective.

From Shadows to Spotlight

Joining the Indian Foreign Service in 1964, Lambah occupied himself in the complexities of India-Pakistan relations ever since the partition of the subcontinent.

During his tenure, Lambah played a critical role as a tool for then-Prime Minister Rao to navigate pressure and overcome challenges from Pakistan. The memoir includes various anecdotes from that period, one of which recounts how a delegation led by opposition leader AB Vajpayee successfully thwarted a Pakistan-backed resolution condemning India for human rights violations in Kashmir during a 1994 UN Commission on Human Rights session in Geneva. Lambah reveals that India’s favour turned during a visit to Tehran by Rao’s ailing foreign minister, Dinesh Singh, where he met with the Iranian president and the Chinese foreign minister.

Lambah was also a confidante of I K Gujral, who served as the foreign minister before becoming the prime minister in 1997. Lambah shares insights from Gujral’s diaries, made available by his family, to shed light on an infamous visit by the Pakistani foreign minister, Sahabzada Yaqub Khan, in 1990. During that visit, Khan allegedly threatened to use nuclear weapons despite Pakistan not being a declared nuclear weapons state.

Lambah emphasises that India’s engagement with Pakistan cannot be separated from its internal policies in Kashmir, a perspective acknowledged by Vajpayee and former Prime Minister Manmohan Singh. Their Pakistan policy included initiatives related to Jammu and Kashmir. However, the complete reversal of this thinking since 2014 has not brought peace to Kashmir or stability in Indo-Pak relations.

Former Jammu and Kashmir governor Satyapal Malik recently referred to Modi as “ill-informed” about Kashmir in an interview with The Wire. In February 2019, as disclosed by former US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, the two countries came “too close” to a nuclear exchange.

This situation is neither sustainable nor sensible.

The Kargil War

Regarding the Kargil conflict and the intrusions by Pakistani troops, Lambah absolves Sharif, the prime minister at the time, and the civilian leadership of any knowledge about these developments. According to Lambah, citing Pakistani journalist Nasim Zehra, Sharif was only briefed on the operation on May 17, 1999. However, what followed afterwards, though significant, has been largely forgotten. Back-channel negotiations between the two countries, facilitated by Pakistan’s foreign secretary Niaz Naik and the Observer Research Foundation’s RK Mishra, began in June. India aimed for Pakistan to retreat from Kargil, while Pakistan desired talks on Kashmir.

Lambah states that India conducted an internal study and concluded that discussions could proceed based on a formula and a speech given by Manmohan Singh in Amritsar on March 24, 2006. Singh’s speech laid out basic guidelines, emphasising the need to find pragmatic solutions to the Jammu and Kashmir issue without redrawing borders. Singh proposed ideas such as free movement across the Line of Control (LoC), joint mechanisms for consultation and cooperation in socioeconomic development, and the utilisation of common resources for the benefit of the entire region. Although both leaders avoided the territorial issue, they believed that their efforts, if successful, could lead to a future of boundless potential for the two countries.

Singh provided leadership on the Indian side, holding 68 meetings with Lambah. Pranab Mukherjee was consistently informed and supportive of the idea, and Lambah also briefed Sonia Gandhi, Vajpayee, Advani, cabinet minister Jaswant Singh, and Brajesh Mishra. Mishra’s suggestions on joint mechanisms were included in the discussions. All top leaders of Jammu and Kashmir, including Omar Abdullah, Farooq Abdullah, Mufti Mohammed Sayeed, and Ghulam Nabi Azad, were kept informed.

The Dangerous Whispers of the Future

Given the current direction of Indian politics since 2019, reviving such hope seems like a distant dream. For those inclined to pursue a new approach, Lambah offers some advice: they can start afresh with new guidelines and parameters but with the same objective of seeking lasting peace between the two neighbours. He warns that while India can defend itself against hostility, ignoring a neighbour with strong antagonism, a growing nuclear weapon arsenal, and worsening stability is an unwise choice. What remains unspoken is that Modi’s policy choice regarding Pakistan is dangerous.

Lambah suggests that the agreement reached through the backchannel negotiations could be revived. Nevertheless, after the constitutional changes of August 5, 2019, which emphasised India’s claims to territories under Pakistani and Chinese control, it seems highly improbable.

