The worst period of Kashmir militancy coincided with PV Narasimha Rao’s term as Prime Minister. How he handled the goriest situation ever, its diplomatic fallout and pushed for elections to have a civilian government in 1996 is a long story, which was partly tackled by a recent book, writes Masood Hussain

There was a brief speech by the erstwhile Prime Minister, P V Narasimha Rao, fundamental to the 1996 state assembly elections that broke the last major spell of Delhi’s remote rule over Jammu and Kashmir. The interesting speech was recorded at Ouagadougou, the capital of the African nation, Burkina Faso, where Rao was visiting as the first Prime Minister ever. It was transmitted through a satellite to Doordarshan in Delhi and broadcast.

“In a pre-election gesture, Prime Minister PV Narasimha Rao today offered a political package to Jammu and Kashmir on the basis of the Indira-Sheikh Abdullah accord and said the centre has no objection on the use the title of Wazir-e-Azam for the Chief Minister and Sadar-e-Reyasat for the governor of the state legislature so desired,” Hindustan Times reported from Ouagadougou on November 4, 1995. “Mr Rao assured the people of that Article 370 shall not be abrogated, that a package would be worked out to ensure time bound revival of Kashmir economy and that measures had been taken to ensure peaceful conduct of elections, the dates of which would be announced by the Election Commission.”

The speech, the script was, will be followed by a cabinet meeting in Delhi that will pass the resolution that the government would look into the autonomy issue and, at the same time, the Election Commission will be asked to explore ways and means for holding polls. Everything happened as per the script with one interesting exception that was off the script; KNP Salve and Ghulam Nabi Azad opposed the idea and went to the media with their doubts!

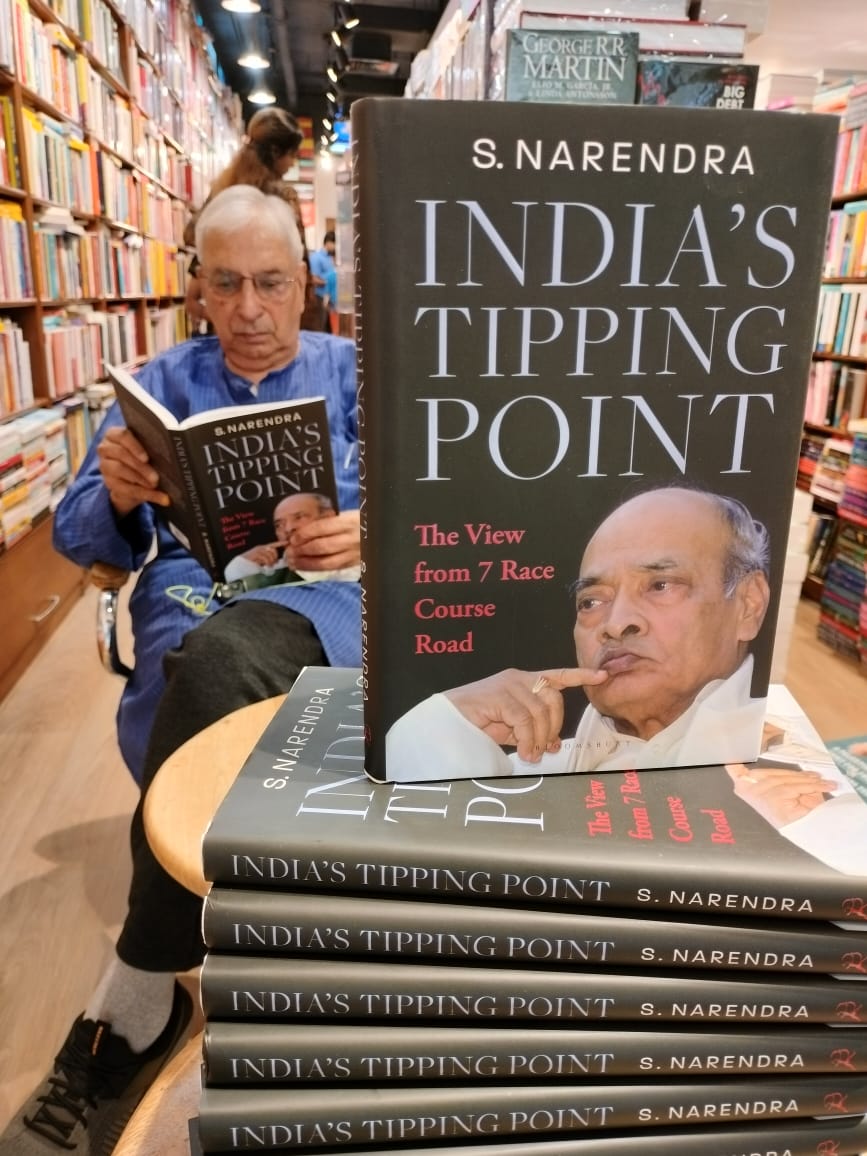

The finer details of this major development have been captured by S Narendra, Rao’s spokesperson and a close aide in his book India’s Tipping Point: The View from 7-Race Course Road that Bloomsbury published earlier this year. Apart from the opposition, even colleagues within Congress were against holding elections. While the BJP was apprehensive that the Congress might do some deal with the Kashmir militants that will turn back the clock, Congressmen men were insisting that the low poll will have adverse global repercussions. Even the then Jammu and Kashmir governor was unhappy over the decision. However, Rao was adamant to hold polls. He believed, “elections will low polling were better than no elections”.

Focus Elections

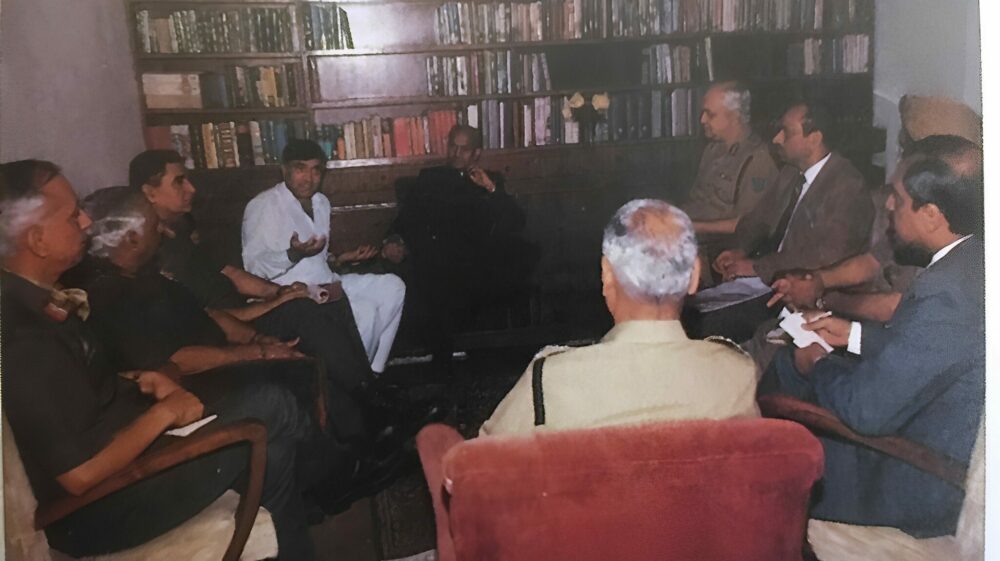

Rao was too engaged with the election idea. He was scheduled to leave for New York on November 2, via Burkina Faso. “On both the day of his departure and the day preceding it, the prime Minister carried on his negotiations with the National Conference and his home minister and Rajesh pilot,” the book has recorded.

Farooq, according to Narendra had set a number of conditions. Abdullah had insisted Roa that “win or lose, he should be the Chief Minister”. In the November 2, early morning meeting, Abdullah had set a condition that the prime minister should make a public statement addressing the people of Jammu and Kashmir about the state’s autonomy under Article 370 of the constitution and make certain promises. This led PMO to get into an instant revisit of the state centre relations and scan every document around. For some reason, the statement could not be made from India, so, it was decided that Rao will speak somewhere and it will be broadcast later.

While the brief speech is known to everybody, Narendra offers interesting details of how it was recorded and sent home. The small African country was ruled by a dictator and was cut off from the rest of the world. It lacked communication facilities. Rao’s plane had to fly to the neighbouring country for refuelling!

“Rao’s broadcast for Doordarshan had to be recorded between 2 and 3 November and transmitted to Delhi through an international satellite,” Narendra, who was the main responsible for the job, has written. “We found out that a communication satellite passed over Burkina Faso once in 24 hours, but for less than one hour!”