The book highlights the contradictions between Lambah as a realist in Pakistan and Lambah as a relentless diplomat striving to fulfil the aspirations of optimistic prime ministers. The question remains whether Lambah’s analytical perspective emerged prominently during his interactions with the prime ministers.

Lambah hailed from a prominent and affluent family in Peshawar, which granted him close connections with influential individuals in Pakistan, particularly from Punjab and Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa province. These personal acquaintances, including figures like Benazir Bhutto, provided him access to influential circles within Pakistan’s social and political fabric.

Lambah maintained a close relationship with Nawaz Sharif, who served as Pakistan’s Prime Minister three times. Their ties dated back to the time before Sharif became Chief Minister of (West) Punjab under Gen Zia-ul-Haq. However, even Sharif distanced himself in the immediate aftermath of the demolition of the Babri Masjid in Ayodhya on December 6, 1992.

While such connections proved valuable in managing situations and conveying Indian perspectives on bilateral matters, their diplomatic value diminished when it truly mattered. For instance, Lambah recounts the lack of response from Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif and Interior Minister Shujat Hussain, both of whom he knew well when he attempted to reach out during the attack on the Indian consul general’s residence in Karachi in December 1992.

Lambah nostalgically recalls the warm reception received by those familiar with his and his wife’s family in Pakistan, adding an engaging narrative element. However, these personal anecdotes hold limited significance in the realm of interstate relations.

Lambah acknowledges the evolution and orientation of the Pakistani state, particularly its military. He observes, “While Pakistan continues to derive the rationale for its existence from Islam, it has sustained itself by creating the spectre of an Indian threat.” Lambah emerged as the preferred diplomat to transform manipulated desires into reality.

The book provides concise accounts of these efforts, including the establishment of a Joint Commission aimed at fostering cooperative ties. However, it becomes evident that these endeavours were calculated manoeuvres.

Although Lambah’s book mentions his 68 meetings with Manmohan Singh and 27 meetings with his Pakistani counterparts, the specific details of these discussions remain undisclosed. Consequently, it becomes challenging to assess how the two countries would have addressed the intricate issues at hand, including Jammu and Kashmir.

A Dance of Doves and Hawks

Despite Lambah’s limited recognition of India’s shortcomings before 2014, his account of the Babri Masjid demolition serves as a stark reminder that a government rooted in Hindutva ideology, with its diplomats acting as representatives of a de facto Hindu Rashtra, does not fortify India’s position in foreign relations. The Modi government has weakened India’s traditional strengths, particularly in South Asia, replacing the moral high ground of progressive values with a feeble imitation of China’s aggressive Wolf Warrior diplomacy.

Unlike China, India lacks the geopolitical and economic influence to achieve its national objectives through forceful rhetoric. While the government’s statements may appease its internal Hindutva supporters, they do little to enhance India’s standing on the global stage.

Over the years, there have been changes in the individuals involved on both sides of the discussion table. However, due to India’s political mockery, the outcomes consistently turned out to be disheartening, despite several promising beginnings.

The relations between India and Pakistan have been extensively discussed and will continue to be of interest. As someone who has played a role in shaping these ties, the author has specific objectives in mind. They state, “Today, the prospects for dialogue, engagement, and a broader peace process seem more distant than ever before… Throughout my nearly half a century of public service, I have had the privilege of serving in various capacities and assignments in India and abroad. Interestingly, more than half of that service has been involved with matters relating to Pakistan, either directly or indirectly…”

Epilogue

It is important to note that one-sided hope doesn’t survive for long. The author’s experiences with Prime Ministers have shown that past hopes have been shattered, and there is no particular reason to believe that they will be successful in the future. Naturally, the future always remains uncertain.

This book may not captivate everyone unless one has an extraordinary negative interest in Pakistan. However, for those who do, it serves as mere documentation. It’s worth mentioning that, true to the author’s nature as a career diplomat, scandalous details are not revealed. The book adheres to the official position without deviating from the straightforward path.

A few personal anecdotes are shared, such as Indira Gandhi’s enjoyment of caviar and Dev Kanta Baruah’s rude behaviour, adding a touch of personality. It’s also worth mentioning that “a key member of the Kargil Committee has informed me that the report did not blame Gujral for ending R&AW operations.”

This book may not be an enthralling read. It often delves into the realm of dullness, at times resembling bureaucratic language. The majority of its contents are already known, except that they are now conveniently compiled in one place.