The 48 hours that Rao’s team spent at Burkina Faso, Kashmir was the priority. Between diplomatic engagements, Rao would seek and change the draft that he was supposed to record. “About two hours before our departure to New York, we managed to bring the prime minister to his room to record his TV broadcast. Prime Minister Rao chose his words carefully, sticking to the recorded history and announced that the ‘sky was the limit’ for discussing the state’s autonomy within the Indian constitution – that is, short of independence,” Narendra recorded in his book. Everybody was happy as everything went as per the script. “Cars were lined up for departure to the airport when the Doordarshan cameraperson came to me and threw a bombshell. He had forgotten to load a tape into the video camera! The historic broadcast was not on tape!”

It was Surinder Kapoor of ANI, the only other person who had the privilege of recording the speech, who gave the recorded statement that was transmitted to Delhi. However, the goof-up delayed Rao’s departure. “The Prime minister’s broadcast, especially the words ‘the sky’s the limit’, did change the environment,” Narendra wrote.

Key Concerns

By the time, elections took place and Dr Abdullah was sworn in as the Chief Minister on October 9, 1996, Roa had already been replaced by HD Devegowda. Nevertheless, Rao’s efforts towards the establishment of a civilian government in Jammu and Kashmir should not be discounted.

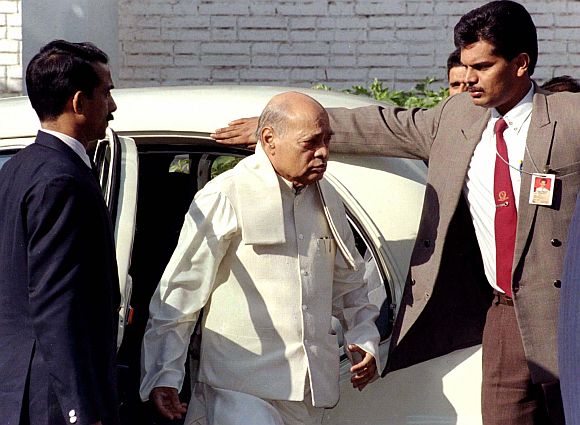

Pamulaparthi Venkata Narasimha Rao (June 28, 1921 – December 23, 2004) was the Prime Minister of India between June 21, 1991, and May 16, 1996. This was the peak of militancy in Jammu and Kashmir. Managing Jammu and Kashmir for this period was a challenging task. All the major events and most of the diplomatic attention that Kashmir attracted took place in this period.

The installation of a civilian government in Jammu and Kashmir was the last major exercise of Rao, the man who is genuinely credited for changing India forever. There have been a number of books written on the statecraft that Rao practised, Narendra’s book offers a crisp and clear idea about his Kashmir policy.

Rao Kashmir’s actions were dictated by a set of concerns, the book reveals. The first concern was a protracted central rule of the state. His second concern was that the public funds remained underutilised and the people were not getting benefited.

Succumbing to the political class before the militancy was his third concern. Militancy had succeeded in shutting down democratic political activities completely. “The shuttered offices of the main political parties cleared the way for the rise of hitherto unheard-of persons to fill the vacuum,” Narendra has written. He had tried to revive Congress but under GR Kar’s leadership, it did not wish to throw its hat in the ring, “When I gave this feedback to the prime minister, he told me that he had sounded out Ghulam Nabi Azad, who was serving as a central minister to take up the state party leadership, but he was reluctant.”

The campaign by Pakistan and militants to create an international perception that the conflict could spiral into a bilateral war with Pakistan was his fourth concern, according to the book. “International opinion was being mobilised by the militants’ propaganda that the Indian army engaged in repressive actions and violated human rights,” Narendra wrote.

Counter Measures

The book details how these concerns led Rao to adopt a brick-by-brick approach to rebuild a robust counter-mechanism.

Feeling the Kashmir heat, Rao enforced a cabinet reshuffle in early 1993, in which he created the Department of Kashmir Affairs, moved it to PMO and got his “trusted pro-active colleague”, Rajesh Pilot as the minister of state for home. Soon, he would fly to Srinagar and have meetings with anybody and everybody who wished to have a talk.

A proactive pilot led to tensions in Srinagar Raj Bhawan though and created, what many said, was a “parallel power centre”. Narendra also attributes the replacement of GareshChander Saxena by (General) KV Krishna Rao and the resignation of Madhav Godbole as Home Secretary to the Pilot impact.

At the central level, Rao started giving extra-ordinary importance to Dr Manmohan Singh, his finance minister, who actually led the economic change in India under Rao’s leadership. A lot of Kashmir-related ideas were supposed to be first vetted by Dr Singh and then they could get the ears of the PMO. “In a subtle move, the prime minister was involving Finance Minister Manmohan Singh in the Kashmir affairs discussions,” Narendra has written, “Perhaps this was intended to put before the people of Jammu and Kashmir a credible, non-political face as and when required.”

Interestingly, Dr Singh retained this authority from the day of cobbling the Congress-PDP alliance in 2002 to the championing of a Kashmir solution till the last days of his first term as the PMO.

Media Management

Media played a key role in disseminating information. In the first go, the Rao government wanted to improve the working of media in Jammu and Kashmir. Militants wanted their cause and activities to get visibility and the government banned the local media for giving space to separatist voices.

“Facing this crossfire, many state newspapers chose to shut down,” Narendra, who personally handled the media management project of Jammu and Kashmir has recorded. “Newspapers from outside were airlifted but they could not be distributed widely. It took some effort by the central government officials including me to convince the state government not to pounce on local newspapers when they published news and views favourable to militants, so long as they published news and views of the other side too.”

The author of the book was mandated to fly to Srinagar often to “revive the state media” as the state’s own information department was “ill-equipped to serve the state media.”

That was the time when foreign media was banned from visiting Jammu and Kashmir. While they were prevented to gain first-hand information from the ground, the global media outlets hired local stringers who worked for them.

“As there was no free flow of information and the government news outlets had lost credibility, the people of the valley mostly relied on BBC Radio, whose signals reached the remotest corners,” the book acknowledges the 1990s trend. There were efforts to counter it and everything failed. “The prime minister ensured that the ban on foreign media was lifted. No doubt there was an initial flood of stories adverse to the government, but this changed as the ground situation in the valley improved.”

Civil Liberties

It was the era when human rights were the key issue. It was being talked about almost everywhere within Kashmir, in Delhi and offshore. Offering an inside view, Narendra has written that while “some cases of human rights abuses by the security personnel” were “exaggerated”, the atrocities committed by the militants were ignored by the foreign human rights advocates. “Amnesty International had become the sole agency to voice the people’s grievances about human rights abuses,” the book has recorded As the security grid was unwilling to deal with the cases of human rights abuses transparently fearing it will demoralise the forces, “India found itself on the wrong end of the stick”.

It was against this backdrop that Rao while attending reforms in the criminal justice system talked about human rights within the framework of democracy and the constitution. It led to the constitution of the National Human Rights Commission (NHRC). “Once the NHRC began functioning, the separatists could no longer shoot from Amnesty International’s shoulder,” Narendra wrote. “Slowly, the NHRC managed to persuade the security forces to sensitise their personnel about the need to respect human rights while dealing with civil conflict.”

The issue of human rights, however, was not limited to India, the Kashmir case was already global. Pakistan had managed to move a resolution on human rights that was likely to be supported by many countries. Had the resolution been adopted, it would have been a serious diplomatic failure for India.

Kashmir Diplomacy

“Rao adroitly sent a powerful delegation under the opposition leader Atal Bihari Vajpayee to argue India’s case opposing this resolution,” the book has recorded. The delegation included Salman Khursheed and Dr Farooq Abdullah. “The Vajpayee-led delegation succeeded in persuading the UN body not to take up the Pakistan resolution.” The book, however, has skipped offering details about how this Himalayan diplomatic battle was won with the help of Iran.

This diplomatic victory was preceded by the Rao government undoing the “wooden-headed” ban on diplomats from flying to Jammu and Kashmir in 1994. “His reasoning was that the ground situation in the valley had changed, and diplomats should be facilitated to assess the situation for themselves and report back to their governments,” Narendra has recorded. “This deft diplomatic measure changed the perception of foreign governments who had fallen prey to Pakistan’s propaganda.”

Rao government was literally scared of what various American diplomats including Assistant Secretary Robin Raphel were doing and talking within and outside Kashmir. In fact, when Rao was busy talking to Dr Farooq about his party’s participation in elections and the possible political package, Raphel reiterated the disputed status of Kashmir. It was against this backdrop that India permitted a top US diplomat – Frank G Wisner, who was US ambassador to India between June 9, 1994, and July 12, 1997 – to fly to Srinagar and assess the situation. His assessment was key to the early polls and changed American diplomacy on Kashmir. The book acknowledges that development: “Once diplomats from the US undertook a visit to Jammu and Kashmir and returned convinced that the people of the valley were fed up with militancy and were ready to elect their own state government, there was a remarkable change in the news reporting about the valley, especially by the US media.”

This, the Rao government did without preventing the frequent interactions between the Kashmir separatist leaders and the Pakistan diplomats and politicians in Delhi. Though the issue was flagged to him, he played it down. “His typical reaction was – ‘let them, so what?” the book says. “Such level-headedness helped to cool things and expanded dialogues and trialogues.” At one point in time, he did not prevent the participation of a group of alleged Hurriyat men to fly Geneva. Later, he flew a group of OIC diplomats to Srinagar.

A Resolution

It was in anticipation of the Pakistan resolution in the UN body on February 27, 1994, that Rao started countering it differently. “Rao encouraged the opposition to bring up a Lok Sabha resolution – passed unanimously later – that India should make efforts to reclaim Pakistan-occupied Kashmir,” Narendra has written.

February 22, 1994, the 4-point resolution is a vital document that everybody has been talking about since then. Even the BJP has been insisting that it is duty-bound to implement it. The resolution reads: “(a) The State of Jammu and Kashmir has been, is and shall be an integral part of India and any attempts to separate it from the rest of the country will be resisted by all necessary means; (b) India has the will and capacity to firmly counter all designs against its unity, sovereignty and territorial integrity; and demands that (c) Pakistan must vacate the areas of the Indian State of Jammu and Kashmir, which they have occupied through aggression; and resolves that (d) All attempts to interfere in the internal affairs of India will be met resolutely.”

The resolution is also being seen as a counter to the resolution that Pakistan Parliament adopted on February 9, 1990, rejecting Jammu and Kashmir’s accession to India and even demanding UN resolution for it. It also came against of backdrop of a perception that some world powers were attempting an “international coup” in Kashmir.

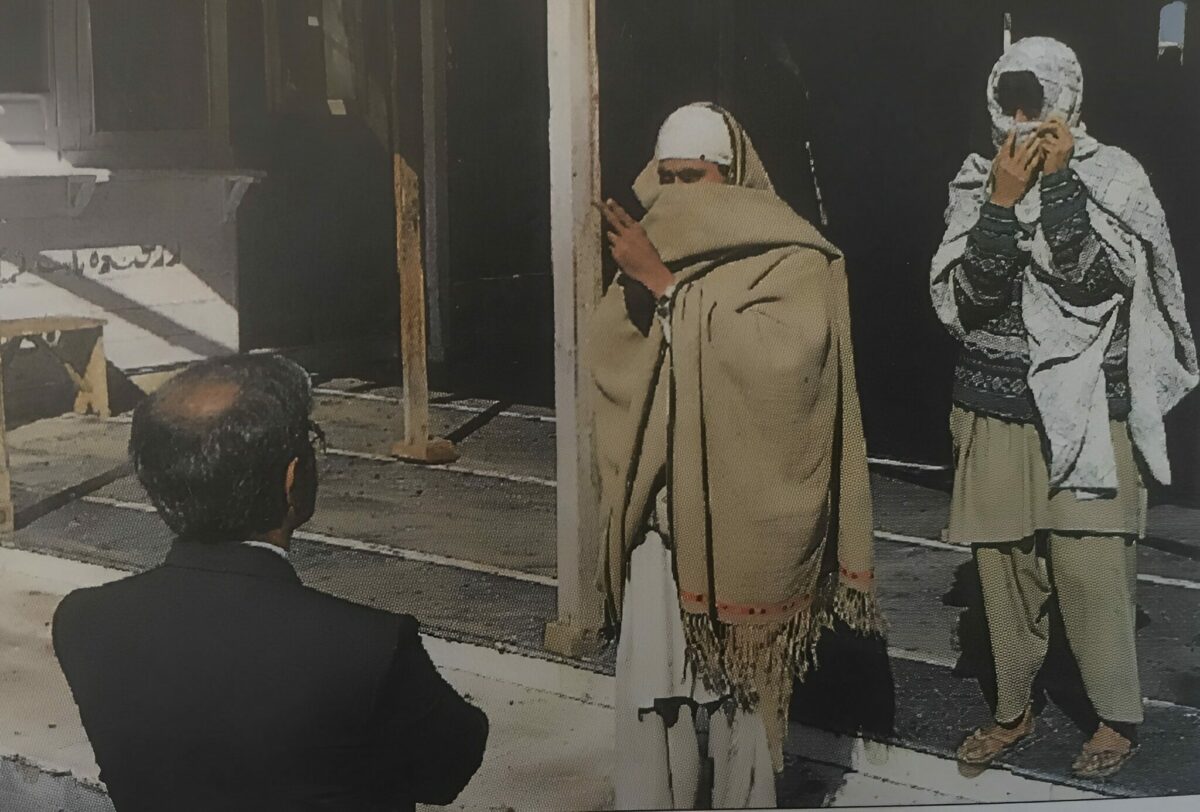

Hazratbal, Chrar

However, Rao’s chessboard statecraft could not prevent major mishaps like the 32-day siege of Hazratbal between October 14 to November 16, 1993, and the destruction of the Chrar-e-Sharief township after a protracted standoff between the security grid and the militants, mostly non-natives Pakistanis, on May 11, 1995. All the holed-up militants in the Dargah Hazratbal were given safe passage as part of the negotiations between the government and the militants.

“The aim was to draw the government forces into a fight, claim that they had attacked a holy shrine of the Muslims and inflame communal passions,” the book suggests. “With great patience, the government managed to negotiate a peaceful end to this siege.”

That, however, was not the case in Chrar-e-Sharief, the home to the shrine of Kashmir’s most respected standard-bearer saint, Sheikh Nooruddin Noorani. The entire township went into flames on the eve of Eid forcing a curfew on the entire Kashmir. While the residents and the militants accused the army of the destruction, the government and the security grid held the fugitives responsible.

Perhaps one of the major setbacks to the Rao government, Narendra has offered a detailed inside view of the crisis: “The terrorists had managed to enter the shrine mainly because of intelligence failure by the state government and the intelligence agencies. Once they were inside the shrine, located in a population area, flushing out the terrorists with military action was fraught with risks f heavy civilian casualties. The occupants were iconoclastic Sunni Muslims who had no respect for Sufi icons. Therefore, the government’s utmost concern was to save the shrine from destruction, which could be blamed on the Indian forces. In meeting after meeting of the political affairs committee that included the home, finance, defence and HRD ministers, the consensus was to avoid provoking the terrorists. The border Security Force (BSF) deployed around the shrine had specific instructions to surround the outer periphery, but not move in without specific government orders. Between the security committee and the intelligence committee, Army and BSF representatives, the consensus was not to give cause for the terrorists inside the shrine to blow up the place. Governor Krishna Rao was authorised to negotiate a peaceful end to the siege. Krishna Rao more than once publicly declared the government’s willingness to grant the terrorists safe passage to the Pakistan border, but this did not receive a positive response.”

The standoff continued for more than two months and eventually, the town went up in flames. It was a major crisis. The twin houses of the parliament discussed and debated the tragedy in protracted debates and Prime Minister spoke to both houses.

“I am glad that I am able to see some light at the end of the tunnel. What they meant by Azadi may not mean total independence,” Rao famously told the Rajya Sabha on May 16, 1995. “It may mean something less. It may be something which we may not reject, hopefully. But I am not sure of anything at the moment. That is why the dialogue is on.”

Rao Details

During the years of Rao’s Kashmir rule, countless incidents including the goriest incidents and a series of blazes devastated Kashmir. Understanding the Roa regime in the Kashmir context requires a lot of scholarship as it involved almost everything from street fighting to sophisticated diplomatic wars. There have been many books on this era but not many have enough details to be authoritative.

Vinay Sitapati’s 2018 book The Man Who Remade India: A Biography of PV Narsimha Rao does offer some details about Kashmir. Apart from offering details about how Rao successfully used Iran to get India to manage the impact of the Babri Masjid demolition and the UNHRC resolution on Kashmir, the book has many interesting details. It was Rao who prevented the final settlement of the Siachen glacier issue with Pakistan in 1992. “His private papers are full of secret meetings he held with terrorists and freedom fighters of varying shades, imploring them to stand for elections instead,” the book reveals.